By Michael Ollove, Stateline

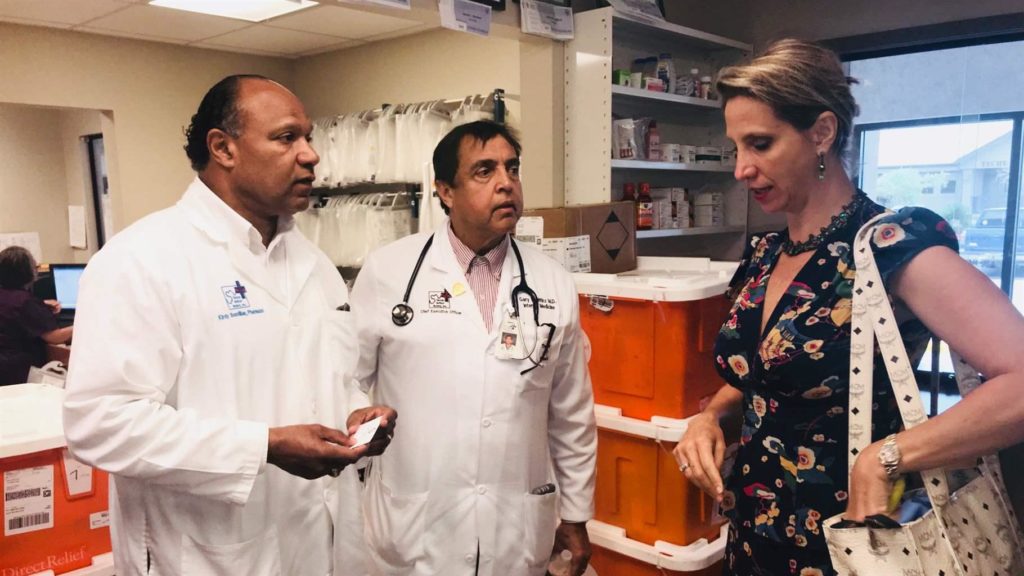

Down in the Louisiana bayou, Dr. Gary Wiltz is wondering how he’s supposed to run 14 community health centers and treat 30,000 patients without a large chunk of federal money. Again.

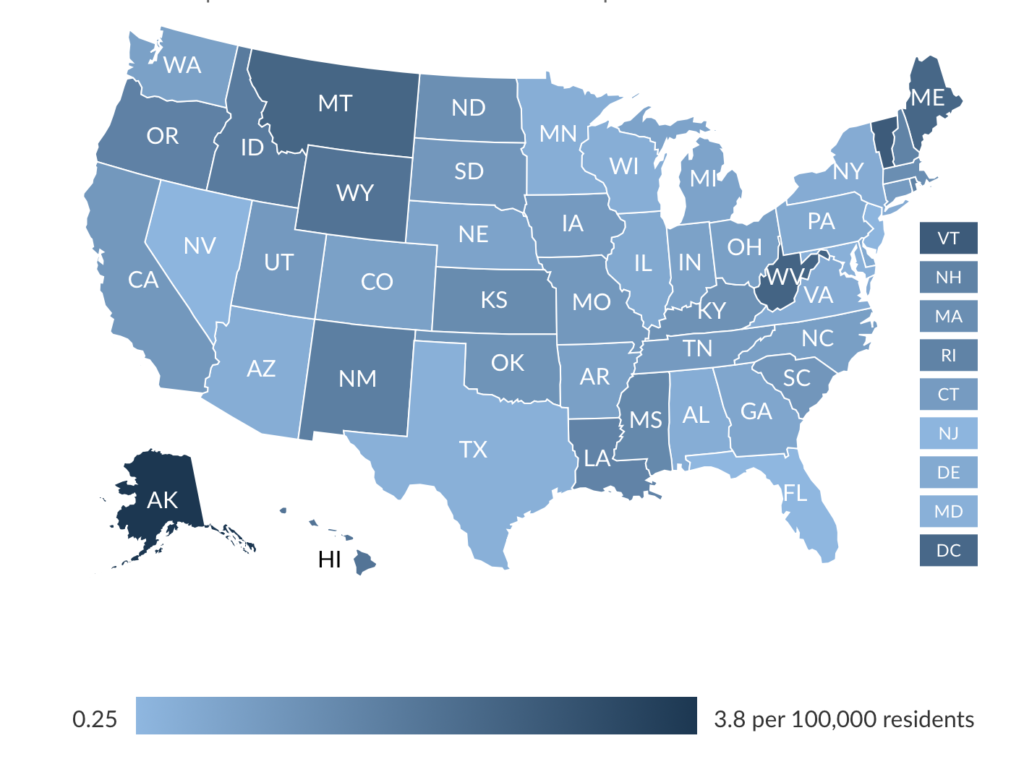

As happened in 2017, Congress is on the precipice of failing to meet the Sept. 30 deadline for reauthorizing the Community Health Center Fund that supports nearly 1,400 community health centers, which treat more than 27 million predominately poor patients.

As a result — according to a recent survey of community health centers conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation — nearly 60% of centers have frozen hiring or are considering doing so; 42% already have or might reduce staff hours; and 42% have laid off staff or are contemplating it. Many may delay planned renovations or expansions, reduce operating hours or shutter locations.

Two years ago, the money didn’t come through until five months after the deadline, causing some health centers to lay off staff, curtail operating hours and suspend planned building projects and new programs.

Wiltz, CEO of the Teche Action Clinic in sugar cane-rich western Louisiana, said they’re in the same situation now.

“It’s very frustrating and unsettling as an administrator that we have to keep going through this every two years.”

Congressional Democrats and Republicans say they want to provide money for the program, but bills to do so are stalled.

“We saw just how painful it was for communities across the country last time,” U.S. Sen. Patty Murray of Washington, the ranking Democrat on the Senate health committee, said in an email. “I think no one wants to see that happen again.”

The Republican chairman of the health committee, Tennessee’s Lamar Alexander, in an email cited his support for longer funding cycles for community health centers.

Committees in both the Senate and House have passed bills that have not been taken up by their full chambers.

The holdup comes in part because controversial provisions have been added to the bills, most notably one that would stop surprise medical billing. The House and Senate bills also differ on the amount, source and length of funding (the Senate bill would provide money for five years; the House for four).

What’s at Stake

The Community Health Center Fund was created in 2010 under the Affordable Care Act, which provided money for five years. Congress extended federal dollars twice more, but only for two years each, in 2015 and 2018 (retroactive to the previous September after missing its deadline). The second two-year extension is set to expire next week.

Two other programs that help medically underserved populations are in a similar predicament. Congress has failed to renew funding for the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education Program — which provides grants to health centers in underserved areas for the training of medical and dental residents — and the National Health Service Corps, which provides scholarships to and repays the loans of health care providers who agree to work in economically distressed areas with a shortage of medical professionals.

The programs are intertwined: A majority of the 57 teaching health centers also are community health centers, and most of the more than 10,000 health service corps members work out of community health centers.

The amount of money that goes to the community health centers, however, dwarfs that of the other programs. When Congress finally reauthorized the Community Health Center Fund in February 2018, it provided $4 billion for fiscal 2018 and another $4 billion in 2019.

The annual appropriation bills Congress adopted sent the centers an additional $1.6 billion each of those years.

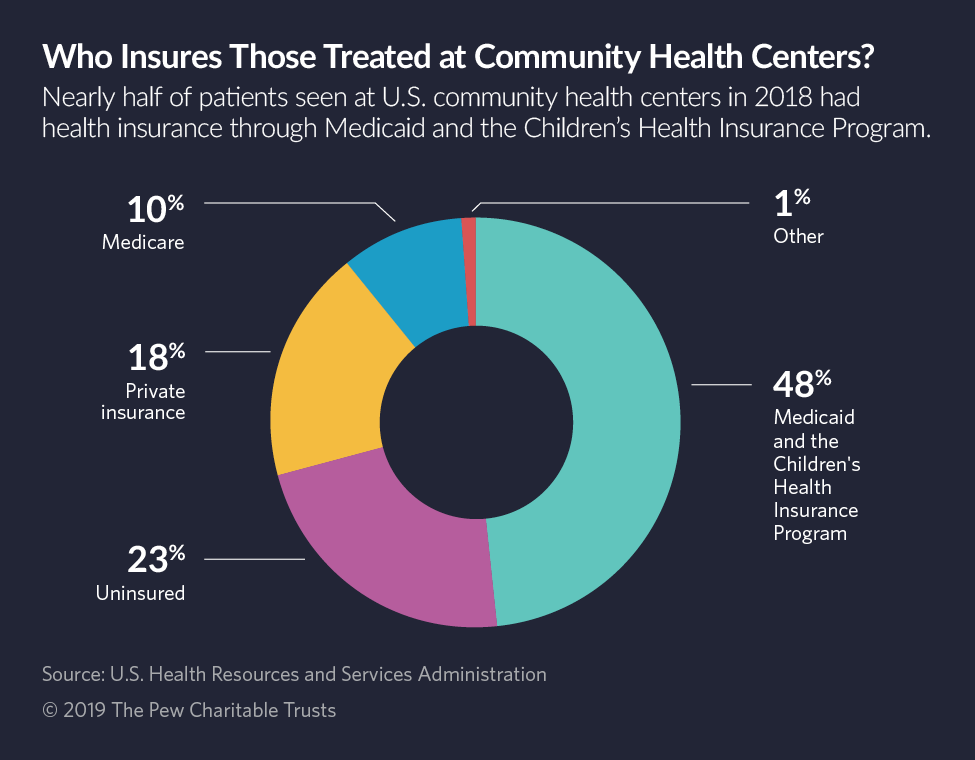

Those two streams of federal money represent as much as 30% of the revenue for some community health centers, according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation. The rest mainly comes from insurance, both private and public, including Medicaid and Medicare.

This year, the teaching health centers received $126.5 million in federal money, and the health service corps got $310 million.

It appears that Congress will fail to reauthorize the Community Health Center Fund or pass 2020 appropriations bills by the Oct. 1 start of the new fiscal year. Instead it is working on a continuing resolution to keep the government open through Nov. 21. That still leaves community health centers facing an uncertain future.

“Picture that you’re running a health center and have to figure out how you’re going to do it when the money isn’t coming in,” said Steve Carey, chief strategy officer for the National Association of Community Health Centers. “Who are you not going to treat? Which doctor are you going to let go? What technology are you going to do without? These are the places that are providing local care for veterans, that are at the front lines in the opioid addiction issues, that are involved in maternal mortality.”

Termites and a Leaky Roof

Wiltz, working for the health service corps, was assigned to the Teche Action Clinic as medical director and its only physician in 1982. Back then, the clinic operated out of a termite-infested house with a leaky roof. There was a $100,000 budget, seven employees and a good chance of going under.

After his obligation ended, he did what the corps hopes its members will do: He stayed to practice there.

Now Teche has 220 employees, operates in six Louisiana parishes and has a budget of about $24 million for its current fiscal year, its chief financial officer, William Brent, said.

About $5.4 million comes from federal grants for community health centers, Brent said, and about $8.8 million from Medicaid, the health plan for the poor jointly financed by states and the federal government. The rest is from Medicare, private insurance, other federal, state and local programs, and other sources.

Louisiana expanded Medicaid in 2016, which, Wiltz said, reduced the uninsured rate among his clinic’s patients from as high as 65% to no more than 10%.

The change, he said, led to many patients gaining treatment for previously undiagnosed cases of diabetes and colon and breast cancer. Teche provides not just primary care but also mental health, dental and pharmacy services. It also runs four school-based health clinics.

Because the federal money is so uncertain, Wiltz said, he has delayed hiring a new OB-GYN to replace a retiring doctor. He may cut back the extended hours at some clinics and put off opening another one.

“No entity in the world can make any long-term, concrete, sustainable plans without stable funding,” he said. “You couldn’t get a mortgage if you didn’t have a stable set of resources, and you can’t run a health clinic that way either.”

In Washington state, HealthPoint — with 17 clinics in the Seattle area serving mostly low-income patients — faces similar difficulties, said its CEO, Tom Trompeter.

He said 15% to 20% of his medical staff are in the health service corps. “Being able to rely on that funding is incredibly helpful in recruiting,” Trompeter said. “If we can’t be confident in saying to recruits, ‘We’ll help you pay off your school debts,’ we’re going to lose them to others.”

Teaching health centers face similar concerns. In Tennessee, the delay of federal money in 2017 forced the Resurrection Health Family Medicine Residency Program in Memphis to close for good — according to Cristine Serrano, executive director of the American Association of Teaching Health Centers — and sent 26 medical residents scrambling to find programs that would take them on.

“Imagine being within 6 months of graduating,” she said in an email, “and then they have to start over at a new program.”

Stateline is an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy. Since its founding in 1998, Stateline has maintained a commitment to the highest standards of non-partisanship, objectivity, and integrity. Its team of veteran journalists combines original reporting with a roundup of the latest news from sources around the country. Stateline focuses on four topics that are key to state policy: fiscal and economic issues, health care, demographics, and the business of government.