Researchers at the University of Washington have identified a mutation that appears to be the cause of a rare form of brain aneurysm and could be treated with a drug already approved for cancer therapy.

The finding suggests that other, more common, forms of aneurysms may also be caused by yet undiscovered mutations that could be treated with medication instead of high-risk surgical interventions.

The study was reported in the American Journal of Human Genetics.

“Right now, we are largely limited to surgical procedures such as craniotomy to clip or repair aneurysms or on endovascular treatments to place stents and coils,” said Dr. Manuel Ferreira, UW Medicine’s chief of neurological surgery, who led the research project. “Our findings suggest that medications, in this case the well-tolerated cancer drug sunitinib, may be able to treat some of these aneurysms.”

Aneurysms occur when the blood vessel wall weakens. These weakened vessel walls bulge and often burst. Some ruptures result in catastrophic bleeding, particularly when they are located in the brain.

A few aneurysms are caused by inherited genetic disorders, said Ferreira, but these disorders are relatively rare. In most cases, the cause of an aneurysm is unknown. Such sporadic aneurysms have been thought to result from smoking, high blood pressure or other factors that damage to the vessel wall.

“Our study is the first to identify a genetic cause for a sporadic aneurysm,” Ferreira said. “I suspect we’ll find other types of aneurysms have a genetic cause as well.”

In the study, researchers began with the case of a young man who started to develop aneurysms at an early age. Genetic evaluations at major medical centers around the country had failed to find mutations typical of the inherited disorders associated with aneurysm.

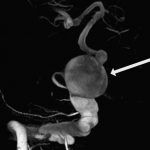

The type of aneurysm this patient developed are called fusiform, which means or spindle-shaped, because they tend to be wide in the middle and taper at the ends. These are unlike the much more common form of aneurysms, saccular aneurysms, which form spherical, balloon-like bulges on the side of the blood vessel.

Curiously, the man’s aneurysms appeared only on the right side of his brain. He also had discolored and abnormally stretchy skin patches… These also tended to be on the right side of his body. His right arm and fingers were also abnormally long. The left side of his body was almost entirely unaffected.

Ferreira wondered whether the patient’s aneurysms were caused by mosaicism. In this condition, instead of inheriting a mutation from a parent, in which case every cell in the body will carry the mutation, the mutation occurs during embryonic development.

When this happens, tissues derived from the embryonic cell with the acquired mutation tend to exhibit the disorder and those tissues that did not tend to be normal. Mosaicism would explain why his patient had the aneurysms and the skin and limb abnormalities on one side.

To test this hypothesis, Ferreira worked with Dr. Peter Byer and Michael Dorschner genetics experts in the University of Washington School of Medicine’s Department of Pathology, and with Dr. William Dobyns of the Department of Pediatrics, and other colleagues. They set about to compare the genes from cells in the vessel walls affected by the aneurysm and cells from the skin patches with those from tissues that were not affected. They found the genes were the same except for a change in one base pair in the DNA sequence of one gene.

That gene, Dorschner said, coded for a protein called platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta, or PDGFRB. The mutation caused the change of one amino acid in a crucial part of the protein.

“We know platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta is involved in vascular development, so it made sense that if a mutation occurred sometime during embryonic development it could lead to the formation of defective vessel walls,” Dorschner said.

Normally, PDGFRB acts as a kind of “on-off” switch that regulates key cellular activities. The change caused by the mutation, however, left PDGFRB stuck in the “on” position, thereby sabotaging the receptor’s regulating function. Such activating mutations are called “gain of function” mutations.

Gain in function mutations in PDFGRB also play a role in a number of cancers. These have been successfully treated with a PDGFRB inhibitor called sunitinib. To see whether this drug might be used to treat fusiform aneurysms, the researchers created cell lines in which they inserted the abnormal gene from the first patient case and genes from five other cases who also had mutations affecting the same region of the protein.

They found the drug did indeed turn off PDGFRB in four of five of the cases, suggesting the drug might be able to prevent aneurysms from forming and shrink or stabilize those that already existed. In the one case where it did not work, sunitinib was unable to bind to the mutated version PDGFRB and shut it down.

The findings suggest that mosaicism may be behind saccular aneurysms as well as other sporadic disorders whose causes are unknown, said Dorshner.

“Mosaicism may play a greater role in disease than we’ve thought,” he said.