By Korydon Smith, University at Buffalo; Kelly Hayes McAlonie, University at Buffalo, and Rebecca Rotundo, University at Buffalo

While the pandemic has caused thousands of small businesses to temporarily close or shutter for good, the disappearance of the corner coffee shop means more than lost wages.

It also represents a collective loss of creativity.

Researchers have shown how creative thinking can be cultivated by simple habits like exercise, sleep and reading. But another catalyst is unplanned interactions with close friends, casual acquaintances and complete strangers. With the closure of coffee shops – not to mention places like bars, libraries, gyms and museums – these opportunities vanish.

Of course, not all chance meetings result in brilliant ideas. Yet as we bounce from place to place, each brief social encounter plants a small seed that can gel into a new idea or inspiration.

By missing out on chance meetings and observations that nudge our curiosity and jolt “a-ha!” moments, new ideas, big and small, go undiscovered.

It’s not the caffeine, it’s the people

Famous artists, novelists and scientists are often seen as if their ideas and work come from a singular mind. But this is misleading. The ideas of even the most reclusive of poets, mathematicians or theologians are part of larger conversations among peers, or are reactions and responses to the world.

As author Steven Johnson wrote in “Where Good Ideas Come From,” the “trick to having good ideas is not to sit around in glorious isolation and try to think big thoughts.” Instead, he recommends that we “go for a walk,” “embrace serendipity” and “frequent coffeehouses and other liquid networks.”

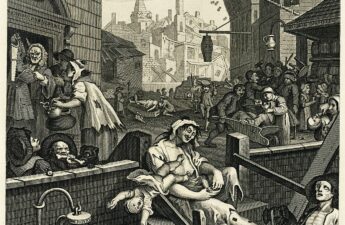

Just as today’s freelance writers might use coffee shops as a second office, it was the tea- and coffeehouses of London in the 18th century that spurred the Age of Enlightenment. Then, as now, people intuitively knew they were “more productive or more creative when working from coffee shops,” according to David Burkus, author of “The Myths of Creativity.” As research shows, it’s not the caffeine; it’s the people. Simply being around other people who are working can motivate us to do the same.

In other words, creativity is social.

It’s also contextual. The built environment plays a hidden but crucial role. Architectural researchers in the U.K., for instance, found that classroom design impacts the speed at which students learn. They found that classroom features, such as furniture and lighting, have as much impact on learning as teachers. Similar aspects of cafe design can enhance creativity.

Designing for creativity

Buildings influence a wide range of human functions. Temperature and humidity, for example, affect our ability to concentrate. Daylighting is positively linked to productivity, stress management and immune functions. And air quality, determined by HVAC systems as well as the chemical composition of furnishings and interior materials like carpet, affects both respiratory and mental health. Architectural design has even been connected to happiness.

Likewise, a well-designed coffee shop can facilitate creativity – where the unplanned friction between people can ignite sparks of innovation.

Two newly completed coffee shops, the Kilogram Coffee Shop in Indonesia and Buckminster’s Cat Cafe in Buffalo, New York, were designed with this kind of interactivity in mind.

Each has open, horizontal layouts that actually encourage congestion, which fosters chance encounters. Lightweight and geometric furniture enables occupants to rearrange seating and accommodate groups of various size, such as when a friend unexpectedly arrives. There are views outside, which promote calmness and offer more opportunities to daydream. And there is a moderate level of ambient noise – not too high or low – which induces cognitive disfluency, a state of deep, reflective thinking.

Restoring the soul of the coffee shop

Of course, not all coffee shops have closed. Many shops have reduced indoor seating capacity, limited patrons to exterior seating or have restricted services to takeout only as a means to stay open. All of them have faced the difficult task of implementing safeguards while retaining the atmosphere of their establishments. Some design elements, like lighting, can easily be retained amidst social distancing and other safety measures. Others, like movable seating for collaboration, are harder to achieve safely.

While these tweaks allow businesses to stay open and ensure the safety of customers, they sap spaces of their souls.

Philosopher Michel de Certeau said that the spaces we occupy are a backdrop on which the “ensemble of possibilities” and “improvisation” of everyday life occur.

When social life fully transitions into the digital realm, these opportunities become limited. Conversations become prearranged, while the side chats that take place before or after a meeting or event have been quashed. In video meetings, participants speak to either the whole room or no one.

For cafe owners, employees and customers, the post-pandemic era can’t come soon enough. After all, while customers ostensibly stop by their local coffee shop for a jolt of caffeine, the true draw of the place is in its haptic and hectic spirit.

Korydon Smith, Professor of Architecture and Associate Director of Global Health Equity, University at Buffalo; Kelly Hayes McAlonie, Adjunct Instructor of Architecture, University at Buffalo, and Rebecca Rotundo, Associate Director of Instructional Design, University at Buffalo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.