From UW Medicine

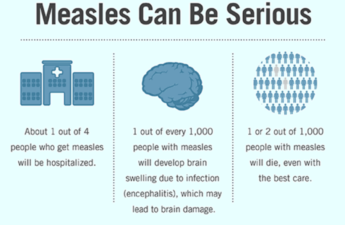

The most common cause of the common cold, the rhinovirus, increases its chances of infecting someone who lacks immunity by simultaneously circulating many versions of itself, according to new research from the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

“With viruses like SARS-CoV-2 or influenza, one variant will dominate for a while and then another takes over, and it, in turn, is replaced by another,” said Dr. Alex Greninger, professor of laboratory medicine and pathology, who led the study. “Rhinovirus, on the other hand, appears to flood the zone with many discrete variants circulating in the community at the same time. It’s a way to overcome your defenses with sheer numbers.”

The findings were published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Although the rhinovirus is the most common cause of upper respiratory infections, relatively little is known about how it evolves and spreads. In their study, the researchers analyzed nasal swabs taken at Seattle-area collection sites during the COVID-19 pandemic.

They looked at samples gathered during two periods:

- spring and summer of 2021, when strict COVID-19 public health measures slowed the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and nearly eliminated other common respiratory infections such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

- fall and winter of 2022, when restrictions were relaxed, and influenza and RSV reemerged.

In 2021, while measures slowed the spread of SARS-CoV-2, surprisingly they did not appear to have much influence on rhinovirus infections, which continued to circulate widely.

“Basically, there were only two viruses spreading during the pandemic restrictions, SARS-CoV-2 and rhinovirus, and we were curious about what was going on: Was one rhinovirus species dominating or was there a new, emergent variant causing these infections?” said Stephanie Goya, a postdoctoral research scientist in the Greninger lab. She was lead author of the paper about the findings.

By comparison, the relaxed restrictions of late 2022 led to a resurgence of SARS-CoV-2, influenza and RSV infections, which became known as the “tripledemic.” During this period, too, rhinovirus was found to be widely prevalent.

To find out which viral variants were circulating in the region, the researchers sequenced more than 1,000 RNA genomes of rhinovirus they detected on samples from the tens of thousands of swabs collected during the two spans.

These sequences provided a kind of genetic fingerprint, called a genotype, that allowed the researchers to determine which rhinovirus types were circulating at a given time, and to create the equivalent of family trees to work out how different genotypes were related to each other and how they evolved.

They found that no single dominant rhinovirus variant was causing infections. Instead, 99 different genotypes were circulating in the region during the study spans.

Sixty-six percent of the people whose swabs tested positive for rhinovirus reported symptoms such as sore throat, runny nose and cough. Swabs from people with symptoms tended to have more virus, but no rhinovirus species or genotype seemed to cause more symptoms than another.

The mix of circulating genotypes varied: Some were more prevalent than others at different times. Of particular interest was the finding that genotypes that predominated in the first collection period were largely replaced by other genotypes in the second collection period.

This may be evidence that immunity in the population generated in 2021 influenced which genotypes could spread the following year, Goya noted.

Analysis of the genotypes’ family trees revealed that many of these genotypes aren’t new. They have circulated for up to 40 years, although each genotype has a strikingly stable protein sequence. Researchers believe that the virus’ success comes from having a variety of genotypes present at the same time rather than from a series of new evolutionary changes occurring in each of them. Because each genotype is recognized as distinct by the immune system, each genotype spreads effectively at different times.

Some changes were found in segments of the viral genome that affect the structure of the protein that latches onto cells in the nose and throat. These proteins are often important targets for antibodies and other mechanisms of immune response. Because the structural changes are few, it might be possible to create a vaccine that generates an effective immune response to large numbers of genotypes and, hopefully, prevent many common colds, Goya said.