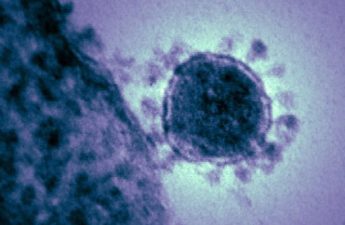

Image: Narender9 via Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0

Rajib Dasgupta, Jawaharlal Nehru University

India is in the grip of a massive second wave of COVID-19 infections, surpassing even the United States and Brazil in terms of new daily infections. The current spike came after a brief lull: daily new cases had fallen from 97,000 new cases per day in September 2020 to around 10,000 per day in January 2021. However, from the end of February, daily new cases began to rise sharply again, passing 100,000 a day, and now crossing the 200,000 mark.

Night curfews and weekend lockdowns have been reinstated in some states, such as Maharasthra (including the financial capital Mumbai). Health services and crematoriums are being overwhelmed, COVID test kits are in short supply, and wait times for results are increasing.

How has the pandemic been spreading?

Residents in slum areas and those without their own household toilet have been worst affected, implying poor sanitation and close living have contributed to the spread.

One word that has dominated discussions about why cases have increased again is laaparavaahee (in Hindi), or “negligence”. The negligence is made out to be the fault of individuals not wearing masks and social distancing, but that is only part of the story.

Negligence can be seen in the near-complete lack of regulation and its implementation wherever regulations did exist across workplaces and other public spaces. Religious, social and political congregations contributed directly through super-spreader events, but this still doesn’t explain the huge rise in cases.

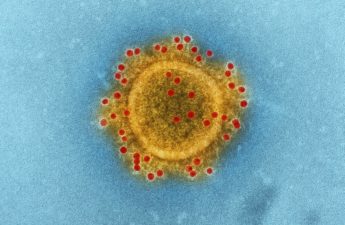

The second wave in India also coincides with the spread of the UK variant. A recent report found 81% of the latest 401 samples sent by the state of Punjab for genome sequencing were found to be the UK variant.

Studies have found this variant might be more capable of evading our immune systems, meaning there’s a greater chance previously infected people could be reinfected and immunised people could be infected.

A new double mutation is also circulating in India, and this too could be contributing to the rise in cases.

Low fatality rate?

In the first phase of the pandemic, India was lauded for its low COVID death rate (case fatality rate) of about 1.5%. However, The Lancet cautioned about the “dangers of false optimism” in its September 26 editorial on the Indian situation.

In a pandemic situation, the public health approach is usually to attribute a death with complex causes as being caused by the disease in question. In April 2020, the World Health Organization clarified how COVID deaths should be counted:

A death due to COVID-19 is defined for surveillance purposes as a death resulting from a clinically compatible illness, in a probable or confirmed COVID-19 case, unless there is a clear alternative cause of death that cannot be related to COVID disease (e.g. trauma)

It is unclear the extent to which the health authorities across the states of India were complying with this.

Many states have set up expert committees to re-examine and verify COVID-19 deaths after coming under criticism that reported death rates were not accurate. Many states made corrections in mortality figures, and the full extent of undercounting is being actively researched.

District-level mortality data, both in the first wave as well as in the current wave, confirm that the global case fatality rate of 3.4% was breached in several districts such as Maharashtra, Punjab and Gujarat. Case fatality rates in some of the worst-affected districts were above 5%, similar to the 5% mortality level in the US.

What are the challenges this time?

A majority of the cases and deaths (81%) are being reported from ten (of 28) states, including Punjab and Maharashtra. Five states (Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Kerala) account for more than 70% of active cases. But the infection seems to have moved out of bigger cities to smaller towns and suburbs with less health infrastructure.

Last year, the government’s pandemic control strategy included government staff from all departments (including non-health departments) contributing to COVID control activities, but these workers have now been moved back to their departments. This is likely to have an effect on testing, tracing and treating COVID cases. And health-care workers now have a vaccine rollout to contend with, as well as caring for the sick.

Read more: ‘How will we eat’? India’s coronavirus lockdown threatens millions with severe hardship

What now?

In early March the government declared we were in the endgame of the pandemic in India. But their optimism was clearly premature.

Despite an impressive 100 million-plus immunisations, barely 1% of the country’s population is currently protected with two doses of the vaccine. The India Task Force is worried that monthly vaccine supplies at the current capacity of 70 million to 80 million doses per month would “fall short by half” for the target of 150 million doses per month.

Strict, widespread lockdowns we have seen elsewhere in the world are not appropriate for all parts of India given their effect on the working poor. Until wider vaccination coverage is achieved, local containment measures will have to be strengthened. This includes strict perimeter control to ensure there is no movement of people in or out of zones with local outbreaks, intensive house-to-house surveillance to ensure compliance with stay-at-home orders where they are in place, contact tracing, and widespread testing.

It should go without saying large congregations such as political rallies and religious festivals should not be taking place, and yet they have been.

Strong leadership and decentralised strategies with a focus on local restrictions is what we need until we can get more vaccines into people’s arms.

Rajib Dasgupta, Chairperson, Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health,

Jawaharlal Nehru University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.