What a smoky bar can teach us about the ‘6-foot rule’ during the COVID-19 pandemic

Byron Erath, Clarkson University; Andrea Ferro, Clarkson University; Goodarz Ahmadi, Clarkson University, and Suresh Dhaniyala, Clarkson University

When people envision social distancing, they typically think about the “6-foot rule.”

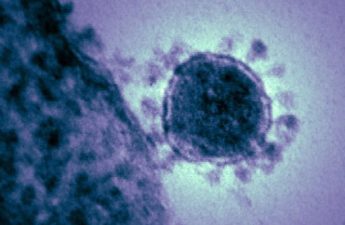

It’s true that staying 6 feet from other people can reduce the chance of a coronavirus-laden respiratory droplet landing in your eyes, nose or mouth when someone coughs. Most of these droplets are too tiny to see, and people are expelling them into the air all the time – when they shout, talk or even just breathe.

But the 6-foot rule doesn’t account for all risks, particularly indoors.

Think about walking into a room where someone is smoking a cigarette. The closer you are to the cigarette, the stronger the smell – and the more smoke you’re inhaling. That smoke also lingers in the air. Over time, it won’t matter where you are in the room; the smoke will be everywhere.

Cigarette smoke comprises particles that are similar in size to the smaller respiratory droplets expelled by humans – the ones that linger in the air the longest. While it’s not a perfect analogy, picturing how cigarette smoke moves through different environments, both indoors and outdoors, can help in visualizing how virus-laden droplets circulate in the air.

As professors who study fluid dynamics and aerosols, we have been exploring how COVID-19 circulates and the risks it creates. The 6-foot rule is a good benchmark that’s easy to remember, but it’s important to understand its limitations.

Aerosols and an 86-year-old rule

The 6-foot rule goes back to a paper published in 1934 by William F. Wells, who was studying how tuberculosis spreads. Wells estimated that small respiratory droplets evaporate quickly, while large ones rapidly fall to the ground, following a ballistic-like trajectory. He found that the farthest any droplets traveled before either settling or evaporating was about 6 feet.

While that distance can reduce exposure, it does not provide a complete picture of infection risk from the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

When people exhale, they expel respiratory droplets with a wide range of sizes. Most are smaller than 10 microns in diameter. These can quickly decrease to approximately 40% of their original diameter, or smaller, due to evaporation.

The droplets will not completely evaporate, however. This is because they consist of both water and organic matter, potentially including the SARS-CoV-2 virus. These tiny droplets stay suspended in the air for minutes to hours, posing a risk to anyone who comes into contact with them. When suspended in the air, these droplets are commonly referred to as aerosols.

Indoors or outdoors: Ventilation matters

Infection risk is highest right next to a person who has the virus and decreases with distance. However, the way respiratory droplets mix in the air and the resulting concentration influence the distance needed to safely avoid exposure.

Outdoors, the combination of physical distancing and face coverings provides excellent protection against virus transmission. Think again of being near a smoker. Smoke can be carried by the wind much farther than 6 feet, but high concentrations of smoke do not usually build up outdoors because the smoke is quickly diluted by the large volume of air. A highly effective strategy to avoid breathing smoke is to avoid being directly downwind of the smoker. This is also true for respiratory droplets.

Indoors, the picture is very different.

Very light room air currents from fans and ventilation units can transport respiratory droplets over distances much greater than 6 feet. However, unlike being outdoors, most indoor spaces have poor ventilation. That allows the concentration of small airborne respiratory droplets to build up over time, reaching all corners of a room.

When indoors, the infection risk depends on variables such as the number of people in the room, the size of the room and the ventilation rate. Speaking loudly, yelling or singing can also generate much larger concentrations of droplets, greatly increasing the associated infection risk.

It’s not surprising that most “superspreader” events that have infected large numbers of people involved indoor gatherings, including business conferences, crowded bars, a funeral and choir practice.

Strategies for staying safe

In pre-COVID-19 times, few people worried about respiratory infection from small virus-laden droplets accumulating indoors because their virus load was usually too low to cause an infection.

With SARS-CoV-2, the situation is different. Studies have shown that COVID-19-positive patients, even those who are asymptomatic, carry a high load of the virus in their oral fluids. When airborne droplets emitted by these patients during conversation, singing and so on are inhaled, respiratory infection is possible.

There is no safe distance in a poorly ventilated room, unfortunately. Good ventilation and filtration strategies that bring in fresh air are critical to reduce aerosol concentration levels, just as opening windows can clear out a smoke-filled room.

In addition, masks or face coverings should be worn at all times in public indoor environments. They both reduce the concentration of respiratory droplets being expelled into the room and provide some protection against inhaling infectious aerosols.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Finally, because the risk of infection increases with exposure time, limiting the amount of time spent inside public spaces is also important.

The 6-foot social distancing guideline is a critical tool for combating the spread of COVID-19. However, as more activities move indoors with the arrival of cooler weather this fall, implementing safeguards, including those you might use to avoid inhaling cigarette smoke, will be essential.

Byron Erath, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Clarkson University; Andrea Ferro, Professor of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Clarkson University; Goodarz Ahmadi, Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Clarkson University, and Suresh Dhaniyala, Bayard D. Clarkson Distinguished Professor of Mechanical and Aeronautical Engineering, Clarkson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.