Editor’s note: If you or someone you know needs help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-8255.

By Christine Vestal, Stateline

ATLANTA — Brian Anderson, an imposing man with a rich baritone voice, dwarfs his office chair at the Georgia Crisis and Access Line. He talks softly about the first time he tried to end his life.

It was a collect call to his father from a pay phone in Hoboken, New Jersey, that saved him, he said. “I’d made up my mind that my life was over, and I wanted my father to pray for my soul. I told him, ‘Don’t pray for me, that person is finished – pray for my soul.’ I’d already suffered enough in this life, I didn’t want to suffer more in the afterlife.”

Anderson made the call in 1984, when he was 19, after he’d taken fistfuls of drugs to end his pain, he said. He made another attempt to end his life seven years later, before mental health treatment helped him recover.

Now, he talks to people who may be having some of the same thoughts and feelings he had back then. He said he assures them that there are ways to turn their lives around. He’s done it. “I give them hope,” Anderson said.

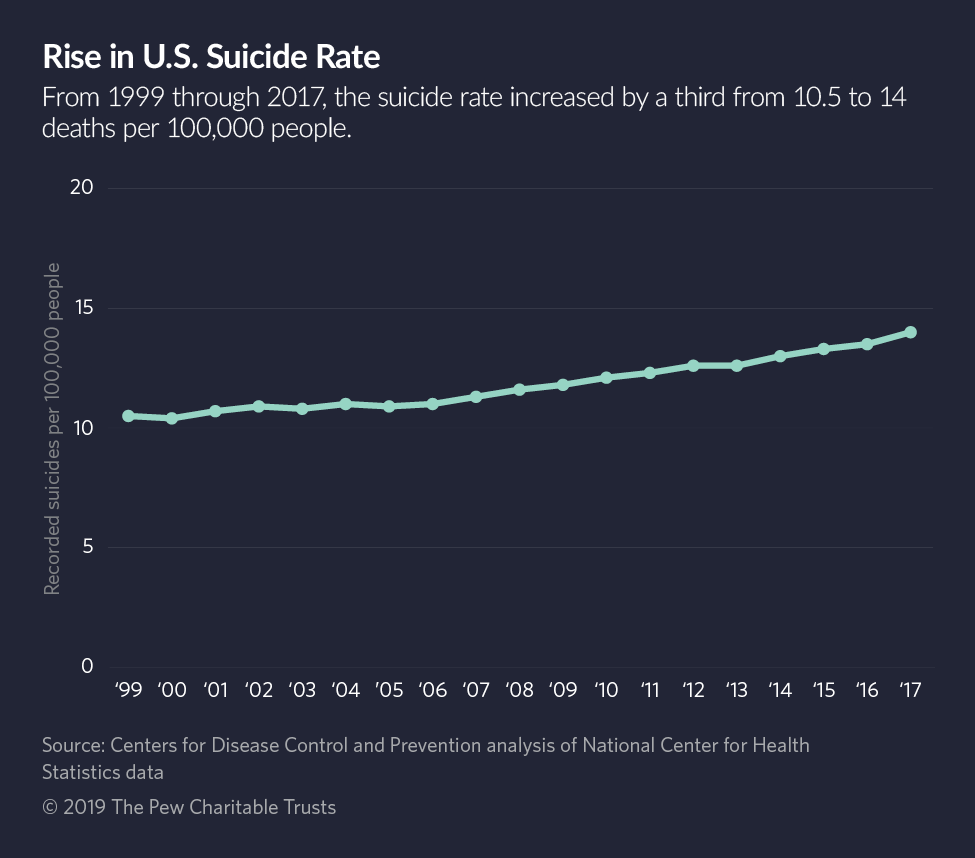

Suicide rates in the United States have climbed steadily over the past two decades, contributing, along with drug overdoses, to a decline in the average U.S. life expectancy for the third year in a row. The demographers who first identified this trend have called it “deaths of despair.”

In response, Congress enacted the National Suicide Hotline Improvement Act of 2018, to encourage more people to seek help. It directed the Federal Communications Commission to study the feasibility of creating a three-digit suicide hotline number, like 9-1-1, that more people could remember.

Last week, the FCC unanimously approved a proposal to set aside 9-8-8 as the replacement for the existing national suicide hotline number: 800-273-8255. The new number isn’t expected to go live for a year or more.

“The problem we’ve always had is getting more people to find us,” said FCC Chairman Ajit Pai. The shorter and simpler number could increase access to suicide services, reduce stigma and ultimately save lives, he said.

Call Surges

The easy-to-remember number is projected to generate a substantial increase in the number of callers, which suicide prevention experts roundly support.

But the network of local call centers that respond to distraught and suicidal callers is woefully underfunded, said John Draper, director of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, which provides infrastructure and support for the nation’s more than 170 local suicide hotlines.

When you call the National Lifeline, 1-800-273-8255, your call is routed to a local call center closest to the area code you call from. If your community doesn’t have a call center or they don’t answer quickly enough, your call rolls over to one of six national call centers that act as a backup.

Last year, 2.2 million people called the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number, up from 46,000 in 2005. Another roughly 14 million calls come through local crisis lines like Georgia’s — 800-715-4225.

With few exceptions, local call centers are funded by a patchwork of inconsistent state, local and private funding that has failed to increase to meet rising demand, Draper said.

Georgia is one of the exceptions.

Since 2006, the state has set the standard for comprehensive suicide prevention care — from its centralized statewide 24/7 crisis line with a $10 million annual budget and 400 plus full-time employees in downtown Atlanta to dozens of crisis stabilization centers, community mental health facilities and mobile crisis units serving all 159 counties.

Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, New York City and Utah also have made substantial investments in suicide prevention. Even so, Draper said, roughly 60% of the nation’s suicide prevention call centers still receive no funding to answer calls forwarded from the national lifeline number.

As a result, the volume of calls that rolls over to national centers is rising. That’s less than ideal, since call centers are far more effective when the professionals who answer the calls are familiar with local mental health resources, which enables them to set up appointments, locate available psychiatric beds and, when needed, send a mobile crisis unit directly to the caller.

When calls come through Georgia’s statewide suicide prevention number, the licensed mental health professionals who answer the lines use a software system called “care-traffic control” to identify nearby mental health services with available appointments and beds, if needed.

The system also allows crisis line operators to access the callers’ medical records, so they can suggest clinicians, doctors and medical facilities they may have been to before.

Hotline History

The first local suicide prevention call line was established in 1958 in Los Angeles.

After that, local hotlines began to proliferate around the country. In Georgia, 27 regional hotlines were created over a 15-year period, until the state decided to close them in 2006 and create a statewide center in Atlanta.

<div class='tableauPlaceholder' id='viz1576860234258' style='position: relative'><noscript><a href='https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2019/12/20/new-suicide-prevention-number-could-lead-to-surge-in-calls'><img alt=' ' src='https://public.tableau.com/static/images/54/54JGM84YP/1_rss.png' style='border: none' /></a></noscript><object class='tableauViz' style='display:none;'><param name='host_url' value='https%3A%2F%2Fpublic.tableau.com%2F' /> <param name='embed_code_version' value='3' /> <param name='path' value='shared/54JGM84YP' /> <param name='toolbar' value='yes' /><param name='static_image' value='https://public.tableau.com/static/images/54/54JGM84YP/1.png' /> <param name='animate_transition' value='yes' /><param name='display_static_image' value='yes' /><param name='display_spinner' value='yes' /><param name='display_overlay' value='yes' /><param name='display_count' value='yes' /><param name='tabs' value='no' /><param name='filter' value='publish=yes' /></object></div> <script type='text/javascript'> var divElement = document.getElementById('viz1576860234258'); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName('object')[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.width='100%';vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+'px';} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.width='100%';vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+'px';} else { vizElement.style.width='100%';vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*1.77)+'px';} var scriptElement = document.createElement('script'); scriptElement.src = 'https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js'; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement); </script>Hurricane Katrina was the impetus, said Melissa Sperbeck, who directs the statewide crisis line at the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities. With thousands of traumatized people from the Gulf area seeking refuge in Georgia, it became clear that mental health services had to become more efficient, she said.

Then in 2010, Georgia settled a disabilities case with the U.S. Justice Department, in which the state was required to invest in enough community mental health services to allow people with disabilities to live independently, outside of state mental hospitals.

Funding for Georgia’s crisis line and related community services was a part of that agreement.

But while Georgia was consistently funding its suicide prevention efforts, many states were cutting their mental health budgets during the recession that began in 2008, said Dr. Brian Hepburn, director of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors.

Now some states are starting to reinvest in hotlines and other community services, because of the rise in suicide rates, he said.

In 2017, more than 47,000 people in the United States took their lives, making suicide the 10th-leading cause of death, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The same year, 1.4 million adults attempted suicide, an increase of 33% since 1999, and 10.6 million adults reported seriously considering suicide, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. STATELINE STORY October 12, 2017’Katrina Brain’: The Invisible Long-Term Toll of Megastorms

“When you have something like 9-8-8, it can be a game changer in erasing or at least reducing the stigma against mental illness in this country,” Draper said. “Right now, a mental health emergency is responded to with police and ambulances. The moment people start to understand that for most people, that is not the right response, will be the moment that proper suicide prevention care will be validated.”

In October, the nonprofit that runs the lifeline awarded grants to 12 states — Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Nevada, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont and Virginia — to help them answer more calls from in-state residents who dial the national lifeline number.

Saving Lives

At Georgia’s Crisis Line call center last Monday, Keith Lisenbee was managing the 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. shift. It’s the busiest shift of the day, and Monday is always the busiest day of the week, said Lisenbee, who is the contact center supervisor. On average, the crisis line here receives roughly 700 calls a day.

Contrary to popular belief, call volume drops during the holidays, he said, because more people are connected to their friends and family and churches. It’s in January, after the holidays are over and some people experience an emotional letdown, when calls start to surge. STATELINE STORY June 11, 2019Coaxing Veterans Into Treatment to Prevent Suicides

But calls during the holiday season do tend to be more urgent, he said.

Lisenbee described a call on Sunday from a man who said he was alone and struggling with suicidal thoughts. The clinician on the phone with him decided the situation was serious enough to dispatch a mobile mental health team. The caller gave her his location and she asked him to stay there until the team arrived.

He called back 15 minutes later, and the same clinician got back on the phone, Lisenbee said. The first thing the caller said was, “I don’t think I’m going to make it.” He told her he was on a bridge over the metro tracks and planned to jump. But this time, he wouldn’t give her his location.

She heard a bystander talking to him in the background and asked the caller to hand the phone to him. He did, and the bystander gave her the location. She called 9-1-1 and the police rescued him.

“That was a win,” Lisenbee said.

But most calls don’t involve a mobile dispatch or the police. For most callers, a phone conversation with a trained suicide prevention professional rapidly de-escalates their emotional crisis.

Madelyn Gould, a professor at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, found through a series of interviews with callers to suicide hotlines that they were “significantly more likely to feel less depressed, less suicidal, less overwhelmed, and more hopeful by the end of calls.”

The professionals who answer calls at the Georgia crisis line have master’s degrees and are licensed mental health workers. They also receive three months of intensive on-the-job training, and their work is supported by cutting edge software and evidence-based counseling techniques.

Looking back on the call to his father in South Carolina from that Hoboken pay phone, Anderson said he realizes now that it was a near miracle that his father was able to quickly summon local family members to scoop him up and take him to the nearest hospital.

“He asked me where I was, and I looked up at the street sign next to me and told him.” Then, Anderson said, his father kept him on the line, praying for him, until two of his stepsisters showed up.

Stateline will not publish Dec. 23-27. Our next story will publish Monday, Dec. 30.

Stateline is an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy. Since its founding in 1998, Stateline has maintained a commitment to the highest standards of non-partisanship, objectivity, and integrity. Its team of veteran journalists combines original reporting with a roundup of the latest news from sources around the country. Stateline focuses on four topics that are key to state policy: fiscal and economic issues, health care, demographics, and the business of government.