By Christine Vestal, Stateline

WASHINGTON — Geoffrey Gibson, owner of Capital Vape Supply, watched his thriving, 7-year-old business wither last summer when vaping-related deaths started making headlines.

It picked up again after the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced in December that the lung illness that has killed at least 60 people and injured more than 2,600 was primarily caused by cartridges containing THC (the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana), not nicotine.

Now, Gibson and dozens of other vape shop owners in Washington, D.C., face another potential setback — a proposed city council bill that would outlaw all flavored vaping liquids. Similar efforts are sprouting up around the country as local and state officials try to curtail rampant teen vaping.

The number of adolescents who vape has more than doubled since 2017. An estimated 28% of high-schoolers and 11% of middle-schoolers are current vape users, according to a recent national survey by the CDC and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

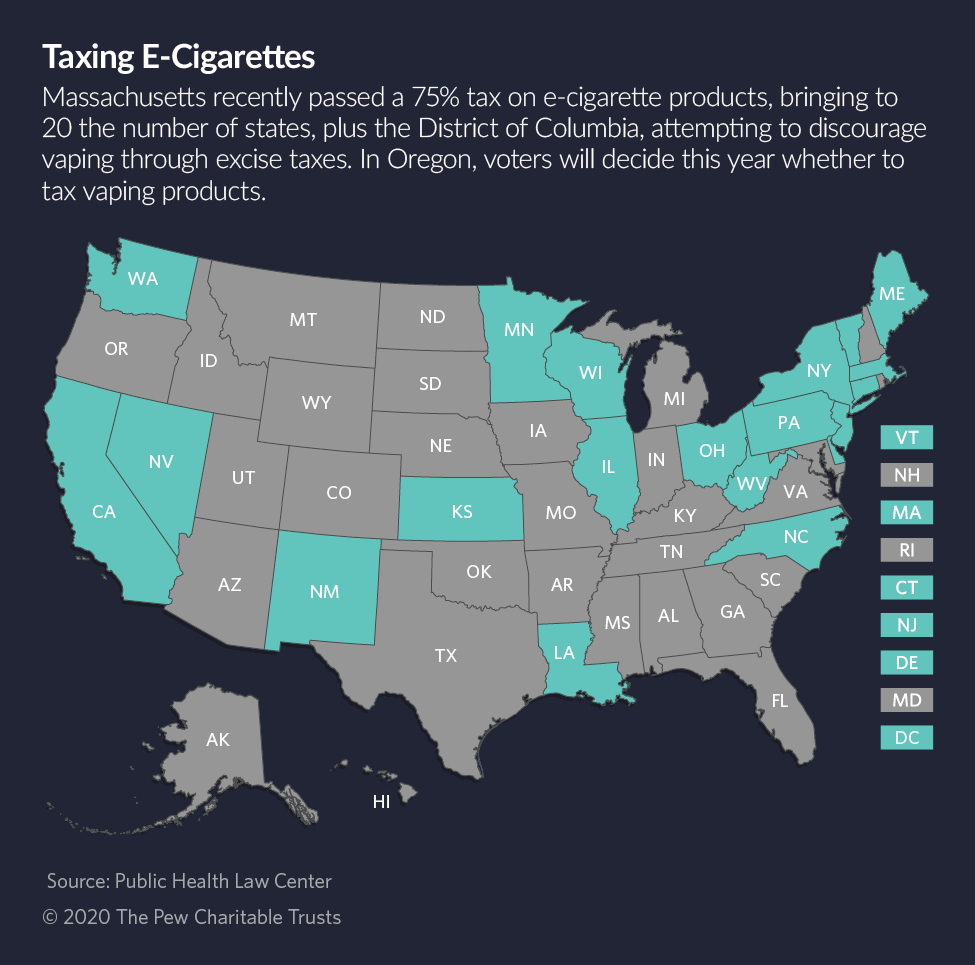

Other state tactics include levying hefty taxes on vaping products, restricting vape store zoning, requiring warning labels and otherwise limiting the sale and marketing of nicotine vaping liquids.

Nineteen states and the District of Columbia had raised the smoking age to 21 for both cigarettes and vaping when in late December the Trump administration raised the national smoking age to 21, effective immediately.

Major medical groups, the U.S. Surgeon General and anti-tobacco lobbyists are calling for an expansion of state and local flavor bans and other restrictions aimed at keeping the devices out of kids’ hands.

“This is an industry that spends $9 billion a year in marketing, and a lot of that is designed to get kids addicted,” said John Schachter, state policy director for the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. “Kids aren’t making a choice. They’re being targeted by a nefarious industry.”

But advocates for vapers, the vaping industry and some public health researchers say the emerging regulations could destroy a nascent industry that is proving to be the greatest boon to smoking cessation in decades.

They argue that over-regulating vaping products could force the more than 3 million adults who use them as a smoking alternative to seek dangerous, unregulated products on the black market or go back to smoking cigarettes, which kill more than 480,000 Americans every year. They also warn the same thing could happen to the kids they are trying to protect.

Because adolescent tobacco use declined more rapidly in the past five years than in the previous three decades, some researchers speculate that youth nicotine vaping, which started gaining momentum about five years ago, may have supplanted what would have been more harmful adolescent smoking.

Earlier this month, the CDC removed a website warning it had posted last year as the lung illness was sweeping the nation.

Now, instead of urging everyone to stop all types of vaping immediately, the agency is taking a more measured approach. The CDC’s website currently recommends that vaping products should not be used by youths, young adults, women who are pregnant or adults who do not currently use tobacco products. And it cautions adults using nicotine vaping products as an alternative to cigarettes not to go back to smoking.

Bans Expand

In November, Massachusetts became the first state to enact a permanent flavor ban on all tobacco products, including menthol cigarettes. New Jersey’s legislature passed a similar ban this month but did not include cigarettes.

Lawmakers in sixteen states — Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia and West Virginia — and Washington, D.C., are considering flavored vaping legislation.

In addition, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Los Angeles County and more than 250 other local governments banned the sale of flavored vaping products last year.

At the federal level, the Trump administration announced this month that the FDA would ban all flavors except tobacco and menthol in so-called closed system or cartridge-based products such as those made by Juul and NJOY, starting in February. Those are the easy-to-conceal, high-tech products that are preferred by teens, according to national surveys, and are sold online and in most gas stations and convenience stores.

Cartridge-based products in general contain a much higher percentage of nicotine than open-system or refillable tank vapes sold in stores like Capital Vape Supply.

The refillable tanks are the clunkier, low-tech devices that create a huge cloud of vapor and are primarily used by budget-conscious adults who either consider vaping a safer alternative to smoking or want to vape nicotine liquids in places where they can’t smoke cigarettes.

The administration said it was striking a balance between preserving flavored e-cigarettes for adults seeking to quit smoking while targeting the products most widely used by teens.

Still, small vape shops and the customers who use them to stay away from cigarettes aren’t out of the woods yet, said Gregory Conley, president of the Stamford, Connecticut-based American Vaping Association, which represents vapers.

A federal court ordered — in a lawsuit filed against the FDA by the American Academy of Pediatrics — vaping device-makers to file applications with the FDAshowing the liquids and their products are safe and help people stop smoking.

Juul, which dominates the closed-system vaping market and already has stopped making most flavored products, and a handful of other large makers of cartridge-based products are expected to file applications seeking so-called premarket approval of their products by May 12.

For the first time, vape companies will have to provide scientific evidence to support what they have claimed all along — that their products are safe and effective at helping adults quit combustible cigarettes.

But for the hundreds of small manufacturers whose products line the shelves at Capital Vape Supply and other tobacco and vaping stores nationwide, it is not financially feasible to file hefty applications for the dozens of flavored products they make, Conley said.

Beyond Bans

In the District of Columbia, a bill before the City Council would prohibit vape shops less than a quarter mile from a middle school. Another bill would require adults to have a prescription for vaping products, after the FDA approves vaping for smoking cessation.

In addition, anti-tobacco advocates are calling for tax hikes on vaping products, just as they have for cigarettes. Massachusetts in November raised its excise tax on retail sales of vaping products to 75%.

Minnesota’s retail tax is 95% and the District of Columbia’s is 96%. Vermont last year added a 92% tax on wholesale vaping products.

Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said his organization recommends that states enact a full complement of vaping restrictions, starting with flavor bans, tax hikes and inclusion of vaping in existing restrictions on indoor and outdoor nonsmoking areas.

“But it’s not a matter of raising awareness on the issue or twisting arms,” he said. Nearly all states, including those with Republican majorities, are seeking advice on how to quell runaway adolescent vaping, he said. “State officials are very interested and engaged on the issue. They’re ready to act.”

“The whole idea is to get away from cigarettes, so the last thing you want is a nasty-tasting imitation tobacco flavor and a harsh burn on the back of your throat.”

Gregory Conley, president American Vaping Association

The Arlington, Virginia-based association also advises states to consider limits on the concentration of nicotine in vaping products to reduce the risk of addiction.

Vaping cartridges made for Juul contain roughly 5% nicotine, compared with much lower concentrations in refillable tank systems. Newer disposable e-cigarettes tout the highest concentration yet at roughly 6%.

Still, traditional cigarettes deliver nicotine to the brain in its most addictive form, according to Truth Initiative, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit public health group that advocates for an end to tobacco use.

Harm Reduction

Some researchers and advocates who consider nicotine vaping an effective method of quitting cigarettes say the groundswell of new taxes, flavor bans, zoning regulations and other restrictions could do more harm than good.

Vaping nicotine is an effective means for the nation’s nearly 40 million smokers to quit and is far safer than smoking, said David Abrams, professor of social and behavioral sciences at New York University and former director of the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at the National Institutes of Health.

In the United Kingdom, where e-cigarette products are highly regulated by a health authority similar to the FDA, products are tested for safety before entering the market and nicotine concentrations are limited to 2%.

Although most U.S. public health experts recommend limits on nicotine concentrations in e-cigarettes to lessen the risk of addiction, Abrams disagrees. Whatever nicotine level is needed to attract cigarette smokers to vaping should be allowed, he said, since vaping is safer than smoking.

In the December issue of Science Magazine, he and four other researchers cautioned federal, state and local policymakers to ensure that the vaping regulations they enact are proportionate to the risk of vaping compared with smoking.

A Health Scare

Many of the new and proposed state and local vaping restrictions were triggered by the lung illness that has affected more than 2,600 people in all 50 states. Despite the CDC’s finding that the illness was tied to THC vaping, it heightened public awareness that unknown harms could result from any type of vaping.

“The pulmonary injury opened people’s eyes to the fact that anything you inhale into your lungs could be a problem,” Plescia said. He cited a December study by researchers at the University of California-San Francisco that found people who used e-cigarettes were at a somewhat higher risk of developing respiratory diseases from the chemicals used in the vaping fluids, including some flavorings.

In New York, state Rep. Linda Rosenthal, a Democrat, didn’t need convincing.

She said she was suspicious of e-cigarettes from the beginning. In 2010, she sponsored a bill that would have outlawed the sale of all e-cigarettes and vaping devices in the state until the FDA approved them.

“Somehow, I just knew,” Rosenthal said in an interview with Stateline. “At the time, most e-cigarettes were made in China and no one knew what was in them. We should know what’s in a product before we put it into our bodies.”

A former smoker, Rosenthal said she wasn’t concerned about adult smokers who claimed they needed flavored e-cigarettes to quit. “There are other methods people can use to quit, including talk therapies, the patch and gum.”

As for the stores that sell them, she said, “selling poisons to kids isn’t a very good business model.”

Earlier this month, the New York Supreme Court overturned a temporary statewide ban on flavored vaping products ordered by Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo in September. This month, in his State of the State address, Cuomo saidhe plans to ban all vaping flavors and ads directed at youth.

Within days, Rosenthal held a news conference to rally support for a pair of bills that would eliminate the sale of flavored vaping products and menthol-flavored cigarettes. Despite stiff opposition from the vaping industry, Rosenthal said she expects her bill to pass before the end of this month.

Adults Only

Advocates for vapers who are trying to quit smoking explain that flavors are essential.

“The whole idea is to get away from cigarettes, so the last thing you want is a nasty-tasting imitation tobacco flavor and a harsh burn on the back of your throat,” Conley said. The flavors are designed to be so appealing to adults that they never want to return to cigarettes, he said.

On a mild January afternoon, a steady stream of customers stepped into Gibson’s cozy store from the bustling sidewalks of the historic U Street neighborhood in D.C. Some were first-timers getting started on their New Year’s resolution to quit smoking. Most were regulars picking up fresh supplies or replacement parts.

The first thing Gibson tells his customers is that the lung illness was caused by THC — not nicotine. He shows them a notice from the CDC listing the offending THC products. None is available in his shop, he tells them. They nod in understanding.

For them, the lung scare is over and they’re back to vaping their favorite flavors: Paradox on Ice, Black Note Prelude and Dinner Lady Lemon Tart. Gibson explains that the flavors aren’t all that different from the Watermelon, Strawberry Milk and Mint flavors adolescents say they prefer in Juuls. They just have grown-up names.

Stateline is an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy. Since its founding in 1998, Stateline has maintained a commitment to the highest standards of non-partisanship, objectivity, and integrity. Its team of veteran journalists combines original reporting with a roundup of the latest news from sources around the country. Stateline focuses on four topics that are key to state policy: fiscal and economic issues, health care, demographics, and the business of government.