Adrian Raftery, University of Washington

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced in May 2021 that the nation’s total fertility rate had reached 1.64 children per woman in 2020, dropping 4% from 2019, a record low for the nation.

The news led to many stories about a “baby bust” harming the country. The fear is that if the trend continues, the nation’s population may age and that will lead to difficulties in funding entitlements like Social Security and Medicaid for seniors in the future.

But as a statistician and sociologist who collaborates with the United Nations Population Division to develop new statistical population forecasting methods, I’m not yet calling this a crisis. In fact, America’s 2020 birth rate is in line with trends going back over 40 years. Similar trends have been observed in most of the U.S.‘s peer countries.

The other reason this is not a crisis, at least not yet, is that America’s historically high immigration rates have put the country in a demographic sweet spot relative to other developed countries like Germany and Japan.

But that could change. A recent dramatic decline in immigration is now putting the country’s demographic advantage at risk.

Falling immigration may be America’s real demographic crisis, not the dip in birth rates.

A predictable change

Most countries have experienced part or all of a fertility transition.

Fertility transitions occur when fertility falls from a high level – typical of agricultural societies – to a low level, more common in industrialized countries. This transition is due to falling mortality, more education for women, the increasing cost of raising children and other reasons.

In 1800, American women on average gave birth to seven children. The fertility rate decreased steadily, falling to just 1.74 children per woman in 1976, marking the end of America’s fertility transition. This is the point after which fertility no longer declined systematically, but instead began to fluctuate.

Birth rates have slightly fluctuated up and down in the 45 years since, rising to 2.11 in 2007. This was unusually high for a country that has made its fertility transition, and put the U.S. birth rate briefly at the top of developed countries.

A decline soon followed. The U.S. birth rate dropped incrementally from 2007 to 2020, at an average rate of about 2% per year. 2020’s decline was in line with this, and indeed was slower than some previous declines, such as the ones in 2009 and 2010. It put the U.S. on par with its peer nations, below the U.K. and France, but above Canada and Germany.

Using the methods I’ve helped develop, in 2019 the U.N. forecast a continuing drop in the global birth rate for the period from 2020 to 2025. This methodology also forecast that the overall world population will continue to rise over the 21st century.

The ideal situation for a country is steady, manageable population growth, which tends to go in tandem with a dynamic labor market and adequate provision for seniors, through entitlement programs or care by younger family members. In contrast, countries with declining populations face labor shortages and squeezes on provisions for seniors. At the other extreme, countries with very fast population growth can face massive youth unemployment and other problems.

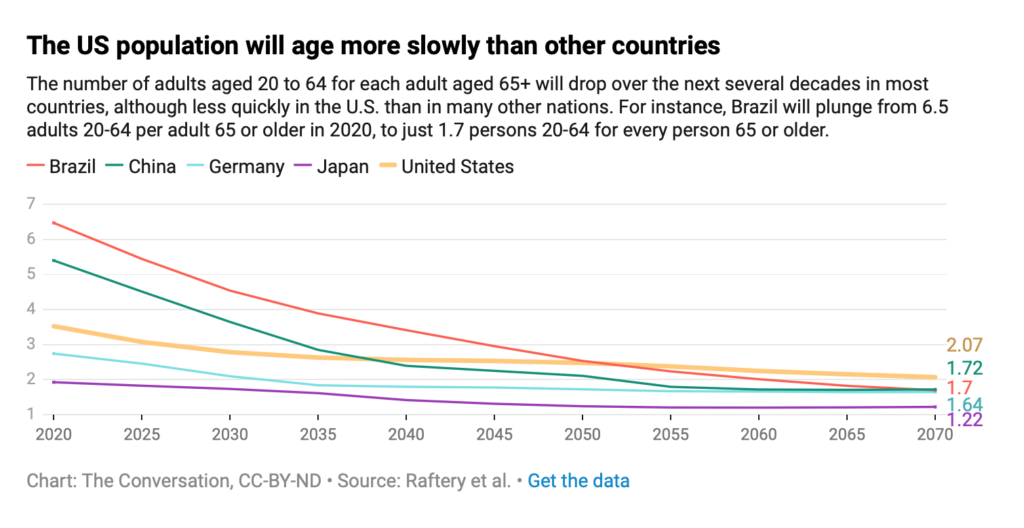

Many countries that are peers with the U.S. now face brutally sharp declines in the number of working-age people for every senior within the next 20 years. For example, by 2040, Germany and Japan will have fewer than two working-age adults for every retired adult. In China, the ratio will go down from 5.4 workers per aged adult now to 1.7 in the next 50 years.

By comparison, the worker-to-senior ratio in the U.S. will also decrease, but more slowly, from 3.5 in 2020 to 2.1 by 2070. By 2055, the U.S. will have more workers per retiree than even Brazil and China.

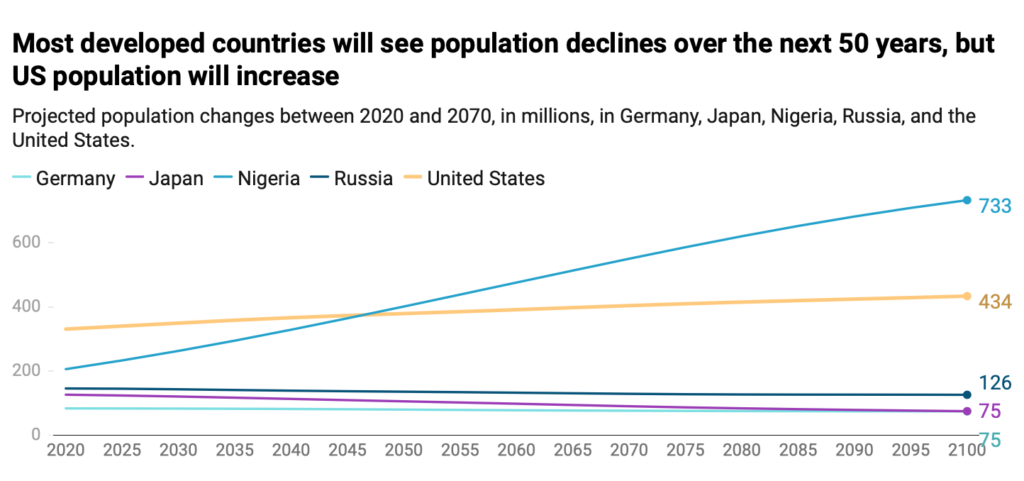

Germany, Japan and other nations face population declines, with Japan’s population projected to go down by a massive 40% by the end of the century. In Nigeria, on the other hand, the population is projected to more than triple, to over 700 million, because of the currently high fertility rate and young population.

In contrast, the U.S. population is projected to increase by 31% over the next 50 years, which is both manageable and good for the economy. This is slower than the growth of recent decades, but much better than the declines faced by peer industrialized nations.

The reason for this is immigration. The U.S. has had the most net immigration in the world for decades, and the projections are based on the assumption that this will continue.

Migrants tend to be young, and to work. They contribute to the economy and bring dynamism to the society, along with supporting existing retirees, reducing the burden on current workers.

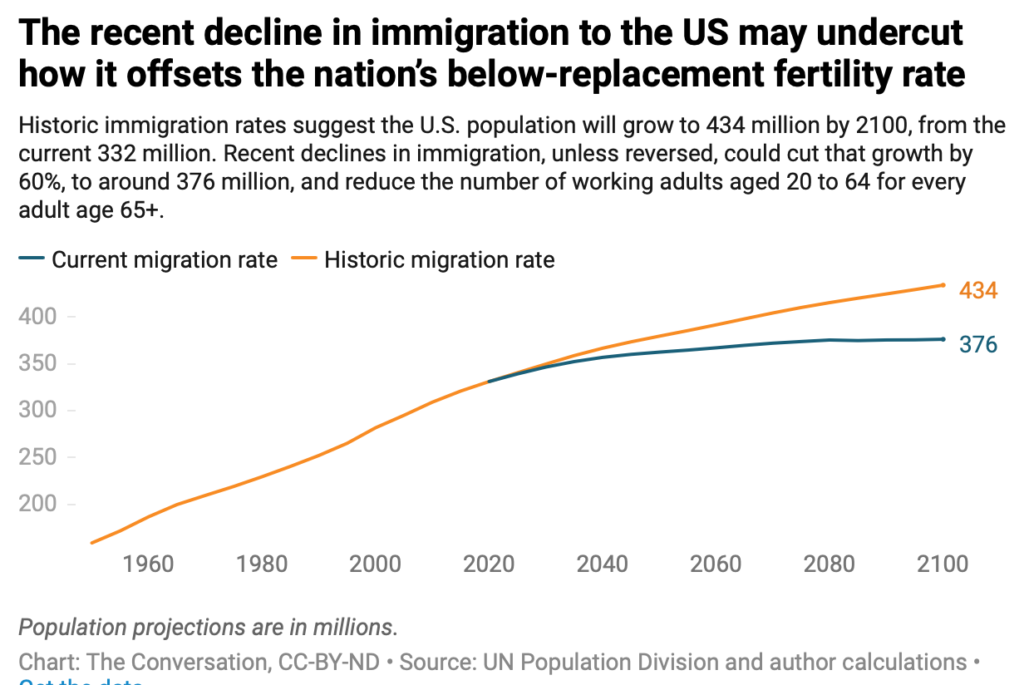

However, this source of demographic strength is at risk. Net migration into the U.S. declined by 40% from 2015 to 2019, likely at least in part because of unwelcoming government policies.

If this is not reversed, the country faces a demographic future more like that of Germany or even Japan, with a rapidly aging population and the economic and social problems that come with it. The jury is out on whether family-friendly social policies will have enough positive impact on fertility to compensate.

If U.S. net migration continues on its historical trend as forecast by the U.N., the U.S. population will continue to increase at a healthy pace for the rest of the century. In contrast, if U.S. net migration continues only at the much lower 2019 rate, population growth will grind almost to a halt by 2050, with about 60 million fewer people by 2100. The fall in migration would also accelerate the aging of the U.S. population, with 7% fewer workers per senior by 2060, leading to possible labor shortages and challenges in funding Social Security and Medicare.

While the biggest stream of immigrants is from Latin America, that is likely to decrease in the future given the declining fertility rates and aging populations there. In the longer term, more immigrants are likely to come from sub-Saharan Africa, and it will be important for America’s demographic future to attract, welcome and retain them.

Adrian Raftery, Boeing International Professor of Statistics and Sociology, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.