Restricting SNAP benefits could hurt millions of Americans – and local communities

Cindy Leung, University of Michigan and Julia A. Wolfson, University of Michigan

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is trying to restrict access to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits.

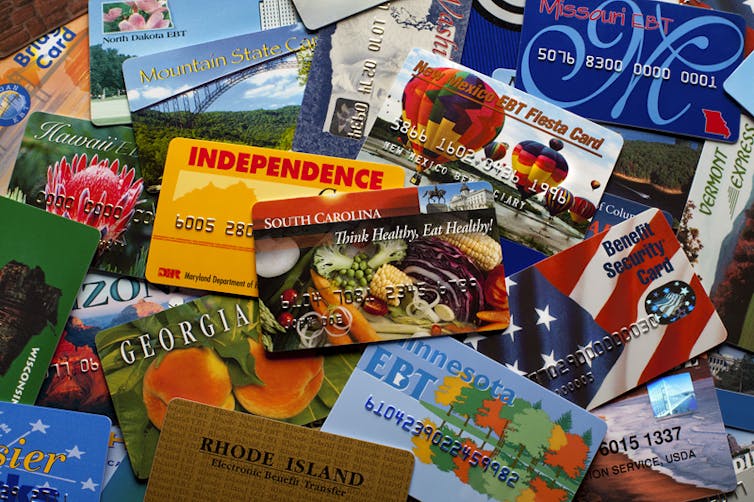

SNAP is the primary way the government helps low-income Americans put food on the table. According to the government’s own calculations, an estimated 3.1 million people could lose SNAP benefits, commonly referred to as food stamps, through a new proposal that would change some application procedures and eligibility requirements.

We are nutrition and food policy researchers who have studied the effects of SNAP on the health and well-being of low-income Americans. Should this change go into effect, we believe millions of Americans, especially children, and local communities would suffer.

Helping families and the economy

SNAP helped 39.7 million Americans buy food in 2018.

Federal research has found that the program reduces hunger, particularly in children – who make up 44% of its beneficiaries.

Hunger and poor nutrition harm children’s health and hinder their development. Kids who don’t get enough to eat have more trouble at school and are more likely to experience mental health problems. One research team found that people who had access to SNAP as children earned higher incomes and were less likely to develop chronic diseases like diabetes once they grew up.

“My eating habits have improved where I can eat more healthy than before,” a Massachusetts woman who had recently been approved for SNAP told us. “It is like night and day – the difference between surviving and not surviving.”

SNAP benefits also ripple through the economy. They lead to money being spent at local stores, freeing up cash to pay rent and other bills. Every US$1 invested in SNAP generates $1.79 in economic activity, according to the USDA.

Trying again and again

The Trump administration has repeatedly attempted to slash SNAP and make it harder for people who qualify for benefits to get them.

Its 2018, 2019 and 2020 budget proposals all called for cutting spending on food stamps by about 25%.

The Trump administration also worked with Republicans in Congress to try to tighten eligibility requirements. Had this policy been implemented, all beneficiaries between the ages of 18 and 59 deemed “able-bodied” would have had to prove they were working at least 20 hours per week or were enrolled in school. According to government projections, some 1.2 million Americans would have eventually lost their benefits as a result.

Congress, which would have needed to approve the change for it to take effect, rejected it in December 2018. The White House then sought to change work requirements through a new rule that has not yet taken effect.

In July 2019, the Trump administration again sought to restrict access to food stamps without any input from Congress, this time by going through Temporary Assistance for Needy Families – a program that gives low-income families with children cash to cover childcare and other expenses.

Currently, most states automatically enroll families in SNAP once they obtain TANF benefits. The new rule would prevent states from doing this. Even though 85% of TANF families also get SNAP benefits, the vast majority of them still live in poverty.

The government is seeking comments from the public about this proposed change through September 23, 2019.

Replacing food stamps with ‘harvest boxes’

Other changes to SNAP could also take a toll.

The Trump administration’s proposed budgets have also called for changing how the government helps low-income families get food they have trouble affording. Its 2019 budget proposal called for replacing half of SNAP benefits with what it called “harvest boxes” of nonperishable items like cereals, beans and canned goods.

According to research we conducted with low-income Americans, 79% of SNAP participants opposed this proposal, with one of the primary reasons being not being able to choose their own foods.

“People who are struggling are already demoralized,” a New Mexico woman who uses SNAP benefits told us. “Being able to make our own food decisions is something that keeps us feeling like human beings.”

Congress rejected the concept but the White House included it again in its 2020 budget draft.

Advocates for food aid fear that recent proposals to change how SNAP works would reduce the share of Americans who get these benefits by making it harder to qualify and enroll in the program. Should this major transformation ever occur, children and families won’t have access to critical benefits that help them avoid going hungry.

Tracking the demand for food stamps

Although the Trump administration has until now largely failed in its effort to cut SNAP spending, the number of people getting food stamps is already declining. This trend began during the Obama administration, in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

Since the economy is doing well overall, the number of people on food assistance programs has fallen. The reason for the decline is that the number of people who are eligible for these benefits rises when the economy falters and falls when conditions improve. As a result, the government is spending less on food stamps without cutting the SNAP budget.

Case in point, 7 million people have already left SNAP due to better economic stability. In parallel, federal spending on SNAP budget has dropped from $78 billion in 2013 to $64 billion in 2019.

If the Trump administration wants to shrink SNAP, reduce costs and have fewer low-income Americans receive benefits, we believe that the best thing it can do is to keep working to improve the economy – particularly for low-income Americans, who have been reaping fewer benefits from the improving economy than others in recent years.

Cindy Leung, Assistant Professor of Nutritional Sciences, University of Michigan and Julia A. Wolfson, Assistant Professor of Health Management and Policy, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.