Stateline

Over the past three decades, the world has seen a steady decline in the number of women dying from childbirth. There’s been a notable outlier: the United States.

Here the maternal mortality rate has been climbing, putting the United States in the unenviable company of Afghanistan, Lesotho and Swaziland as countries with rising rates.

But that trend has been reversed in dramatic fashion in one state: California. The state Department of Public Health calculates that between 2006 and 2013, California lowered its maternal mortality rate by 55 percent from 16.9 to 7.3 deaths for every 100,000 live births, which translates to saving about one life in every 10,000 live births. The California rate is in line with those in Western Europe. During that same period, according to federal data, the U.S. rate rose from 13.3 to 22.

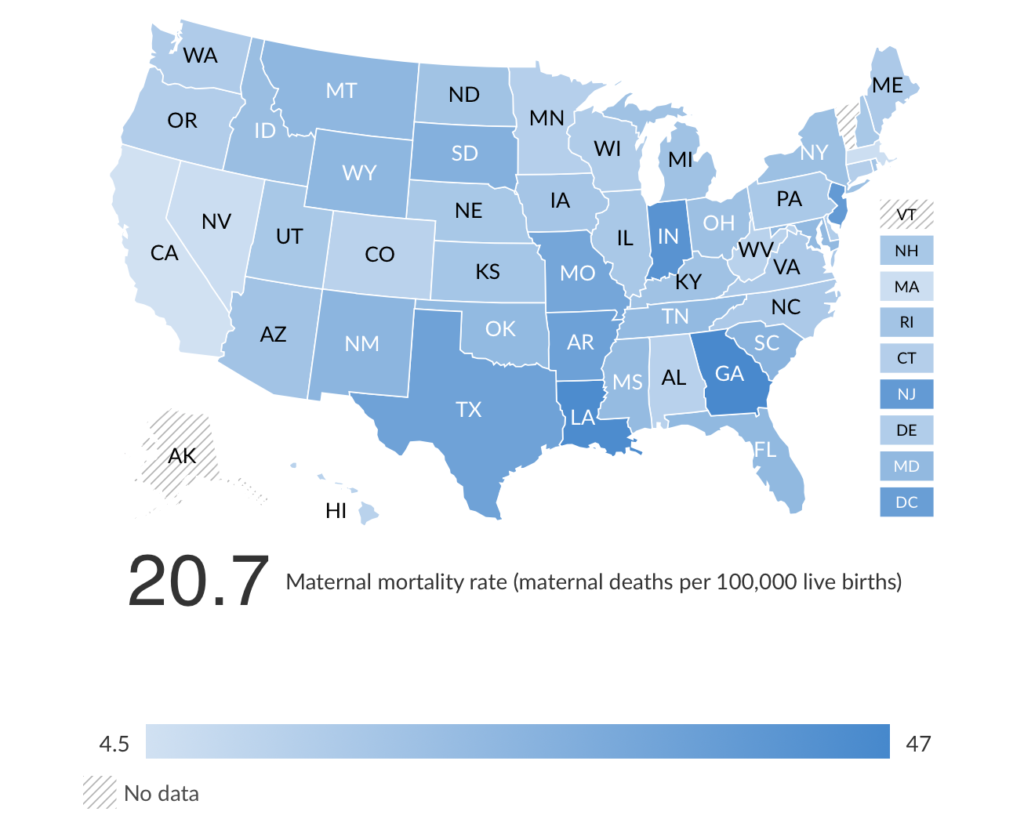

The United Health Foundation, which ranks states according to various health indices, using primarily a five-year average of federal data from 2011 to 2015, put the U.S. maternal mortality rate at 20.7 per 100,000 live births and California’s at 4.5.

Experts in maternal health blame the high U.S. rate on poverty, untreated chronic conditions and a lack of access to health care, especially in rural areas where hospitals and maternity units have closed in the past few years. But California has made a difference in part by focusing narrowly on problems that arise during labor and delivery, using data collection to quickly identify deficiencies (such as failing to have the right supplies on hand or performing unnecessary C-sections) and training nurses and doctors to overcome them.

Those involved in California’s efforts acknowledge they can’t definitively say how much the state’s falling maternal mortality rate is the result of its efforts. The state has long provided maternity care for poor women and also embraced the Affordable Care Act, which provided health insurance to more women. But other blue states that eagerly implemented ACA provisions did not experience reversals as dramatic as in the Golden State.

The rest of the country has been paying attention.

“There’s no excuse now,” said Stephanie Teleki, who leads maternity care initiatives at the California Health Care Foundation, a philanthropic nonprofit that has funded some of the California efforts. “There are free [instruction manuals] to help hospitals address the major drivers of maternal mortality and morbidity. And we have a data center in California that can be replicated in other states that is low-burden and low-cost to hospitals.

“This isn’t some weird California thing that can’t be replicated,” Teleki said. “This is doable in other states. It’s a matter of having the will and the funding to get it off the ground.” The cost to the state Department of Public Health is about $950,000 a year with additional resources from grants and foundations.

Detailed Manuals

The California effort began around 2006, when officials at the state Department of Public Health first noticed the rising rates of maternal deaths. “It was disturbing, and frankly we didn’t know why,” said Connie Mitchell, deputy director of the department’s Center for Family Health.

The department created a pregnancy-related mortality review board to dig into causes of every death. (As of last year, 29 other states had created similar boards, according to the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program, a national coalition with expertise in maternal health.) With Stanford, the agency also created the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, which brought together clinicians, hospitals and other maternity experts to sift through the data to identify solutions.

In turn, the state and the collaborative created exhaustive “how to” manuals for hospitals and clinicians, detailing the best practices to address specific circumstances, such as obstetric hemorrhages and pre-eclampsia, a pregnancy-related complication characterized by high blood pressure and signs of damage to an organ, usually the liver or kidneys. They also sent experts to train doctors and nurses on the techniques.

The first manual, distributed in 2010, addressed hemorrhages. “Early on, we discovered that labor and delivery was often not ready to spring into action when a hemorrhage happened,” Mitchell said. “They hadn’t drilled for it in the delivery room, or they kept blood supplies in another part of the hospital and a nurse had to run around for 15 minutes to get it.”

The hemorrhage toolkit, for example, details what to do when a woman experiences excessive bleeding in the delivery room, who should perform which procedures and what supplies should be on hand. There’s more: It recommends stocking a hemorrhage-specific tray of medicines in the labor and delivery refrigerator, and advises that hospitals put together a “hemorrhage cart” on wheels, holding everything from uterine forceps and sutures to a bright task light.

Since then, the collaborative has created guides on cardiovascular disease, pre-eclampsia and venous thrombosis, a blood clot in a vein that is a common cause of pregnancy-related deaths. The collaborative also has distributed instructions for reducing the rate of Caesarean deliveries, which are riskier for women than vaginal births. All are freely available to hospitals and practitioners outside California.

Kathleen Belzer, president of the California Nurse-Midwives Association, said the instruction manuals are ubiquitous in hospital maternity units and birthing centers.

“I think every [obstetrical care] provider in California and most hospital systems absolutely use the [instruction manuals],” she said. “They are very well embraced.”

The heart of the system, though, is a fast-moving, comprehensive system called the Maternal Data Center; it collects data from birth records, hospital discharge records and other medical information supplied by the state’s hospitals. Researchers analyze data at a statewide, regional and even hospital level to determine whether providers are following the best practices.

The system allows hospitals to check their performance against peers and can pinpoint problems with individual practitioners. Is a doctor’s C-section rate high? Is it because that doctor has a high rate of labor inductions?

Hospitals send the data to the Maternal Data Center every 45 days, which, in the world of hospital data collection, is unusually fast and allows for quick interventions when a problem is identified.

The California collaborative said it recently started to cooperate with Oregon (13.7 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births) and Washington (14.8), to help those states create their own data systems.

Other states have also taken actions similar to California’s. Florida, Massachusetts and Ohio have adopted measures to enable the sharing of birth certificates and hospital discharge records to provide a deeper level of analyses to identify areas for improvement.

At least 40 states have also established central bodies like California’s collaborative, to provide expert support and training to hospitals and practitioners. And North Carolina created a program to identify low-income pregnant women in order to provide them with coordinated care that addresses not just their medical needs but also help with nutrition, housing and transportation.

No other state, though, has developed as thorough a system for improvements as has California.

‘Passionate About the Work’

California’s plan brings together all the players in maternal health: clinicians, hospitals, state agencies including Medi-Cal, the administrator of Medicaid in California, professional medical associations, commercial insurance carriers, and philanthropic organizations.

“It’s been the work of a lot of people who are very engaged and passionate about the work,” said Cathie Markow, administrative director of the collaborative.

According to the collaborative, 212 of the state’s 240 hospitals, representing more than 95 percent of births, submit data to the Maternal Data Center. Several Medicaid-managed care plans in the state require hospitals to participate, according to Markow.

Inspired by California’s efforts, in 2014, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Nurse-Midwives, and the American Hospital Association created the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health to provide support and guidance to states. Nineteen states, including Florida, Illinois, New York and Texas, are now working with the coalition, known as AIM.

“We all look to California because they have reversed the trend and decreased their maternal mortality rate significantly,” said Dr. Lisa Hollier, a Houston OB-GYN and president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The alliance promotes many of the methods pioneered in California, including the creation of collaboratives on maternity care, use of instruction manuals and rapid data collection and analysis.

But even cheerleaders for the California effort agree that there are limits to the success.

While the maternal mortality rate has declined overall in California across all demographic groups, African-American woman still are three to four times more likely to die from complications from pregnancy than are white women. In 2006, black women were more than five times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications.

The collaborative now is gathering data to focus on closing that racial disparity.

As Teleki, of the California Health Care Foundation, said, the state is pointing the way for the rest of the nation.

“This can be replicated in other states and indeed must be replicated in other states because these numbers we’re seeing are despicable,” she said. “We like to think we have great health care available in this country, but maternal mortality is one of the major indicators of a country’s health, and in some states there are third-world levels of deaths associated with pregnancy.”

Stateline is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of the Pew Center on the States that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.