From the University of Washington

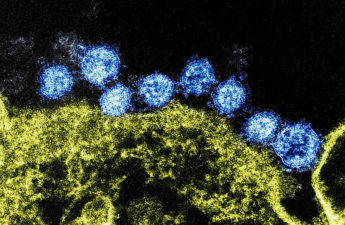

People with genital infection with the “cold sore” herpes virus, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), frequently shed the virus in the first months after infection, raising the risk they might spread the virus to their sexual partners during this time, but the rate of shedding declines rapidly during the first year, researchers from the University of Washington (UW) School of Medicine in Seattle have found.

“The findings suggest that the infection with genital HSV-1 is quite different than genital HSV-2, as it is substantially less severe both in terms of recurrences and shedding. With HSV-2, we continue to we see high rates of shedding many years after first-episode infection,” said Dr. Christine Johnston, associate professor of allergy and infectious disease. Johnston was the lead author on paper, which was published Oct. 22 by JAMA. Read the paper.

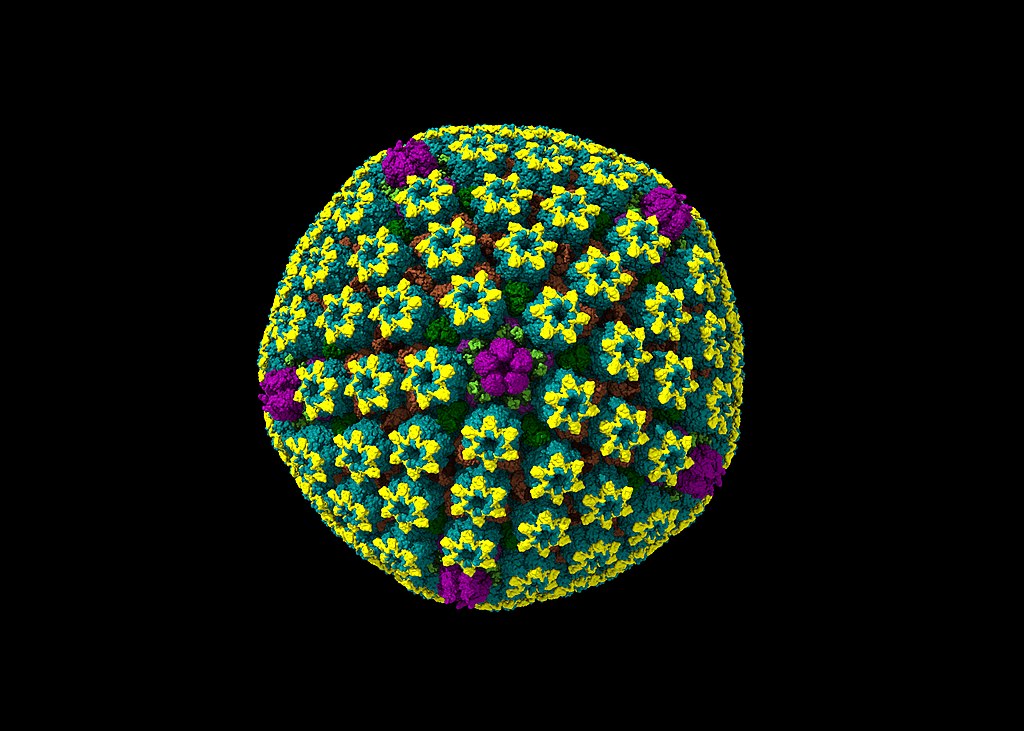

In the past, HSV-1 was primarily associated with the blisters and ulcers on the lips often referred to as cold sores, or fever blisters and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), a closely related virus, was primarily responsible for genital herpes. But that has changed over the past several decades, and today HSV-1 is the leading cause of new genital herpes infections in many parts of the world.

In the last several decades, fewer people have been infected with HSV-1 in childhood, making them susceptible to infection when they become sexually active.

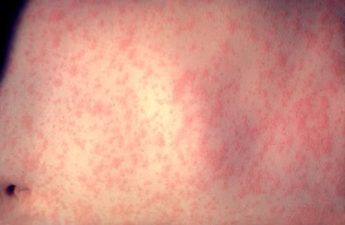

Most genital herpes infections are acquired without symptoms. But when symptoms occur, they can include often-painful genital blisters and sores, fever, chills, fatigue, muscle aches and other flu-like symptoms. Infections can also cause emotional distress, as patients might feel the social stigma associated with infection and worry about transmitting the virus to their sexual partners and, if they are going to give birth, to their newborn.

In the new study, Johnston and colleagues sought to better understand the course of genital infections with HSV-1 and how the immune system responds. Although it is known HSV-1 appears to cause less frequent genital symptoms than HSV-2, this was the first study to comprehensively examine oral and genital HSV-1 shedding using the highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test.

They enrolled 82 men and women who had been diagnosed with their first episode of genital HSV-1 infection. Fifty-four (66%) were women and 28 (34%) were men. Their ages ranged from 16 to 64 years, with a median age of 26. Antibody studies indicated that about half of the participants had been infected with HSV-1 before.

To detect shedding, the participants swabbed their mouths and genitals daily for 30 days, at two and 11 months after their first episode of genital HSV-1. The swabs were tested for the presence of HSV-1. Blood samples were also collected at several points during the study to analyze the participants’ immune response to the infection. The enrollees took an antiviral drug to treat their initial episode but agreed not to take treatments to suppress the virus during the periods when samples were collected.

The number of days participants shed virus varied. Some participants shed no virus at all, but shedding was relatively common at two months, with the participants shedding HSV-1 on 12% of days. At 11 months, however, the rate had fallen to 7% of days. In most instances, participants did not have symptoms even though they were shedding virus.

The participants who shed at least 10% of days at 11 months did another 30 days of swabbing two years after their initial genital infection. In this group, the rate of shedding had fallen even further, to 1.3% of days. Although the sample size was small, the rates are considerably lower than is seen with HSV-2, in which shedding occurs on about 34% of days in the first year and remains at 17% of days at 10 years. In parallel to shedding, recurrences were infrequent, with an average of one recurrence during the first year of infection.

“I think patients can feel some reassurance that with genital HSV-1 infection, you are likely to have less shedding and have a lower risk of transmitting the virus than you would with HSV-2 infection,” said Johnston.

Analysis of sampled viruses and the participant’s immune response to the infection did not explain why shedding rates differed among participants. But shedding was more common among those for whom this was a newly acquired infection.

Patients who lack antibodies for HSV-1 and -2 when they are diagnosed with their first case of genital herpes should be advised to expect more frequent shedding, Johnston said, and they may be candidates for suppressive antiviral therapy during the first year of infection.

And although neonatal herpes is rare, it can be devastating, she added. The finding that shedding is common in the first months after infection underscores the importance of identifying pregnant people at high risk of acquiring HSV-1 so that preventive steps can be taken to avoid infection.

The JAMA paper is accopanied by an editorial, Shedding patterns of genital herpes simplex virus infections, by Richard J. Whitley and Edward W. Hook, Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham. They discuss the potential clinical and research implications of the findings.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (75N93019C00063, R01 AI132392, R21 AI130676, T32 GM 102057-5), the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (P01 AI030731), and a Pennsylvania State University Kern Graduate School Academic Computing Fellowship.

The JAMA article is titled Viral shedding 1 year following first episode of HSV-1 infection.

The authors conflict of interest statement is available in the paper, or by contacting UW Medicine media relations.