By Sharon Reynolds, National Cancer Institute

September 12, 2023

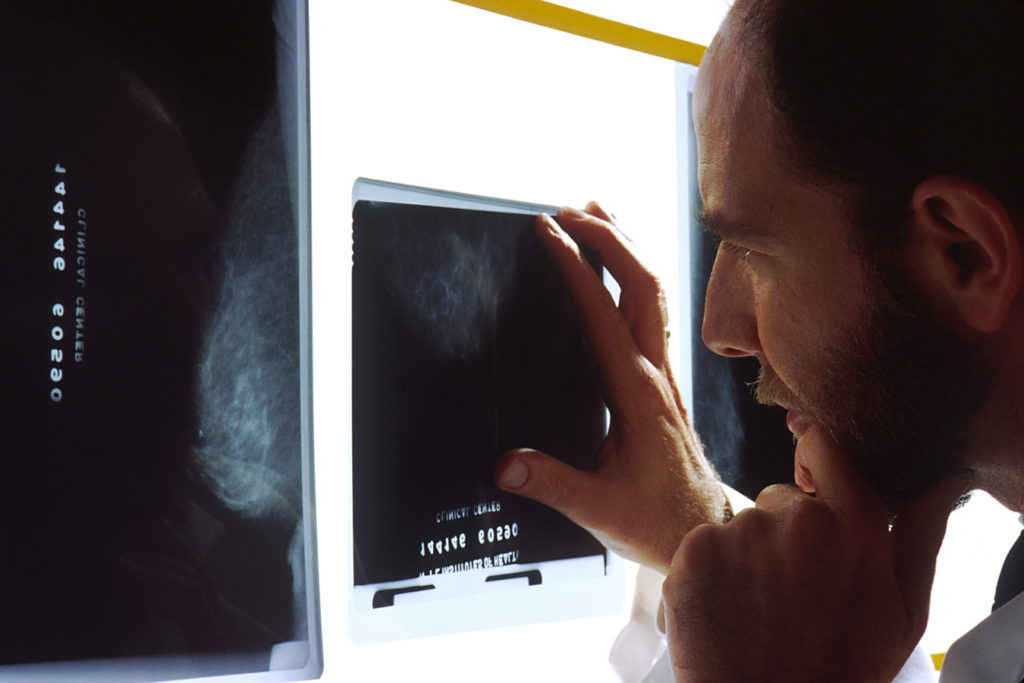

It has become widely accepted that it’s always best to find breast cancer as early as possible, when the cancer is less likely to have spread elsewhere in the body and less aggressive treatment may be needed.

And studies have shown that routine screening mammography does reduce breast cancer deaths in women aged 40 to 75.

But screening also comes with downsides, which include the risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. A new study suggests that the risk of overdiagnosis with routine screening mammography is substantial for women in their 70s and older.

And this overdiagnosis risk escalates with increasing age and other health problems, according to findings published August 8 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The concept of overdiagnosis is a tricky one. It doesn’t refer to false positives—test results that indicate that a suspicious mass is cancer when further tests show that it actually isn’t. Instead, in overdiagnosis, a screening test does find a true cancer. But it’s a cancer that will grow very slowly—or not at all—and would never cause problems during someone’s lifetime.

Treatment for such cancers would, by definition, be unnecessary. But since there is currently no way to tell which breast cancers found on screening mammograms will grow, and how fast, women who have such cancers almost always have surgery, and sometimes additional treatments.

Because older or frail women are most likely to have a shorter remaining life span, the prospect of overdiagnosis has led to sometimes intense debate about whether it’s appropriate to screen these women for breast cancer.

“The suggestion that screening may not be helpful [for some people] is tricky,” said Ilana Richman, M.D., from Yale School of Medicine, who led the new study. “We don’t want our patients to think that we’re giving up on them, when what we’re really after is just the opposite—focusing on care that improves quality of life by avoiding tests that are unlikely to be beneficial.”

“It can often take 10, 20, even 30 years for a slow-growing breast cancer to cause harm,” added Mara Schonberg, M.D., from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, who was not involved with the new study. “So, for older women with other health conditions, with frailty, … diagnosing breast cancer and treating it [may] only cause additional problems.”

Modeling screening mammography in older women

Rigorous clinical trials to evaluate the ability of cancer screening tests to save lives all follow a similar design, Dr. Richman explained. They enroll a large number of participants, who are randomly assigned to either undergo routine screening or not. These participants are then followed for many years, to see if there are fewer deaths from cancer in the screened group over time.

Differences in the number of cancers detected don’t provide information about the effectiveness of screening, because more cancers will always be found if one looks for them. In fact, if a study finds many more cancers in people who are screened but no decrease in cancer deaths, that is more likely to be evidence of overdiagnosis than of any benefit for screening.

Studies conducted over the past few decades have found that women ages 40 to 74 who are regularly screened for breast cancer have a small but meaningfully reduced risk of dying of the disease. But rigorous trials have not included women over the age of 75, Dr. Richman said.

To approximate such a trial, Dr. Richman and her colleagues used data from more than 50,000 women enrolled in Medicare whose records were linked to NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. All had undergone screening mammography in 2002. None had had breast cancer, and all were aged 70 or older by January 1, 2003.

The researchers divided the women into two groups based on whether they’d had another screening mammogram at some point during the next 3 years. This allowed them to mimic the way participants would be split up in a clinical trial, with half assigned to continue screening and the other half to have no further screening.

They then compared how many women were diagnosed with breast cancer (incidence) and how many died from breast cancer over the remainder of their lives.

Increasing age, increasing risk of overdiagnosis

The women were followed through 2017 or until they were diagnosed with breast cancer or died. Overall, women in the study aged 70 to 74 were followed for a median of almost 14 years, those aged 75 to 84 for a median of 10 years, and those aged 85 and older for a median of about 5 and a half years.

More cancers were found in women who continued screening—for example, among women aged 70 to 74 years, cancers were detected in about 6 of 100 women during the follow-up period, whereas they were detected in about 4 of 100 women who weren’t screened.

But the researchers did not see differences between the groups in the number of cancers that were diagnosed at more advanced stages, which are more likely to be lethal, or in deaths from breast cancer. They did see a difference in the number of cancers detected at an earlier stage, but this didn’t translate into a decrease in deaths from breast cancer.

Based on the differences in diagnoses between the two groups, the researchers estimated that, among women aged 70 to 74 diagnosed with breast cancer on screening mammography, around 31% would be overdiagnosed. These overdiagnosis estimates rose to 47% for women aged 75 to 84 and more than 50% for some women who had a life expectancy of less than 5 years (based on their age and other health conditions).

The study’s main takeaway message shouldn’t be the exact overdiagnosis percentages, since these can vary based on the methods used to estimate them, said Natasha Stout, Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“And it’s important to remember that overdiagnosis is only something you can measure looking back, at the population level. You can never say, for any one individual woman, whether overdiagnosis happened,” Dr. Stout added.

“But across studies, the [overdiagnosis] numbers are big enough to be pretty meaningful for women” aged 70 and older overall, she said. “We need to be thinking about overdiagnosis as a potential harm from screening tests in general, and people need to be aware [of it].”

Having hard conversations about mammography

The new study’s results highlight the need for conversations between older women and their health care providers about the potential benefits and harms of continuing screening mammography.

“These are not easy conversations to have,” said Dr. Stout. By nature, they include a discussion of life expectancy and death, she explained, which can be difficult to handle in a sensitive manner.

“But [these conversations] aren’t about giving up on people, in any way. It’s about not doing harm when a test is unlikely to be helpful,” said Dr. Richman.

And the potential harms of overdiagnosis can be substantial.

When cancer, even a very small one, is found on a screening mammogram, “most of these women have surgeries, some will have radiation therapy, a smaller percentage will have chemotherapy,” explained Dr. Richman. “Even after something like a [lumpectomy], older women risk functional decline. It can set them back in terms of how much they’re able to do for themselves.”

But people put different values on different potential health outcomes, she added. And there are gray areas in decisions about screening. Women in their 70s offer an ideal example, she said.

“We have data that suggests that screening is helpful [for these women]. But overdiagnosis probably also exists,” she said. So it’s important for clinicians talking to their older patients to acknowledge that those two things can occur simultaneously, she continued, and that different people may make different choices about continuing or stopping screening.

Can some women have less treatment?

Drs. Schonberg and Stout have been developing an online conversation aid to help doctors and older women have these difficult conversations.

The tool is designed to be used within the limited amount of time allocated for a wellness visit, they explained, but in a way that still takes individual concerns and values into account. These include the fact that some women, because of risk factors like family history or breast density, will have a higher likelihood of developing breast cancer than others.

The conversation aid is currently undergoing testing, “but we hope that having this kind of tool will address some of the barriers to these conversations,” Dr. Schonberg said.

Methods to determine which cancers found on screening may be very slow growing—and can potentially be simply monitored, or treated with hormone therapy alone—are also needed, wrote Otis Brawley, M.D., and Rohan Ramalingam, M.D., of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, in an editorial that accompanied the new study. That includes identifying potential molecular features of these slow-growing cancers, they wrote, similar to what is already done to identify which treatments are best for specific forms of breast cancer.

If such biomarkers can eventually be developed, “we might be able to move precision or personalized medicine to the point that we can distinguish types of cancer that are a threat and need treatment versus those that are indolent but merit observation,” they explained.

In the meantime, new studies are starting to test whether these more conservative approaches to treatment may be safe for some women with small cancers found on screening mammograms.

“There’s a lot of interest in the oncology world in asking: Can we better predict which treatments are necessary and which are not, so that for some women, we can safely do less?” said Dr. Richman.