Patients admitted to the hospital with higher levels of the COVID-19 virus, SARS-CoV-2, were more than four times more likely to die in the subsequent 30 days than were those with lower levels of the virus, according to a finding by researchers in laboratory medicine and pathology at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

On the other hand, patients who had generated antibodies against the virus by the time of admission tended to have lower levels of virus. They also had a 30-day risk of death that was approximately half that of patients who had not generated antibodies, although this result was not as statistically significant as the association between viral levels and mortality.

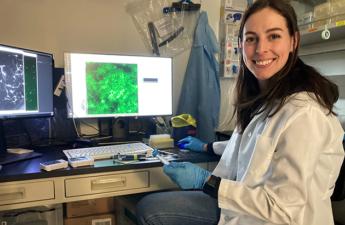

“Currently, SARS-CoV-2 tests have generally only been authorized to tell if the virus is present but not for determining the quantity of virus present,” said Dr. Alex Greninger, a assistant professor and assistant director of the UW Medicine Clinical Virology Laboratory. “Our findings suggest tests that measuring the amount of virus – the viral load – can help doctors identify those admitted to the hospital who are at highest risk of serious disease and need special attention.”

The researchers’ reported findings appear in the journal Open Forum Infectious Disease.

In the study, the researchers identified patients admitted to UW Medicine’s Northwest campus whose SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swabs tested positive. The researchers also tested serum and blood samples from 245 of these patients for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, and reviewed medical records to determine the date the patients developed symptoms and their subsequent clinical outcomes. The antibody test looked for anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid IgG, an antibody that targets a key viral protein.

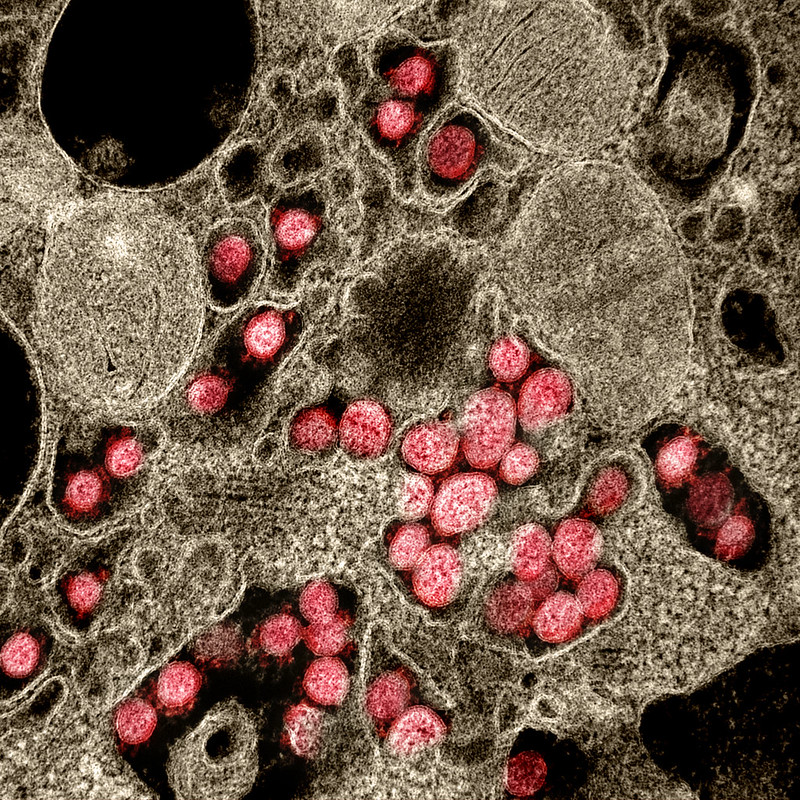

The levels of virus were determined by a process called qRT-PCR, for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. In this process, a segment of the coronavirus genome, which is made of RNA, is converted into DNA. This process is called reverse transcription. The DNA copies are then doubled again and again through repeated cycles of the polymerase chain reaction. This process can generate millions or billions of copies of a single strand of DNA, thereby enabling the detection of minute amounts of viral RNA in a sample.

The researchers found that patients who, upon hospital admission, had virus levels high enough that the PCR test turned positive in less than 22 cycles had a four-fold higher risk of dying in the next 30 days than patients whose viral levels required more than 22 cycles to detect the virus.

In the case of antibodies, patients who had already begun making the anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid IgG against the virus upon hospital admission tended to have a lower viral load and also appeared to do better. Those patients were about half as likely to die in the next 30 days than those who did not yet have antibodies.

Because of the relatively small number of patients in the study, the survival benefit seen with the presence of antibodies was not statistically significant, the researchers noted. Not surprisingly, the presence of antibodies was associated with a lower viral load.

“Our findings provide further support for the use of quantitative viral-load assessment and antibody testing in managing patients, especially on hospital admission,” said Dr. Andrew Bryan, assistant director of clinical microbiology and medical director of the clinical laboratory at UW Medical Center – Northwest.

This work was supported by the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology at the University of Washington School of Medicine.