China is the only major country which, until now, has continued to enforce a zero-COVID strategy. Other countries, including Australia, New Zealand and Singapore, also sought to eliminate COVID entirely earlier in the pandemic. But all eventually abandoned this approach because of the mounting social and economic costs and the realisation that local elimination of COVID was largely futile and only transient.

China’s strategy, which has relied on measures including mass testing, shutdowns of entire cities and provinces, and quarantining anyone who may have been exposed to the virus, has increasingly become untenable. The harsh and often arbitrary enforcement of zero COVID has fuelled growing resentment among the population, culminating in large public protests.

The restrictions have also shown their limits in the face of omicron. This variant has a shorter incubation period than previous COVID lineages, and largely bypasses protection against infection conferred by the original vaccines.

It’s logical that Chinese authorities are now moving to ease restrictions. However, the transition out of zero COVID has been painful for any country that’s done it. And China faces some unique challenges in making this shift.

Low population immunity

China has successfully suppressed widespread COVID transmission since early 2020. Although figures differ between sources, close to 10 million cases have been reported to the World Health Organization since January 2020. This represents only a tiny fraction of the country’s population, numbering 1.4 billion. So the Chinese population has acquired minimal immunity to COVID through exposure to the virus to date.

Vaccination rates in China are largely in line with those in western countries. But an unusual feature of China’s vaccination rates is that they decrease with age. Older adults are by far the demographic at highest risk of severe COVID, yet only 40% of people over 80 have received three doses.

Vaccine efficacy against transmission has been severely tested, especially since omicron started spreading in late 2021. That said, protection against severe disease and death provided by the mRNA vaccines used in western countries has remained high.

China has used different vaccines; primarily “inactivated” shots made by Sinovac and Sinopharm. Inactivated vaccines are based on pathogens (so SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in this case) but these are killed, or inactivated, before inoculation. Inactivated vaccines are generally safe, but they tend to elicit lower immune responses than newer vaccine technologies, such as mRNA (Pfizer and Moderna) or adenovirus vector-based vaccines (AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson).

The performance of the Chinese vaccines has been mixed. While two doses of the Sinovac shot reduced deaths by 86% in Chile, results from Singapore suggested the inactivated vaccines provided poorer protection against severe disease relative to their mRNA counterparts.

It’s true the globally dominant omicron variant is associated with significantly lower disease severity and death than the delta variant it replaced. But omicron remains a major threat for populations with little prior immunity – particularly among the elderly.

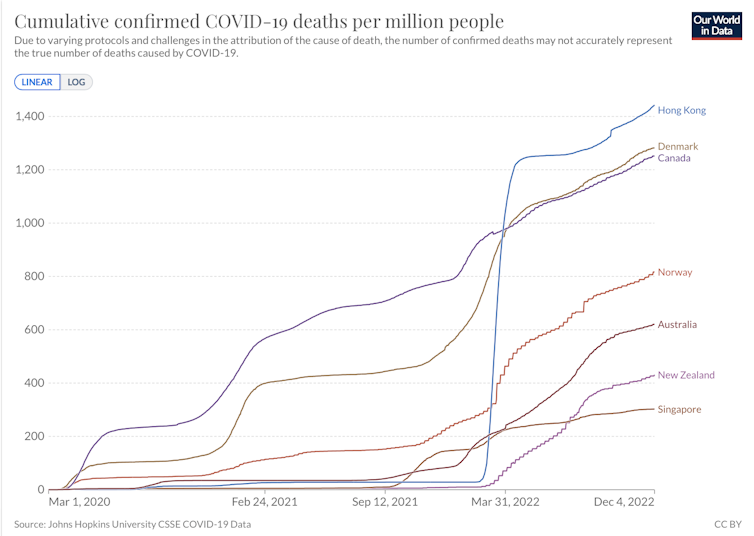

Hong Kong was facing similar problems to mainland China in early 2022 with comparably low virus exposure across the population. Hong Kong had even poorer vaccination rates among older adults than China does now, though a more robust healthcare system. The omicron wave that swept Hong Kong in March 2022 led to more deaths per inhabitant in a matter of days than many countries have seen through the entire pandemic.

COVID infections are now rising quickly in China, numbering above 30,000 new daily cases in recent days. As various restrictions are eased, there’s little question numbers will continue to surge.

Given the low level of immunity in China, a major surge would likely see large numbers of hospitalisations and might lead to a dramatic death toll. If we assume, say, 70% of the Chinese population becomes infected over the coming months, then if 0.1% of those infected die (a conservative estimate of omicron’s mortality rate in a population with hardly any prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2), a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests we’d see around one million deaths.

There’s relatively little China can do at this stage to avert significant death and disease – though any last-ditch vaccination campaign focusing on older adults will likely help.

Chinese healthcare is fairly fragile and the dearth of critical care beds represents a particular vulnerability. The country would be well-served to lift restrictions gradually, to try to “flatten the curve” and avoid the healthcare system becoming overwhelmed. Effective triaging of patients, in particular ensuring that only those most in need of care are admitted to hospital, could help reduce deaths if the epidemic got out of control.

A possible catastrophe

A major wave in China won’t necessarily have a significant impact on the global COVID situation. The SARS-CoV-2 lineages currently spreading in China, such as BF.7, can be found elsewhere around the world. Circulation in a largely immunologically naive population should not exert much additional pressure on the virus to evolve new variants that can escape our immunity.

But China is facing a possible humanitarian catastrophe, and I would argue this is a much greater challenge.

There’s an irony in China having been the first country affected by COVID and also the last to give up on its elimination. Chinese authorities pioneered and championed unprecedented measures to suppress viral spread, providing a blueprint for harsh pandemic suppression strategies globally. China then implemented those measures more ruthlessly and for longer than any other major country.

Yet in the end, zero COVID proved largely futile. China, the last domino, will fall soon due to the unsustainable social and economic costs of zero-COVID policies. The virus will spread in China as it did elsewhere, leaving in its wake its trademark of disease, death and bitter dissension in the population.

Francois Balloux, Chair Professor, Computational Biology, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.