By Emil Jeyaratnam and Wes Mountain, The Conversation

Alcohol is a depressant, a diuretic, and a disinfectant. These generally aren’t pleasant attributes, but people have been drinking alcohol for thousands of years – some of the earliest written texts mention or contain recipes for beer, and pottery shards from China show people may have been making alcohol as far back as 7,000BCE.

So what is this special chemical that we’ve loved to drink for so long?

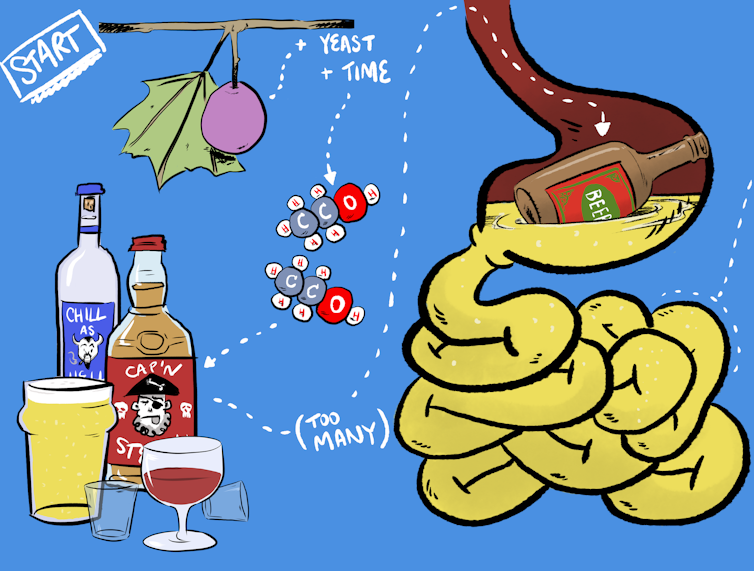

Well, there are many types of alcoholic drinks – fizzy and flat, hot and cold, fermented and distilled – but all of the alcohol we drink as humans is ethanol based.

The process of how ethanol gets from the glass into your brain is not straight forward. And how quickly it gets to your brain (and whether or not it’s quickly broken down by your liver) is down to a variety of factors, one of which it’s actually very easy for us to control: whether or not we’ve eaten.

Let’s take a look at what happens after that first sip of alcohol.

The organ that takes on the biggest burden of processing ethanol in our body is the liver.

The liver is one of our largest and most important organs and it performs hundreds of functions, including converting the nutrients in food into something our bodies can actually use.

But there’s a reason we apologise to our livers if we’ve a big night: the liver’s other job is processing any toxic substances we ingest into something harmless, or removing them from the body altogether. Which makes it the perfect organ to deal with ethanol.

Most – about 90 to 98% – of the ethanol we consume is processed in the liver, with the remainder either removed in our urine, sweat or when we exhale.

The liver processes alcohol in two distinct steps. The first involves an enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), which breaks down ethanol into a chemical called acetaldehyde. Unfortunately acetaldehyde is actually a toxin, which is why there’s a second stage to the process.

Another enzyme – aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) – quickly breaks down acetaldehyde into acetate, which is harmless. It’s then either excreted, used to make other molecules or broken down into water and carbon dioxide.

And it’s while your liver is slowly processing the ethanol in your system (as quickly as it can) that the remainder makes its way to your brain.

A complicating factor for determining how drunk we’re likely to feel after a certain amount of alcohol is that different people will process alcohol at different speeds.

There are many things that impact how quickly the body processes alcohol, including your weight, body composition and hormones, the number of drinks you’ve had and how quickly you drank them.

But roughly, the liver can effectively process about 1 standard drink in an hour, give or take. Women and men do process alcohol at different speeds, which is why alcohol campaigns often suggest women consume fewer drinks in the first hour than men.

The problems start when you consume more than a standard drink per hour – which is not hard to do, given an average bottle of beer has 1.2 to 1.4 standard drinks, and a restaurant sized glass of wine is about 1.5 standard drinks.

While it can be hard to match up exactly how many drinks equate to how intoxicated you’ll feel, your blood alcohol concentration (or BAC) gives a pretty good indication of what most people will feel as they ingest escalating amounts of alcohol.

So what does that actually look like?

Alcohol makes us feel increasing pleasure and relaxation as we drink more, while simultaneously hampering both our ability to make decisions and even move capably, which can lead to dangerous consequences.

The actual recommended intake for adults is just two standard drinks a day, which is less than a pint of beer. Realistically, many Australians often drink more than this. So the important thing is to be aware of your limits, plan for how much you intend to drink, eat a meal before you begin drinking, and drink responsibly.

Read more:

There are four types of drinker – which one are you?

Emil Jeyaratnam, Multimedia Editor, The Conversation and Wes Mountain, Deputy Multimedia Editor, The Conversation

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.