Samuel J. White, York St John University and Philippe B. Wilson, York St John University

With the popularity of CleanTok on social media, we’re constantly being reminded about how dirty everything around us is. But while you might feel you should disinfect every surface in your home or send your child off to school with antibacterial gels so their hands stay clean, science actually shows us that being exposed to a bit of dirt can be good for kids’ health.

Evidence suggests that exposure to the microbes in dirt might actually help children develop stronger immune systems – and may even decrease their risk of developing allergies and autoimmune diseases.

Mud is not just a mix of soil and water. It’s a complex ecosystem filled with microorganisms. One gram of soil can harbour up to 10 billion microorganisms – of potentially thousands of different species.

The diverse array of bacteria, fungi and other microbes present in mud and soil play a crucial role in our health and is key to what immunologists call “immune training”. This is the process by which the immune system learns to distinguish between harmful pathogens and benign environmental substances.

During childhood, the immune system is especially adaptable. When exposed to a wide variety of microbes, it learns to strike a balance – responding aggressively to harmful invaders while leaving harmless substances, such as pollen or food particles, alone.

But a lack of such training could leave immune systems worse off.

According to the “hygiene hypothesis”, as societies become more urbanised and sanitised, our immune systems are deprived of the microbial challenges they need to develop properly. This may cause the immune system to become hypersensitive, mistaking innocuous substances – such as pollen or dust – for dangerous invaders. This hypersensitivity can manifest as allergic conditions such as asthma, eczema or hay fever.

Lack of microbial exposure, particularly in early childhood, may also increase the likelihood of developing common colds and other childhood illnesses due to the immune system not being properly trained to handle everyday pathogens.

The lack of such immune training could potentially explain why children growing up in sanitised environments (such as cities with limited exposure to animals or nature) are up to 50% more likely to develop conditions such as asthma and food allergies. Their immune systems, unchallenged by natural microbial exposure, may overreact to harmless triggers.

And, without regular microbial interactions, the immune system may turn on the body itself – potentially contributing to the development of autoimmune conditions such as type 1 diabetes or multiple sclerosis. Research even shows that children raised in environments with high levels of microbial exposure – such as farms or homes with pets – are less likely to develop allergies or autoimmune diseases.

There are many reasons why microbial exposure is so good for children’s developing immune systems. For instance, Bacteroides fragilies, which is commonly found in soil, helps produce a key molecule that’s important to immune function.

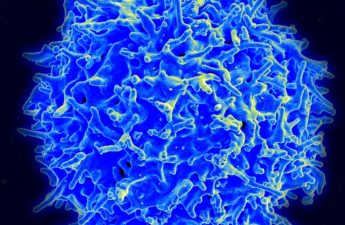

Microbial exposure also helps children develop regulatory T cells – white blood cells that control how the immune system responds to foreign invaders. T cells also prevent autoimmune reactions. This may explains why a lack of microbial exposure may increase a person’s likelihood of developing an autoimmune condition (though this is just one of many contributing factors).

Immune development

Mud play is more than just a messy outdoor activity. It provides essential sensory experiences – such as touching, smelling and manipulating different textures – which stimulate brain development and enhance emotional resilience.

Sensory activities (such as playing in mud) can reduce stress in children, which is another crucial element in maintaining a well-functioning immune system.

Research also shows Mycobacterium vaccae, a type of bacteria commonly found in soil, is shown to reduce inflammation and even improve mood. It does this by influencing the release of serotonin, a key neurotransmitter. In animal studies, exposure to M vaccae has led to reduced symptoms of stress and anxiety. There’s emerging evidence that similar effects could occur in humans.

In addition, playing outdoors is a form of physical activity, which further supports immune health by promoting better circulation and stimulating the production of immune cells.

While some parents may worry about the hygiene risks of playing in mud, there are many things you can do to ensure your kids play outdoors safely:

- Pick clean play areas: Ensure your child plays in areas unlikely to be contaminated by animal waste or harmful chemicals. Home gardens or parks are great options. If you’re unsure how clean an area may be, you can use a soil testing kit to check for harmful substances before play.

- Dress for the mess: Waterproof clothing such as boots and jackets makes clean-up easier while still allowing children to experience the benefits of outdoor play.

- Hand hygiene: Washing hands after playing in the mud helps prevent harmful bacteria from entering the body. This reduces the risk of infections while maintaining healthy exposure to microbes.

- Repeat often: Repeated exposure to beneficial microbes is necessary in order to build a stronger immune system.

Letting children get dirty by playing in mud could offer more than just fun – it may be an essential part of building a strong immune system. In a world that’s increasingly sanitised, embracing nature – dirt and all – might be exactly what our children’s immune systems need to thrive.

Samuel J. White, Associate Professor & Head of Projects, York St John University and Philippe B. Wilson, Associate Pro Vice-Chancellor: Innovation and Knowledge Exchange, York St John University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.