Rural America’s Health Crisis Seizes States’ Attention

By Michael Ollove, Stateline

Dr. George Pink is a professor who studies rural health, not a doctor who tries to provide it. For the sake of his own blood pressure, he’s grateful.

“Not a day doesn’t go by that I don’t thank God I’m an academic and not the CEO of a rural hospital,” Pink, a health policy professor and deputy director of the rural research program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said recently. “Recruiting providers, finding money, dealing with payers and lawsuits, dealing with the poor health outcomes, opioid addiction.”

It’s a lot.

Rural residents are in poorer health than those living elsewhere and have less access to treatment, partly because so many rural hospitals and health clinics have shuttered in recent years. As state legislatures begin their 2020 sessions, many lawmakers are struggling to find answers.

Brock Slabach, senior vice president of the nonprofit National Rural Health Association, said big ideas are needed to truly change the trajectory of rural health. The good news is that because of scale, rural areas are promising places to test out innovations in the delivery and financing of health care.

“They have defined populations and identifiable characteristics,” said Slabach, who used to be an administrator at a rural hospital in Mississippi. “That means when you are trying an intervention, you can see whether it’s working without all the variables you might have in urban areas. In that way, rural areas are the perfect laboratories.”

“But,” he added, “We don’t have the luxury of having years to spend finding solutions.”

While the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion brought health insurance to millions more Americans, including many rural residents, it has not ended many of the health care problems in rural areas: disparities in health outcomes, lack of access and an insufficient number of providers.

Many states are focused on making improvements, both large and small, to address the deficiencies. Among the ideas: creating private-public partnerships to increase access to care, sending mobile medical units into remote areas, expanding telemedicine and encouraging young people in rural communities to go into health professions.

Initiatives also are underway in several conservative states this year to join the 36 states that have expanded Medicaid, which would increase coverage in rural areas and increase revenue to rural hospitals.

Some states are trying to help rural hospitals deliver preventive care and chronic illness management beyond their walls, improving the collective health of the community while reducing health care costs.

Pennsylvania, for example, is engaged in what Slabach describes as “the boldest” state rural health initiative in the country. Other states are watching closely.

Called the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, it prospectively guarantees its 13 participating rural hospitals the revenue they will receive in the coming year.

The idea is that by giving hospitals certainty about their budgets, hospitals can focus on preventive care and chronic illness treatment in the community, said Dr. Rachel Levine, the Pennsylvania secretary of health. The model rewards the hospitals for keeping patients healthy and out of the hospital.

“Over time the idea is to devote more resources to population health measures and put less emphasis on trying to fill their beds,” Levine said.

One participant, Endless Mountains Health Systems, is deploying its personnel in new ways, said CEO Loren Stone, by monitoring patients in their homes, helping them with transportation to medical appointments and providing health education to cardiopulmonary patients and soon, he hopes, to patients with diabetes and heart disease.

Why the Disparity?

By most measures, the health of those living in rural areas is significantly worse than elsewhere. Mortality rates for the five leading causes of death — heart disease, cancer, unintentional injury, low respiratory disease and stroke — are all higher in rural areas, as is the overall mortality rate. And the gap is growing.

The suicide rate is higher in rural counties. Although the overall rate of death from drug overdoses is higher in urban areas than in rural ones, the reverse is true for certain drugs such as oxycodone and methamphetamines. Also, women in rural areas are more likely to die from overdoses than those in cities.

Health policy analysts cite multiple reasons for the rural disparities: poverty, and therefore less access to both health insurance and nutritious foods; higher rates of smoking, especially among young people; higher rates of obesity; and lower rates of exercise.

A contributing factor is the notoriously hard time rural areas have attracting and keeping medical professionals. Nearly 80% of rural counties are short on primary care doctors, and 9% have none, according to the National Rural Health Association’s Policy Institute.

“Many people have to travel 100 miles or more for specialty services,” said Oklahoma Commissioner of Health Gary Cox, adding that he hopes to develop a state fleet of rural mobile health clinics with help from a private partner.

The shortage of providers is likely to only get worse. More than 25% of primary care physicians in rural areas are 60 or older, compared with 18% in urban areas, according to a 2019 article in the New England Journal of Medicine. Few clamor to replace them.

“It is an unsustainable situation,” said Ann Peton, director of the National Center for Rural Health Works, a research organization in Blacksburg, Virginia.

Peton said that rural areas are trying to recruit health professionals from other regions and persuade local high school and college students to stay nearby and work in health professions.

Preserving Rural Hospitals

One of the main pillars in rural health also is in extreme peril.

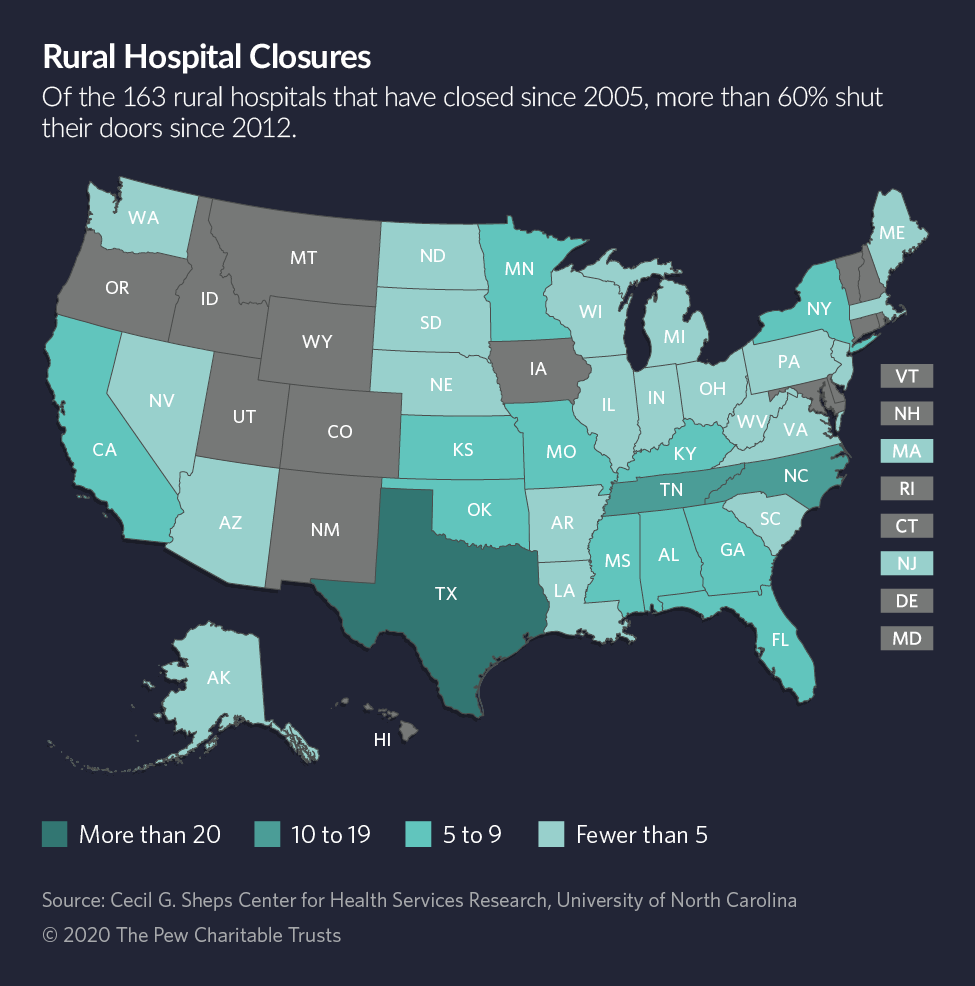

Since 2005, at least 163 rural hospitals have closed, more than 60% of them since 2012. Nineteen rural hospitals closed in 2019, the most in a year, according to Pink’s Rural Health Research Program at UNC-Chapel Hill, which tracks the rural hospital closures.

Rural health clinics are faltering too. Peton’s center reports that 388 clinics closed between 2012 and 2018, which left 4,245 in operation.

In Ashland, Kentucky, last week, Bon Secours Health Systems announced it was shutting Our Lady of Bellefonte Hospital, a 214-bed hospital. An estimated 1,000 people will lose their jobs. If history is a guide, the closure will hurt surrounding businesses and decrease local tax revenue.

About 2,200 rural hospitals are in business today, according to statistics from the Sheps Center for Health Services Research at UNC-Chapel Hill, but most survive on the slimmest of operating margins. Michelle Mills, CEO of the nonprofit Colorado Rural Health Center, said 22 rural hospitals in her state are operating in the red, double the number from the year before.

Tim Putnam, CEO of Margaret Mary Health, a 25-bed rural hospital and health system in southeastern Indiana, noted that rural hospitals like his serve populations that are older, poorer and sicker than urban ones. More patients rely on Medicare and Medicaid, public health plans respectively for the elderly and the poor, which reimburse at rates that usually do not cover expenses.

“Very few businesses would survive if they were getting back only 90 cents on the dollar,” said Stone, the Endless Mountains CEO in Pennsylvania. “We don’t get enough from commercial payers to bring us into profitability.”

His hospital, he said, has been operating at a loss since 2013.

For many states, Medicaid expansion has meant that medical providers are compensated for treating patients who might otherwise be uninsured. A 2018 study in the journal Health Affairs linked Medicaid expansion to improved financial performances for rural hospitals and lower likelihood of closures.

Serious efforts are underway in Kansas, Missouri, North Carolina and Oklahoma to expand Medicaid. Proponents in all those states cite the jeopardy faced by their rural hospitals as one of the main justifications for expansion.

But, as Stone said, expansion itself is not the salvation for rural hospitals. Substantial reimbursement is better than none, but he said that the low reimbursement paid by Medicaid still leaves his hospital with debt.

Similarly, he said, the ACA has not entirely been a financial blessing for rural hospitals. In addition to Medicaid expansion, the ACA provides affordable commercial health insurance through its exchanges, but many of those with modest incomes buy high-deductible plans that carry lower premiums. When patients can’t afford to pay those deductibles, rural hospitals end up with no payment for their services, he said.

Obstacles in Telemedicine

To reach rural residents, most states — especially those in the Northwest, Southwest and Northeast — have relaxed rules to give nurse practitioners, physician assistants and other medical professionals more authority to provide care that once was the purview of physicians. And most states allow Medicaid to reimburse services provided through telemedicine. But barriers remain.

For instance, Medicare limits reimbursement for telehealth in rural health clinics and federally qualified health centers, said Mei Wa Kwong, executive director of the Center for Connected Health Policy, a nonprofit in Sacramento, California, that promotes telemedicine. A measure to liberalize the law was introduced in the U.S. Senate last year, but it hasn’t advanced.

“Policy tends to lag behind the technology,” Kwong said.

The lack of broadband also hinders telemedicine in many areas of the country, she said. “The last thing you want is buffering or pixelating in the middle of a telehealth exam. That happens, and you’re just not going to want to use it.”

A number of states are aggressively seeking to expand their broadband, including in Minnesota, where last week Democratic Gov. Tim Walz announced $23 millionin grants to expand high-speed broadband to unserved and underserved areas.

‘Game Changer’

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services supports the Pennsylvania experiment. It also has invested in another multiyear Medicare project geared toward rural areas.

It gave $96 million in loans to help establish rural health networks called accountable care organizations. Their purpose is to concentrate on the delivery of care in a way that also emphasizes preventive care and management of chronic diseases to avoid costly hospitalizations and ultimately reduce health costs.

Much of the invested dollars went toward creating data and analytics to help providers achieve better health outcomes at lower costs. The model involved 47 accountable care organizations in 37 states.

The results have been promising, saving Medicare $262 million and cutting the numbers of hospitalizations, readmissions and emergency room visits.

“For us, it has been a game changer,” said Patricia Schou, executive director of the Illinois Critical Access Hospital Network, an organization of 57 rural hospitals in the state. The analytics, she said, have greatly enhanced providers’ ability to improve patient care and identify problem areas and correct them.

Seema Verma, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ administrator, has promised to introduce more payment changes to bolster rural health.

In Michigan, one Republican senator has a different idea for helping small rural hospitals: exempting them from some state regulation and oversight. State Sen. Curtis VanderWall’s seven-bill package would relax state rules regarding psychiatric beds, helicopter ambulances and some heart procedures.

VanderWall also wants to allow rural hospitals with fewer than 25 beds to expand or provide new services without state approval.

VanderWall said the changes, which are backed by Americans for Prosperity, the conservative group founded by the Koch brothers, would reduce costs by eliminating red tape. But the Michigan Health and Hospital Association opposes some features in the package, arguing it could lead to redundant services among hospitals, higher overall health care costs and reduced quality of care.

Many states are trying to make targeted improvements. Colorado allows paramedics with special training to make calls in rural areas to monitor patients and make sure they are taking medications properly. Cox, Oklahoma’s health commissioner, said his department identified $9 million in administrative savings, some of which he is using to raise the salaries of public health nurses working in rural areas.

In South Dakota, Republican Gov. Kristi Noem said in her State of the State address this month that she would soon announce a five-year plan to reduce suicides in the largely rural state.

In several states — including, Idaho, Oregon, Vermont, Washington and Texas — programs extend telemedicine to provide mental health services to young people, veterans and seniors. New mental health outreach programs also are underway in Michigan, Pennsylvania and North Dakota.

In Louisiana, Dr. Alexander Billioux, an assistant state health secretary, noted help the state provides rural health clinics to modernize information systems

Still, Billioux acknowledged, all the major health changes of the past few years, including passage of the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion, have not done nearly enough to improve the crisis in health afflicting rural America.

“In terms of trying to improve the delivery of care while reducing costs, it seems to me that we have the greatest opportunity in rural areas,” he said. “We’ve seen concerted interest, but we need to go beyond that now.”

Stateline is an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy. Since its founding in 1998, Stateline has maintained a commitment to the highest standards of non-partisanship, objectivity, and integrity. Its team of veteran journalists combines original reporting with a roundup of the latest news from sources around the country. Stateline focuses on four topics that are key to state policy: fiscal and economic issues, health care, demographics, and the business of government.