By Michael Ollove, Stateline

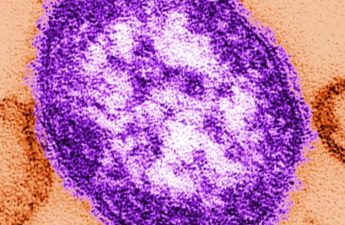

Every state requires children to receive an array of vaccinations before they enroll in school. Typically, those inoculations are for protection against polio, diphtheria, pertussis, measles, rubella, mumps, tetanus, meningitis and chickenpox.

Even though COVID-19 has claimed around 830,000 lives in the United States, including fewer than 700 children, only two states—California and Louisiana—have added COVID-19 vaccines to the list of immunizations mandated for schoolchildren. Both requirements would be enforced next school year, and then only if the vaccines receive full authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The FDA has granted emergency authorization and asserted that the vaccines are safe and effective for children.

The virus is much less deadly for children than adults, and federal regulators continue to review the vaccines for most school-age kids, though final approval is likely coming. There also are bureaucratic complications: Children typically receive the other required vaccines before they enter kindergarten and don’t require additional doses, while at this point, multiple doses of the COVID-19 vaccines are needed to achieve immunity.

But the main reason states are shying away from a vaccine requirement for schoolchildren, public health experts say, is that they are wary of opening yet another front in the wars that have raged over a wide range of COVID-19 rules and restrictions since the pandemic started.

Remote teaching and school masking policies have sparked ferocious conflicts in many communities. And many Republican officeholders and conservative media figures have railed against governments and private businesses for pressuring people to get the shots.

“The polarization describes a lot of why we’re not seeing vaccine requirements,” said Christine Pitts, a policy fellow at the University of Washington’s Center on Reinventing Public Education, which tracks COVID-19 policies in the country’s 100 largest school districts.

Pitts and other policy experts say they don’t see signs that the opposition to COVID-19 vaccine requirements is morphing into generalized pressure on schools to get rid of longstanding requirements for other vaccines.

Nevertheless, the anti-vaccine movement has gained strength during the pandemic. For example, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s anti-vaccine organization, Children’s Health Defense, doubled its donations in 2020, raising $6.8 million, while greatly expanding its reach over the past two years, according to a recent investigation by The Associated Press.

“We’re being very careful not to be intentionally overbearing and allowing school systems to take the lead in their individual jurisdictions,” Dennis Schrader, Maryland’s health secretary, told The Baltimore Sun in September when he was asked about a COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

“We’re being very deferential to them. We’re giving them our guidance and our best advice, but we don’t want to be interventionists in terms of school policy.”

Waiting for Final Approval

Last summer, the U.S. Justice Department issued a memo saying public and private entities, including schools, could make COVID-19 vaccines mandatory under the emergency authorization granted by the FDA.

California and Louisiana have said they won’t enforce their COVID-19 vaccine requirements until next school year, and only if the FDA fully authorizes the vaccines for children. The FDA has fully authorized the Pfizer vaccine for those 16 and over, and granted emergency authorization for children between 5 and 16. The agency hasn’t authorized, even on an emergency basis, either the Moderna or Johnson & Johnson vaccines for those under 18.

Washington, D.C., also has adopted a COVID-19 school vaccination requirement that will take effect in March, but again, only if the vaccine is fully authorized. In New York, Democrats in the legislature also have introduced measures that would institute a COVID-19 vaccine requirement after full FDA approval.

Some large districts, such as the Los Angeles Unified School District, have instituted vaccine mandates that aren’t dependent on the FDA’s full approval. The Los Angeles district planned to shift unvaccinated students to online schooling beginning this month. But last month, faced with 30,000 unvaccinated students, it pushed back the deadline until the fall.

The Oakland, California, school district enacted a similar policy with a deadline of Jan. 1, which it recently extended until the end of this month.

Some other large districts, including New York City, the District of Columbia and some or all districts in California, Hawaii and Maryland, have imposed a vaccine requirement for students who want to participate in extracurricular activities or sports.

Ten states, Washington, D.C., and more than a dozen of the nation’s 100 largest school districts require all teachers and staff to be vaccinated, and hundreds of colleges and universities have mandatory COVID-19 vaccination requirements for students and staff.

Many parents who have not gotten their children vaccinated say the absence of full FDA authorization is a factor, since it suggests that the vaccines have not been fully vetted.

“There are folks that have concerns that this was approved quickly and hasn’t been around very long, so that’s different from the measles vaccine or mumps or tetanus, vaccines that have been around for a long time,” said Hemi Tewarson, executive director of the National Academy for State Health Policy.

According to an analysis by the American Academy of Pediatrics, as of late December, 53% of kids between 12 and 17 had been fully vaccinated, and 23% of those between 5 and 12 had received at least one dose. The Pfizer vaccine for the younger children received emergency authorization late in October; it was approved for older children in May.

Resistance in Red States

While few states are adding COVID-19 vaccinations to their list of required school vaccinations, some are taking steps to block any requirements. According to tracking by the National Academy for State Health Policy, 17 states, most of them dominated by Republicans, have passed legislation banning COVID-19 vaccine requirements for school attendance.

Oklahoma state Sen. Rob Standridge, a Republican, sponsored the measure that became law in his state last year.

Standridge said that while he doesn’t consider himself anti-vaccine, he regards vaccine mandates as discriminatory. “The concern for me is that they were going to target the unvaccinated,” said Standridge, who is a pharmacist.

He cited several reasons for opposing a student COVID-19 vaccine requirement, including reports that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were followed by higher-than-expected incidents of temporary myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart, in males between 16 and 29. (The researchers noted that COVID-19 is much more likely to cause heart problems than the vaccinations.)

He also noted that children have generally had a milder experience with COVID-19 than adults. Consequently, he said he doesn’t feel the government should be forcing parents to vaccinate their children against COVID-19.

“Philosophically and as health professional, these types of medical decisions should be left up to parents for their children,” he said. Still, Standridge said he’s not interested in rolling back other school vaccine requirements.

New Hampshire state Rep. Timothy Lang Sr., also a Republican, sponsored a new law that prevents any public facility, including prisons, government offices, universities and public schools, from requiring a COVID-19 vaccine. However, the law does contain a provision that would allow the state commissioner of Health and Human Services to add the COVID-19 shots to the list of mandatory K-12 inoculations.

Lang, too, said, the decision whether to inoculate should be up to individuals, not government.

“This really comes down to body autonomy,” Lang said, though he added that people who choose not to be vaccinated should be even more scrupulous about observing masking and social distancing measures.

New Hampshire is among the 44 states that allow parents to opt out of school vaccinations for religious reasons or personal beliefs. Lang noted that such requests typically are granted, even in the case of infectious diseases such as measles and mumps. But he fears that would not be the case with a COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

In Louisiana, Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards in November imposed a school COVID-19 vaccine requirement, over the objections of a legislative panel. The policy will go into effect next fall, assuming the FDA has granted full authorization.

“It is worth noting,” Edwards wrote to legislators, “that while many of the diseases on the public health immunization schedule were once both rampant and deadly, they are no longer serious risks for school age children in Louisiana. This is true because almost everyone was vaccinated against these diseases, many as a condition for attending elementary school.”

The history of one of those diseases, polio, suggests that it may be several years before schools across the country mandate a COVID-19 vaccine.

As of late December, COVID-19 had killed 678 children, according the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—only 0.08% of the total U.S. deaths. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, fewer than 1.7% of child COVID-19 cases have resulted in hospitalization and fewer than 0.03% have ended in death.

By contrast, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, before the introduction of the polio vaccine, most of the roughly 35,000 Americans disabled each year by the dreaded disease were children. In the summer, when the virus seemed to peak, many terrified parents were scared to let their kids go to pools, beaches, movie theaters or other community gathering spots.

The polio vaccine was widely hailed as a scientific miracle, and many parents rushed to have their children inoculated as soon as it became available. And yet by 1963, only 20 states plus the District of Columbia had mandated that children get the polio vaccine, or any other vaccine, to attend school.

Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.