Stateline

A woman with diabetes holds her prescriptions in her Sandy, Utah, home. She has had to change health insurance plans three years in a row. Twice, new insurers wouldn’t cover the medicine she’d been taking to control her blood sugar, instead requiring her to use an inexpensive alternative that she knew didn’t work for her.

Frustrated by federal inaction, state lawmakers in 41 states have proposed detailed plans to lower soaring prescription drug costs. Some measures would give state Medicaid agencies more negotiating power. Others would disclose the pricing decisions of the drug manufacturers and the companies that administer prescription drug plans.

The more ambitious proposals would bump up against federal authority, such as legislation that would allow importing drugs from Canada or alter federal statutes on the prices states pay for drugs in Medicaid. They likely would have to survive a challenge in federal court. And many likely would face resistance from a deep-pocketed pharmaceutical industry.

According to the National Institute on Money and Politics, a nonprofit that collects campaign finance data, the pharmaceutical industry in 2018 contributed nearly $19 million to state campaigns, and $56 million to federal ones.

“States are limited in power in this area,” said Rachel Sachs, a health law expert at Washington University in St. Louis School of Law. “But one of the impacts of these efforts is to put pressure on the federal government, and force it to justify its actions to stymie the states.”

President Donald Trump has criticized soaring drug prices, and on Thursday the Department of Health and Human Services announced a draft regulation that would allow drugmakers to offer discounted prices directly to consumers – but without giving rebates to Medicaid managed care organizations or the middlemen known as pharmacy benefit managers.

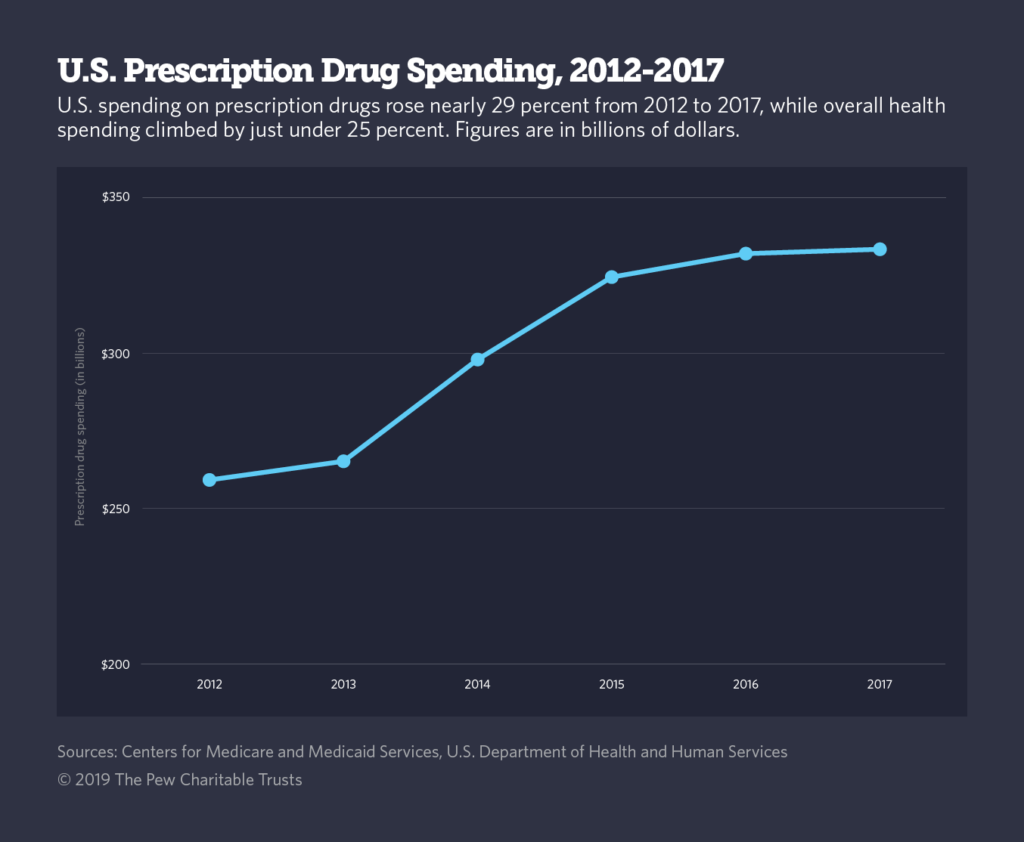

Between 2012 and 2017, drug spending in the United States increased nearly 29 percent while overall health spending rose less than 25 percent. Since 2013, the growth in prescription drug spending has exceeded GDP growth, which means the industry is consuming an increasingly large share of the U.S. economy.

Just this week, committees in both houses of Congress held hearings to consider how to arrest the trend.

In his opening statement, U.S. House Oversight Committee Chairman Elijah Cummings, a Maryland Democrat, praised what he said is a bipartisan consensus that drug companies’ aggressive price hikes need to be reined in.

“We have seen time after time that drug companies make money hand over fist by raising the prices of their drugs — often without justification, and sometimes overnight — while patients are left holding the bill,” Cummings said in his statement, adding later: “We have a duty to act now.”

On the other side of Capitol Hill, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the self-described “center-right” American Action Forum, told the Republican-led Senate Finance Committee that government policies were at least partly to blame for rising drug prices.

Holtz-Eakin cited laws governing Medicaid payments to drug companies and the Affordable Care Act’s tax increases on manufacturers and importers.

“It should not be surprising,” he said, that drug prices increased simultaneously with the passage of the ACA.

Priscilla VanderVeer, a spokeswoman for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the lobbying arm of the industry, said PhRMA, as the group is known, would oppose many of the state bills.

The proposals wouldn’t lower prices on medications, she said, and would discourage corporate investment in research and development of new drugs.

“We absolutely understand where patients are coming from, and their struggles to get the medications they need at an affordable price,” VanderVeer said. “But let’s focus on the entire chain, not just manufacturers.”

It isn’t the case, though, that lawmakers are focusing only on manufacturers; a few bills offered this session would force actions either from insurers or pharmacy benefit managers, the companies that administer drug plans. Other proposals would study foreign drug importation or encourage price negotiations to benefit, say, Medicaid patients.

Federal Prerogatives

The federal government has zealously guarded its authority over drug pricing.

Last year, for example, the Trump administration rejected Massachusetts’ request to become the first state to exclude certain drugs from its Medicaid program, to extract better prices from pharmaceutical companies.

By law, all state Medicaid agencies must carry every drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, in return for set rebates from drugmakers.

Massachusetts proposed to offer at least one medicine in every “therapeutic class,” that is, treatments intended to address a specific condition or illness, such as blood clots or angina.

It also sought the authority to evaluate the effectiveness of newly introduced drugs, by comparing them with other medicines in the same class.

That idea worries some health analysts, who note that even within the same therapeutic class, one medication may work better than another for an individual patient. Some organizations that represent people with certain diseases joined drug manufacturers in objecting to Massachusetts’ proposal.

The Trump administration also opposes states importing cheaper drugs from Canada.

Last year, Vermont became the first state to pursue importation. Vermont’s measure would save the commercial insurance industry between $1 million and $5 million a year, a state report estimated. Lawmakers in Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, Oregon and Virginia have proposed studies of the idea.

But buying drugs from Canada requires federal approval, which, until recently, seemed unlikely. U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar last spring said several times he had no interest in allowing Vermont or other states to proceed with such a plan.

But in response to some dramatic increases in drug prices, he softened his position, at least in the case of some generic medications produced by a single manufacturer. He said last summer that he was setting up a working group to study importing drugs from abroad.

Maryland’s attempt to control drug prices ran aground last year in a federal courtroom. The 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in April threw out a 2017 Maryland law enacted to curb “unwarranted” price hikes, saying the state had no authority to regulate interstate commerce.

Knowing that states are on shaky ground, some drug companies have pushed back against attempts to limit their prices.

They did so in New York, where lawmakers in 2017 enacted a requirement that makers of certain high-priced drugs give the state’s Medicaid agency discounts beyond those set by federal statute.

Vertex, the manufacturer of a cystic fibrosis medication with a retail price of $272,000 a year, refused. And New York was forced to acknowledge it could not require compliance.

In a message to Stateline, Vertex touted the efficacy of its cystic fibrosis drug. “The price of our medicines reflect the significant value they bring to patients,” said Sarah D’Souza, a Vertex spokeswoman, adding, “We do not believe an additional rebate is warranted.”

Still, other states see promise in that approach. Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, recently proposed a measure that would enable the state Medicaid agency to negotiate further discounts on certain drugs.

If negotiations don’t work, the state could subject the manufacturer to a public rate-setting process, require more transparency on pricing, or refer the matter to the state’s attorney general’s office for possible prosecution under consumer protection laws. Legislators in Connecticut and Maryland are pushing similar proposals.

State lawmakers in Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York and Virginia also want to prevent drugmakers from enacting steep year-to-year price increases in the commercial market.

Under the Minnesota proposal, for example, manufacturers of generic medications would be referred to the state attorney general if they increased the wholesale price of a medication by 50 percent or more. Legislation in the other states also would set limits.

Linda Gorman, director of the Health Care Policy Center, at the Independence Institute, a libertarian think tank based in Denver, said interfering in the market is a bad idea.

“It’s a waste of time, and you’ll only end up with more regulation and higher overall prices,” Gorman said. She argues, for example, that by requiring drugmakers to give discounts to Medicaid agencies, the federal government drives up drug prices in commercial plans.

No Approval Required

Mindful of recent setbacks, some governors and lawmakers are exploring ideas that wouldn’t require federal approval.

In California, Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom in January signed an executive order directing all Medicaid managed-care organizations to collectively negotiate drug prices on behalf of the state’s 13 million Medicaid beneficiaries. Combined, the groups would be the largest direct purchaser of prescription drugs in the country.

“We will use our market power and moral power to demand fairer prices for prescription drugs,” Newsom said in his inauguration speech.

“We’d all love to see this being done on the federal level, but we’re not expecting that.” — Vincent DeMarco, president Maryland Health Care for All Coalition

Other states are emphasizing transparency, with the goal of shaming drug companies into moderating their prices. New Hampshire, New Jersey and Washington state are considering requiring manufacturers to disclose to states (but usually not to the public, to protect proprietary information) what they spend on advertising, and research and development.

Still others, including Arizona, Florida, Maine, New Jersey and New York, also want to cast light on the operations of pharmacy benefit managers, known as PBMs, the giant buying networks that administer prescription plans on behalf of insurers.

The theory behind PBMs is that their size and expertise results in savings for consumers. In recent years, however, critics have argued that the PBMs are pocketing the savings rather than passing them on to consumers. And in many states, the pharmacy benefit managers impose a gag order on pharmacists, blocking them from telling consumers about cheaper drug options.

Other state legislators want to regulate PBMs. Legislators in Delaware, Minnesota and South Carolina have filed bills that would require PBMs to be licensed, so that the state could standardize their practices. While some states require PBMs to register with the state, only a few, such as Georgia and South Dakota, have licensing requirements.

Lawmakers in Delaware, New Jersey, Texas and Virginia also want to end the practice of “clawbacks,” in which PBMs and insurance carriers pocket the difference between the total cost of a prescription drug and a patient’s copayment. Legislators in New Jersey, Oklahoma, Texas and Virginia also want to make it illegal for PBMs to prevent pharmacies from disclosing cheaper alternatives to customers.

In a rare show of bipartisanship in Washington, President Donald Trump signed a bill in October that prohibits PBMs from including gag orders in their contracts with pharmacies. State legislators with anti-gagging bills want to make sure state regulators can also enforce the prohibition.

This week’s hearings on Capitol Hill may presage federal action on prescription drug prices, but many state-level decision-makers are inclined to go ahead without Washington.

“We’d all love to see this being done on the federal level, but we’re not expecting that,” said Vincent DeMarco, president of Maryland Health Care for All Coalition.

“People can’t afford drug prices now; we can’t wait any longer to do something about that.”

Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.