The Conversation Canada and McMaster University recently co-hosted a live event on vaccine hesitancy. Editor-in-Chief Scott White spoke with four researchers from McMaster: Medical doctor, educator and researcher Zain Chagla; immunologist Dawn Bowdish; Manali Mukherjee, an assistant professor in the division of respirology at McMaster’s department of medicine; political scientist Clifton van der Linden, who has been conducting ongoing public opinion surveys on COVID-19.

Viewers submitted questions to the panel. This is an edited excerpt from the discussion, but you can watch the entire event in the video below.

Scott White: How many of you have a vaccine hesitant person in your inner circle? What have you tried to say to them to persuade them that vaccines are safe?

Dawn Bowdish: All the good practices that I use with strangers, I have a hard time implementing with my own family. I think one of the important parts about vaccine hesitancy is it’s not my facts versus your facts and I have all the right facts and you have all the wrong facts, because people who are vaccine hesitant have lots of information, and there’s no metric to say that makes them feel that my information is better than theirs. So I feel like listening to people’s concerns and being really specific and not making judgment calls about what their concerns might be. Because to be honest, the vaccine hesitancy spectrum is huge. So where I have gone wrong with my own family is doing all the things that you shouldn’t do. I talked more than I listened. I threw scientific facts as opposed to listening to people’s stories and concerns. And I appealed to the authority. “I’ve got a PhD. I’ve been working on this for 20 plus years,” and that was a mistake. And so those are the things I would caution people against when you have your own conversations with your vaccine hesitant family members or friends.

Zain Chagla: We know from things like smoking cessation where the more times that conversation happens in a nonjudgmental and non-confrontational matter, it often ends up with the right outcome at the end of the day. So again, it’s not a conversation to win to the other side and get someone to the pharmacy that afternoon. It’s a conversation to start another conversation and start another conversation and keep going along those lines.

Scott White: Cliff, you’ve done a lot of work on taking the public pulse on this. What have you learned on trying to convince someone?

Clifton van der Linden: Certainly, no matter how we model the public opinion data coming in on attitudes towards COVID-19, when it comes to vaccine hesitancy, trust is really the major factor. I think we are in an era where there’s a real sense of anti-intellectualism that’s being cultivated in certain corners of the internet. I think the social media discourse has a huge role to play in the way that trust has eroded as a society. But there are factors in the way that government has conducted itself. There are factors in the bad faith in which certain public actors have conducted themselves. And so there are lots of reasons for mistrust at an institutional level. So I do think that trying to ground conversations with people we love in that framework of trust, knowing that we are concerned about them, that we’re approaching them not because we want to be right but because the consequences of them being wrong are so dire for themselves and for our families and loved ones.

Why are there such strong reactions against vaccines?

Scott White: One thing that’s always puzzled me is that there seems to be this really rabid reaction against vaccines, but not other medical procedures like surgery, which is far more invasive, or taking medicine. What is it about vaccines that really seems to cause this hesitancy or resistance?

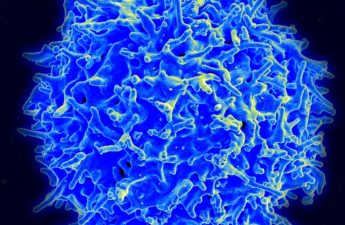

Dawn Bowdish: My belief is that it’s partly because it’s a needle and partly because there’s this big mystery about how the immune system works and how it (the vaccine) could be so powerful. The active ingredients in our current vaccines is like 10 micrograms. If you look in your medicine cabinet at your Tylenol, your Advil or whatever, you’ll see that we work in milligrams. But 10 micrograms, a thousand times less, has this incredible powerful effect to be able to create a whole immune response. The amount of stuff that’s in the vaccine is negligible. It’s nothing. But this incredibly powerful immune event, I think is a little bit humbling in some ways.

Clifton van der Linden: I think that especially in the last five or six years, we have been flooded with discussions of fake news, misinformation, disinformation. I mean, we are told not to trust what we hear from government, depending on who’s running government. The idea that you can trust one day and then not trust the next when there’s a change of party, it leaves people in the state of constant cynicism about the good faith I think particularly of elected officials, but also of government institutions in general. I think there’s a difference in Canada compared to countries like the U.S., where in Canada we do see that the public tends not to trust elected officials, but we still do have a lot of trust in our public health institutions in Canada.

The safety of vaccines that were developed so quickly

Scott White: At The Conversation, we’ve been running a series of articles about vaccine confidence and vaccine hesitancy and have been inviting questions from the public. And sort of one of the recurring questions that we get is that people seem to have trouble wrapping their head around the fact that the COVID vaccines have been developed so quickly and that scientists don’t know the long-term effects.

Dawn Bowdish: The apparent speed was based on decades of fundamental research. I love this as a story because often times as a university academic, the general public thinks we waste time working on things that are fundamentally unimportant. In fact, we did have mRNA based vaccines in the pipeline for many different infections. One of the beauties of the mRNA technology is that it’s fairly easy to alter. Many of the features of vaccination – the dosing intervals, the amount of doses, how we de develop things for kids and for adults and older people – are all based on decades and decades of experience.

Pregnancy and vaccines

Scott White: We get a lot of questions about the potential impact of vaccines on fertility. Zain, from a medical perspective, what are the dangers of not being vaccinated if you are pregnant?

Zain Chagla: Look, no one is going to deny that most people do get through their infections and don’t die. I think we know this very well, but it doesn’t say that everyone is safe. We do know that elderly people are much more at risk of complications. We know what people with comorbidities are in much more risk of complications. And we have seen young people, who despite looking great on paper, are sitting in our ICUs ventilated, because again, once this virus gets out of control, once the immune system gets super jacked up, it really can cause chaos. And we sometimes don’t know who is that person that it’s going to be chaotic in and not. Pregnant women, I think we’re recognizing much more are in that risk group now. And then we have seen some fairly sick pregnant women. They’re physiologically unwell. They’re obviously carrying a baby. The concerns of having severe COVID not only in the mother, but in the baby, are also a major issue. Unfortunately, we’ve had to deliver babies prematurely for the fact that it would spare the mother their lives more and then make their mother’s oxygenation better.

Dawn Bowdish: We don’t have a single example of a vaccine leading to long term fertility issues or leading to, I don’t even know what people are envisioning with the context of fertility, but the immune system attacking your ovaries or whatever. And in fact, all those mythologies I think were incredibly clever by the anti-vax group. Because if you’re a parent, what more do you want than grandchildren? And so what is going to trigger your emotional response and your desire to wait and to see more than that threat?

What is long COVID?

Scott White: Manali, you’ve not only researched long COVID, but you’re dealing with it personally. I’m not sure that people fully understand the term and the impact that it can have on your life. So can you tell us about that? And then also speak about the best way to avoid it.

Manali Mukherjee: A considerable proportion of people who have been infected with COVID-19, irrespective of how severe they were, whether they were in the hospital or whether they recover at home, they continue to have symptoms or actually develop new symptoms long after they have so-called recovered. So the public health gives you that call and tells you, “You know, you have recovered. If you’re feeling fine, go back to work.” But there are a number of people who still feel sick, who have lingering symptoms. These symptoms can range anywhere from chronic fatigue, sense of smell not being there, completely being distorted, having diffused pain, and of course all these can lead to anxiety, palpitations and cognitive impairment. So it’s a constellation of symptoms that’s kind of lingering. And none of these symptoms can be attributed to a clinical diagnosis that they either had before getting COVID. We are trying to look at what might be the reason behind it. I have reasons to believe that it’s deep seated within the immune system. I think that after having COVID, the immune system is still so hyper and it still thinks that the virus is possibly hiding somewhere or there is something still going on and the symptoms are a clinical manifestation of that misunderstanding that the immune system has. So that’s what we are trying to right now unravel and understand and makes sense.

Scott White: Who’s more susceptible to long COVID? Is it younger people? Older people? Do we know?

Manali Mukherjee: In my study, I’m seeing people from all age groups, all ethnicities coming in. Even asymptomatic people, people who have the infection, PCR positive test was in asymptomatic. Now they’re having symptoms. So really, we don’t know who’s going to get affected, why they’ll be affected. And worse, we just don’t know when this will stop or whether it will. What worries me right now is we don’t know much right now about the long COVID cases that we have from the original virus, the Wuhan virus to the alpha, beta, delta strains, how long COVID symptoms vary. And now the omicron has come in where we don’t know how it’s really going to be affecting our immune system given that it seems to have a higher transmissibility. And having been said, despite having a milder load, we don’t know how it’s going to really affect those with a longer COVID kind of situation. Will it affect more people with lingering, longer persisting symptoms than actually having a more severe acute infection phase? We don’t know. If you are vaccinated, there is data out there that it kind of reduces your long COVID symptoms. So if you are vaccinated and then still you get omicron, the logic tells me that your immune system might be a better streamlined, the way Dawn said, to handle that infection in a better mode as to not confuse it and make it more rowdier and lead to those lingering long COVID symptoms. So that is again another thing that tells me that vaccination and taking the boosters might actually be in our benefit as a society and community going towards natural immunity or herd immunity.

Natural immunity vs. vaccine immunity

Scott White: There’s been a lot of discussion about herd immunity and on social media, instant experts say natural immunity is better than being vaccinated. Dawn, tell us about herd immunity and natural immunity versus vaccinated – especially as we’re now dealing with the omicron variant.

Dawn Bowdish: Well, I mean, Manali just gave you an example of natural immunity, right? Long COVID is a natural immune response in some people. I don’t think there’s anything unnatural about a vaccine response. It’s giving your immune system the opportunity to work without distraction, right? So when you get infected with a virus, the virus doesn’t just say, “Oh, whoa. It was me. The immune system’s coming to get me.” It’s destroying tissues. The immune system in many cases is misdirecting and attacking those tissues. So some of the tissue damage we see is mediated by natural immunity, because it gets confused where there’s tissue damage in the context of infections. So natural immunity works sometimes, but vaccine immunity is natural immunity. It’s immunity working without distraction, letting the immune system do its thing without having this virus that’s fighting back and trying to thwart it. The thing about herd immunity is, let’s go back to a time before we had vaccines, antibiotics and doctors. One in three to one in five children died. There were more miscarriages, spontaneous abortions and babies born with severe complications because having an infection during pregnancy is problematic. Sure, if you were one of the lucky ones to survived your first birthday, you might have some level of protection until you got older or until you’ve had some immune compromising event or other illness. So a herd immune system gives a small percentage of the population a little bit of time to be protected from that. But as soon as a new baby’s born, a new pregnancy started, that susceptibility happens all over again. So the idea that we would just let a new virus run rampant in a population and take those risks to the young, the old, the random healthy adults is just cruel from my perspective. Really cruel. The best way for us to reach herd immunity is to get us all vaccinated.

Zain Chagla: Right now our health-care system is burned to a crisp. We can’t deal with our current caseloads because we have complex patients coming in every day. We have ICU beds that are still allotted for COVID patients and we have health-care workers that are burnt out and have left the profession and are not coming back. So there is a lot of worry in the coming weeks and months as this circulates, that we’re going to see health systems overload. We’re going to see a lot of people test positive regardless of the vaccine status. And we’re going to see a lot of isolation and complications from that. The good news out of all of this though, is boosters do seem to really change the dynamic of vaccines and offer higher level of protection. We’re getting better data by the day that really is suggesting this. And so, I think there is work being done right now across the country, in particular Ontario, to make sure people do have access to a booster shot when their time comes.

A lack of trust in expertise

Scott White: Some people don’t trust government. They don’t trust pharmaceutical companies. And although they may trust their personal doctor, they don’t trust intellectuals and they don’t trust people at universities. Why is that Cliff?

Clifton van der Linden: We’ve seen a rise in populism throughout western democracies. And along with that rising populism, we’ve seen an unprecedented strain of anti-intellectualism, rejection of science in ways that we have not seen in the post-war era. So I think this is tied up in ideological convictions of partisanship, but really also in polarization. It’s no longer acceptable to have reasonable disagreements. I do think that the structure of public discourse on social media has conditioned us in such a way as to stick to our guns no matter what, to really not be permitted to make mistakes or reverse our judgment even if that means rejecting the decades of scientific research that have been undertaken. And then also looking for signals that substantiate that existing bias that one has.

Isolation is not a protection strategy

Scott White: We had a question sent in to us about someone who’s homeschooled their kids and therefore they believe that that minimizes exposure to others. Again, you hear this from some people. “I don’t get out much” or “I don’t work in an office” or “I work outside, so therefore I don’t really need to be vaccinated.” How would you respond to someone who said something like that?

Zain Chagla: I have seen people who have tried their best to isolate people that were homebound, but are reliant on certain people to be in their environment for their care that have gotten COVID. So number one, reducing your contacts and staying at home will reduce your risk, but it’s fallible. There are ways that people can get through it. People have to still go to the grocery store, people eventually have to see family, people have to get in public transit, and other ways that people came at exposed. Number two, there is this overlying belief that COVID-19 is somehow going to disappear from the face of this earth. And it’s not, right? This is going to be one of our endemic viruses. It’s not there yet. We’re still seeing epidemic spread, but this is going to be there today, it’s going to be there tomorrow, it’s going to be there the next day. And so, unless you plan on you and your family living a lifestyle where you’re going to be homeschooled and staying at home for the foreseeable decade or two, you’re going to encounter COVID at some point or another. And again, the best thing you can do for your body is have immunity to the virus and have a head start so that when you are encountering this virus, you can deal with it.

Can minds be changed at this stage?

Scott White: Cliff, as someone who’s taking the pulse of the public all the time, do you think that at this stage, almost a year to when the vaccines have been available, is there anything that can be done to convince those who haven’t been vaccinated to actually make that decision now?

Clifton van der Linden: I think there are some difficult decisions that policy makers have to engage with around this. We’ve seen the efficacy of mandatory vaccinations in certain sectors that has led to people who don’t want to be vaccinated, but nevertheless have made the decision to be vaccinated based on the policies that were put in place. That’s not something that should be done lightly. I think there are reasonable concerns about the government imposing mandatory measures, but there are choices to be made about the collective health of the population. And I will say that what we see in the data of public opinion is that the people who are reluctant to get vaccinated are not a homogenous group. There are different clusters within that group who have different motivations, ideas. They’re basing their decisions on different information and intuition and feelings. And they have different interactions with the public health-care system. But in terms of what we can do, I think it goes back to almost the beginning of the conversation and the really insightful things that my colleagues on this panel have spoken about, which is certainly any frame or any conversation that seeks to patronize or belittle the reasons that people have for not getting vaccinated is probably not going to end up being a successful path to convincing them otherwise. And these are not by and large people who haven’t read anything or who haven’t looked up information in the vaccine or who haven’t taken this very seriously. They do take it seriously. They read a lot about it. But there have been decades of concerted efforts to undermine science when it conflicts with certain interests. Look at the science on climate change for example. This is not something that’s new that has eroded confidence in science in general. We have also consistently underfunded STEM in our public education systems. And that lack of funding has led to an inability to discern authentic information from disinformation and misinformation in the broader public. So it’s almost a perfect storm of institutional and political failings that has led us at this point. I don’t fault individuals by and large. I think we have to think about the system that has led us to the place in which we are now.

Scott White, CEO | Editor-in-Chief, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.