By Teresa Wiltz, Stateline, Stateline

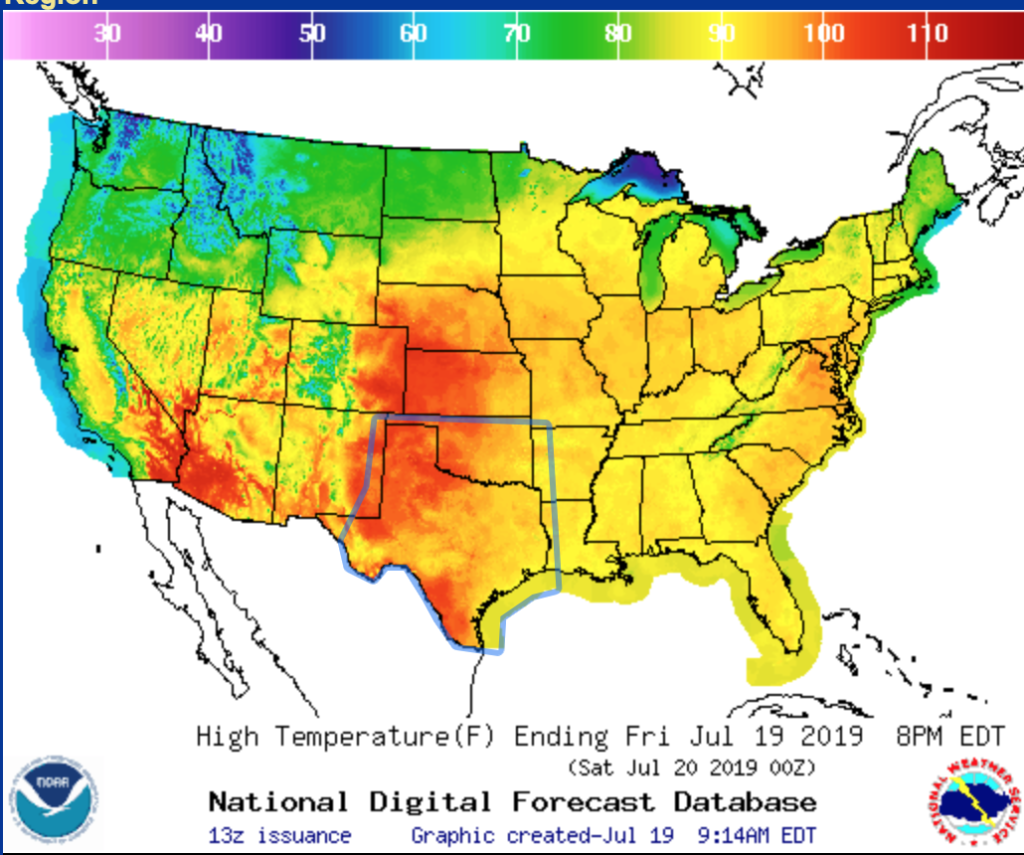

As a heat wave clamps down on much of the nation, cities are scurrying to provide shelter and assistance to the most vulnerable: the homeless and the elderly.

Temperatures are expected to rise to dangerous levels along the Eastern seaboard and in the Midwest, with heat indexes expected to top 100 degrees and nightly lows in some places failing to fall below 80.

Extreme heat can be deadly for anyone. But people living on the streets and seniors living on their own without air conditioning are particularly susceptible.

“The answer is pretty simple,” said Steve Berg, vice president of programs and policy for the National Alliance to End Homelessness, a research and advocacy group based out of Washington, D.C. “Have someplace with air conditioning that people can come to.”

Around the country, cities are mobilizing outreach teams, armed with copious amounts of water, to check on homeless people and provide transportation to get them to cooling centers. Some are even sending out text alerts to people experiencing homelessness to advise them of 24-7 cooling centers. Meanwhile, public housing agencies are regularly checking in on elderly and disabled residents.

“We are treating this as the emergency it is,” said Josh Kruger, communications director for the Philadelphia Office of Homeless Services.

In the nation’s capital, which is expected to have a heat index of 115 degrees over the weekend, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser, a Democrat, declared a state of emergency through the weekend. City officials are keeping “low-barrier” shelters open round the clock, so that people can get inside and cool off, said Carter Hewgley, senior adviser for the District of Columbia’s Department of Human Services.

To stay in a low-barrier shelter, people don’t have to undergo a criminal background check or a drug test. Under normal circumstances, those shelters open their doors at 5 p.m., and people must leave by 9 a.m. the next morning.

“You don’t want people dying from heat stroke because people didn’t want to come inside because they didn’t want to get drug tested,” Berg said.

Hewgley said the city also is sending out text blasts to homeless people to let them know where they can find refuge from the heat.

City officials are encouraging residents who see people in distress — those who are showing symptoms of heat stroke, or who are wandering the streets dressed inappropriately for the weather, for example — to call hotlines, so that a team can be dispatched to help them.

“Folks might not know that there are cooling centers available,” Hewgley said. “Or they might need water. Call and tell us.”

Chicago has extended the hours for cooling centers throughout the city, from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m., said Alisa Rodriguez, Chicago’s deputy commissioner of Homeless Services. Regional senior centers also have extended hours. And the city is working with homeless shelters to make sure that they keep their doors open 24-7 and keep their clients indoors as much as possible.

The city learned how to mobilize quickly thanks to a previous extreme weather event: January’s polar vortex, Rodriguez said.

During that event, the city was flooded with 311 calls from anxious friends and family members worried about the elderly, disabled and homeless, she said. The city coordinated with police and fire departments to conduct well-being checks.

The Chicago Public Housing Authority also is knocking on the doors of residents who are elderly or disabled three times a day to make sure that they are OK and that temperatures in their homes are at a safe level. Air conditioner units will be given out on an emergency basis, agency spokeswoman Molly Sullivan said.

New York City officials have declared a code red, which means they redouble their efforts to encourage the homeless to come indoors and increase the number of teams working round the clock who make regular, repeated contact with people on the streets.

“Homeless New Yorkers seeking shelter during extreme weather in New York City will not be turned away,” said Arianna Fishman, press secretary for the city’s Department of Homeless Services.

Meanwhile in Maryland, the Montgomery County Council is considering a measure that would require landlords to provide working air conditioning in all rental properties. It would be the first law of its kind in the region.

With climate change, cities will likely have to stay on alert and be ready to act, said Kruger of Philadelphia.

“Who knows how far off into the future we’re going to have to deal with this.”