NIH launches first U.S. clinical trial of patient-derived stem cell therapy to replace dying cells in retina

From the National Institutes of Health

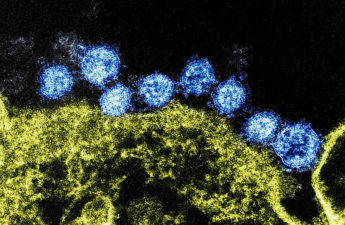

The researchers will take a patient’s own blood cells, and in a lab, convert them into iPS cells capable of becoming any type of cell in the body. The iPS cells are then programmed to become retinal pigment epithelial cells, the type of cell that dies early in the geographic atrophy form of AMD. NEI

Researchers at the National Eye Institute (NEI) are launching a clinical trial to test the safety of a novel patient-specific stem cell-based therapy to treat geographic atrophy, the advanced “dry” form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of vision loss among people age 65 and older. The geographic atrophy form of AMD currently has no treatment.

“The protocol, which prevented blindness in animal models, is the first clinical trial in the U.S. to use replacement tissues from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC),” said Kapil Bharti, Ph.D., a senior investigator and head of the NEI Ocular and Stem Cell Translational Research Section. The NEI is part of the National Institutes of Health.

The therapy involves taking a patient’s blood cells and, in a lab, converting them into iPS cells, which have the potential to form any type of cell in the body. The iPS cells are programmed to become retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, the type of cell that dies early in the geographic atrophy stage of macular degeneration.

RPE cells nurture photoreceptors, the light-sensing cells in the retina. In geographic atrophy, once RPE cells die, photoreceptors eventually also die, resulting in blindness. The therapy is an attempt to shore up the health of remaining photoreceptors by replacing dying RPE with iPSC-derived RPE.

Before they are transplanted, the iPSC-derived RPE are grown in sheets one cell thick, replicating their natural structure within the eye. This monolayer of iPSC-derived RPE is grown on a biodegradable scaffold designed to promote the integration of the cells within the retina. Surgeons position the patch between the RPE and the photoreceptors using a surgical tool designed specifically for that purpose.

Under the phase I/IIa clinical trial protocol 12 patients with advanced-stage geographic atrophy will receive the iPSC-derived RPE implant in one of their eyes and be closely monitored for a period of at least one year to confirm safety.

A concern with any stem cell-based therapy is its oncogenic potential: the ability for cells to multiply uncontrollably and form tumors. In animal models, the researchers genetically analyzed the iPSC-derived RPE cells and found no mutations linked to potential tumor growth.

Furthermore, the use of an individual’s autologous (own) blood cells is expected to minimize the risk of the body rejecting the implant.

Should early safety be confirmed, later study phases will include more patients to assess the efficacy of the implant to prevent blindness and restore vision in patients with geographic atrophy.

A Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirement for moving forward with the clinical trial was the establishment of good manufacturing practice (GMP) protocols to ensure that the iPSC-derived RPE are a clinical-grade product. GMP protocols are key for making the therapy reproducible and for scaling up production should the therapy receive FDA approval.

The preclinical research for the trial was supported by the NEI Intramural Research Program and by an NIH Common Fund Therapeutic Challenge Award. The trial is being conducted at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD.