Hiba Jebeile, University of Sydney and Tracy Burrows, University of Newcastle

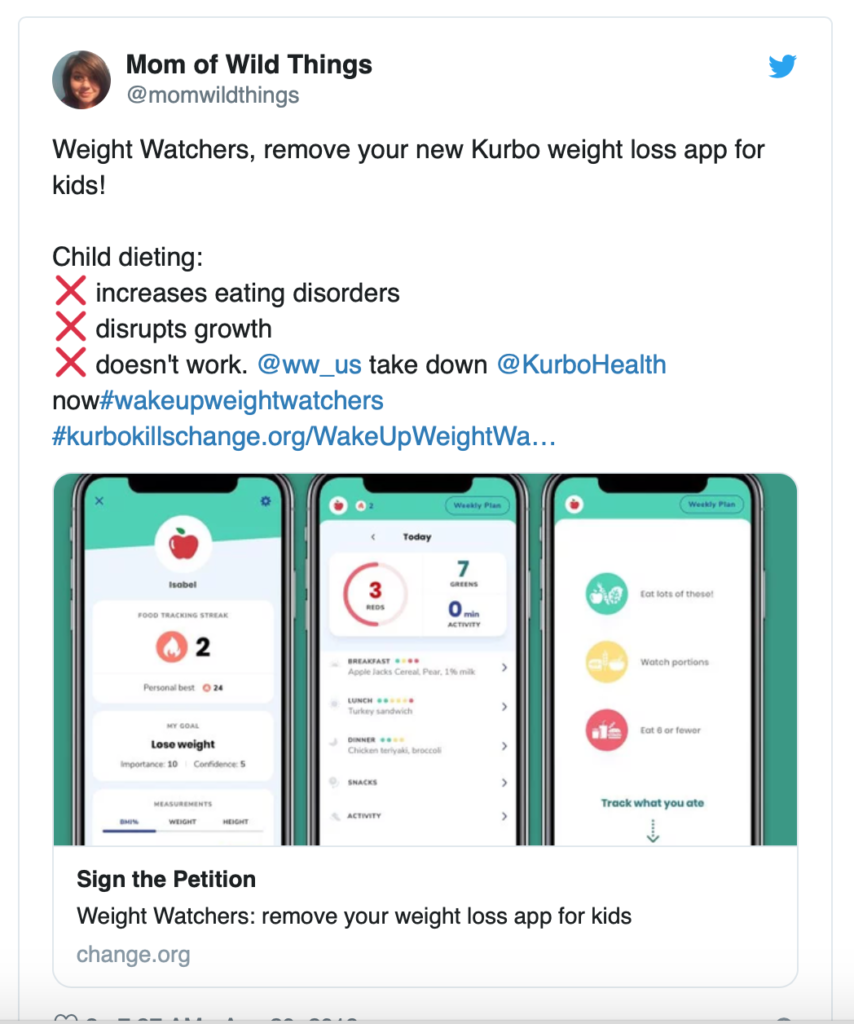

Over the last week, a weight loss app targeted at children and teenagers aged 8-17 has sparked concern among health professionals and parents around the world.

More than 90,000 people have signed an online petition calling for withdrawal of an app called Kurbo.

Kurbo was launched in 2014. WW (formerly Weight Watchers) bought it last year and have recently relaunched it.

It’s currently only available in the United States, but we could see it launched in Australia.

Read more: More than one in four Aussie kids are overweight or obese: we’re failing them, and we need a plan

Overweight and obesity affect one in four Australian children and adolescents. Excess weight is likely to persist into adulthood and is associated with the development of chronic disease.

While there are calls for better treatment options, the way treatments for obesity are delivered is important.

Unsupervised use of an app that encourages children to track their weight carries the danger of perpetuating body image issues and leading to disordered eating.

The traffic light system

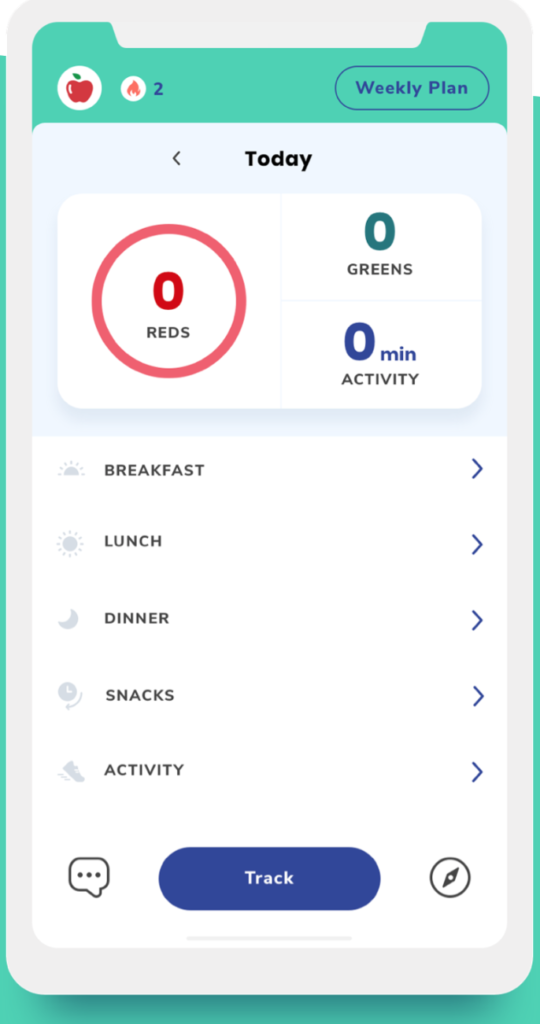

Kurbo is based on the traffic light system, a family-based lifestyle intervention developed by Stanford University.

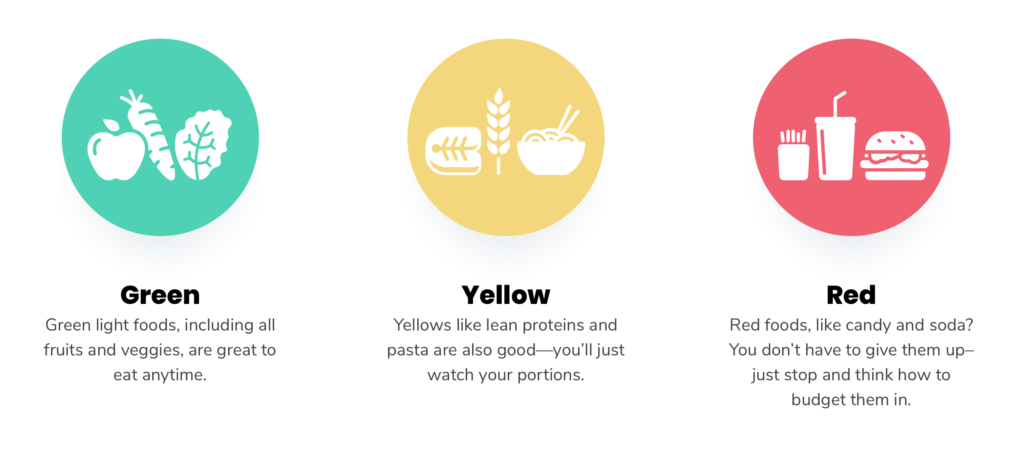

This system groups foods into three categories:

- “red” (limit or budget them into your plan, for example lollies and soft drinks)

- “amber” (watch your portion, for example lean meat and pasta)

- “green” (eat any time, for example fruit and vegetables)

The aim of this system is to encourage families to eat more “green” foods and less “red” foods. The traffic light system has been shown to be effective in improving weight-related outcomes in children treated for overweight or obesity without a negative effect on eating behaviours, when used by the whole family through a supported program.

But Kurbo uses the traffic light system as an online app targeted to children directly, rather than to parents or families. Children aged under 13 need a parent’s permission to download the app, but those over 13 don’t.

Alongside other features, the paid version of the app provides children with a weekly video-chat check-in with a health coach. The training health coaches have had in child obesity, mental health and body image is unclear.

Read more: Kids’ diets and screen time: to set up good habits, make healthy choices the default at home

Possible pros

Technology and apps providing health services are growing in number, and can be convenient and cost effective.

Importantly, families actually want to use technology for more flexibility in the way they receive nutritional support.

In one study of a telehealth nutrition intervention with a website, Facebook group and text messages, benefits included ease of self-monitoring and increased access to services for families living in regional or remote areas. This intervention resulted in improved eating habits in children.

Apps in particular are a promising option because they’re portable and can connect with other technologies.

Read more: Let’s untangle the murky politics around kids and food (and ditch the guilt)

Kurbo was one of three apps targeted to children identified in a 2016 review of mobile apps for weight management. The version of the app evaluated at the time of the review was found to meet eight evidence-based strategies for weight management: self-monitoring, goal-setting, physical activity support, healthy eating support, social support, gamification, and personalised feedback delivered via a health coach.

Technology evolves rapidly, so it’s unclear if these features all remain in the current version. As we’re based in Australia, and the app is only available in the US, we can’t access the app directly to verify this.

Kurbo reports 90% of pilot study participants maintained or reduced their weight, and experienced “higher levels of happiness, self-confidence and self-esteem”.

But importantly, the app hasn’t been researched scientifically and independently.

Possible cons

Targeting children with a weight-focused app brings up concerns about the potential risk of developing disordered eating or eating disorders.

Research has shown an association between self-reported dieting during adolescence and an increased risk of binge eating and eating disorders. These data highlight the risk of unsupervised dietary change.

Targeting children, rather than parents, shifts the responsibility to the child. With the foods available to them largely out of their control, this could lead to internalised feelings of failure if they cannot comply with the program.

While Kurbo is designed to develop healthy eating behaviours, the marketing materials send different messages. This includes the use of before and after pictures in children as young as eight years old to promote success stories.

We don’t know how these will impact children, both in the short and long term. Children are at an age where body image is fragile due to changes occurring in preparation for, or during, puberty.

The importance of supervision

A recently published review of 30 studies found professionally run obesity treatment programs, conducted in children and adolescents, were associated with reduced eating disorder risk.

Treatment programs included in the review involved regular face-to-face contact with a trained professional; usually a dietitian, nutritionist or psychologist.

This review highlights that mode of delivery and length of contact are important aspects of weight management.

Read more: How many people have eating disorders? We don’t really know, and that’s a worry

There have been limited studies assessing children’s risk of developing eating disorders following online interventions, so the impact of Kurbo on this remains unknown.

Kurbo states it will monitor participants for safety concerns including rapid weight loss and mental health issues, notifying parents if these occur.

As a commercially available program, it is unclear how and if such safety measures will be acted upon. This compares to a program delivered in a health setting or as a clinical trial, which would have strategies in place, approved by an ethics committee, to identify unexpected adverse events.

Weight loss isn’t always the right goal

Australian guidelines recommend weight maintenance rather than weight loss for most children before puberty, because it’s expected their weight and height will increase as they grow.

Weight loss is recommended, with the support of a health professional, for adolescents with moderate to severe obesity and/or those who have started to develop complications such as pre-diabetes. Treatment should be targeted to the individual lifestyle, and involve regular contact.

Read more: Five things parents can do to improve their children’s eating patterns

If parents are concerned about their child’s weight, they should consult their GP or an Accredited Practising Dietitian, to assess if intervention is required, and suitable options.

Hiba Jebeile, PhD candidate/Research Dietitian, University of Sydney and Tracy Burrows, Associate Professor Nutrition and Dietetics, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.