Lauren Ralph, University of California, San Francisco

The big idea

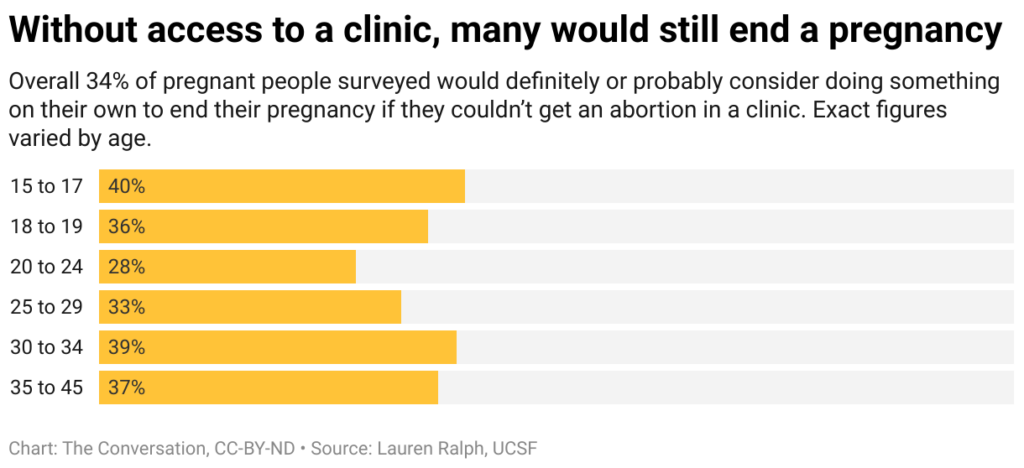

One in three people in need of abortion will consider doing something on their own to end the pregnancy if they are unable to get an abortion at a clinic. These are the findings of a study I recently published after surveying over 700 people seeking abortions in three states across the U.S.: Illinois, California and New Mexico.

The one-in-three figure is even higher among those who have a difficult time affording the cost of their abortion, have no health insurance or are seeking an abortion because of concerns about their own physical or mental health.

These findings offer a clear snapshot of what lies ahead as states move to ban abortion outright or severely restrict access.

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

Why it matters

Research over the past two decades has shown that pregnant people who face obstacles to getting to an abortion clinic or who have a desire for a more natural or private abortion experience will try to end a pregnancy on their own. This might include turning to self-sourced abortion pills, alcohol or drugs, herbs or physical methods.

My own research in 2017 found that 7% of U.S. women of reproductive age will use one of these methods in their lifetime to try to end a pregnancy outside of the formal health care system.

What has changed recently – and dramatically – is access to clinic-based abortion. With the Supreme Court’s decision overturning federal protections on abortion access, as of Aug. 30, 2022, 14 states have already implemented bans on abortion; an additional 12 are projected to do so in the coming months.

These restricted-abortion states are home to just over one-half of U.S. women of reproductive age. Putting these numbers together with data on who seeks abortion in the U.S., researchers estimate that over 100,000 pregnant people per year will soon face insurmountable travel distances to their nearest abortion provider and be unable to get an abortion at a clinic.

If people do as they project in our study, around 33,000 pregnant people per year will consider doing something on their own to end a pregnancy.

What still isn’t known

One yet unanswered question is how many of those in need of abortion and unable to get to a clinic will be able to end a pregnancy on their own with a safe and effective method such as the FDA-approved medications mifepristone and misoprostol, or misoprostol alone – versus how many will turn to other, likely less effective, methods with potentially harmful outcomes.

Researchers now have clear evidence that telehealth and mail-order models enabling access to medication abortion without the need for an in-person visit with a health care provider – models accelerated in part by the COVID-19 pandemic – are safe, effective and satisfactory to patients.

However, these models will remain out of reach for some. This is especially true for those who are further along in their pregnancy, cannot afford the cost, live in one of the 19 states that ban telehealth provision of medication abortion or don’t have a safe place to receive and use the pills.

What is also unknown is how many pregnant people will face legal repercussions for doing something to try to end a pregnancy. Although public support for criminalizing a pregnant person for self-managing an abortion is low, state legislators are actively proposing such policies. Between 2000 and 2020, more than 61 people were investigated or arrested for such attempts.

What’s next

In the coming months, my colleagues and I will document the magnitude of any increase in self-managed abortion by repeating a nationally representative survey that we fielded in 2017 and 2021.

Our research underscores that even when abortion is restricted, people will move forward with abortion on their own. Having access to abortion pills is critical so that when people need to self-manage an abortion, the health, medical and advocacy community is supporting them to do so safely and effectively.

Lauren Ralph, Associate Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of California, San Francisco

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.