By Chloe James and Ian Goodhead, University of Salford Manchester, UK

Moving to a new country can be challenging, not just for us but also for our bacteria. A compelling new study published in Cell suggests migration between certain countries can profoundly affect the bacteria that live in our digestive systems, with important implications for our health.

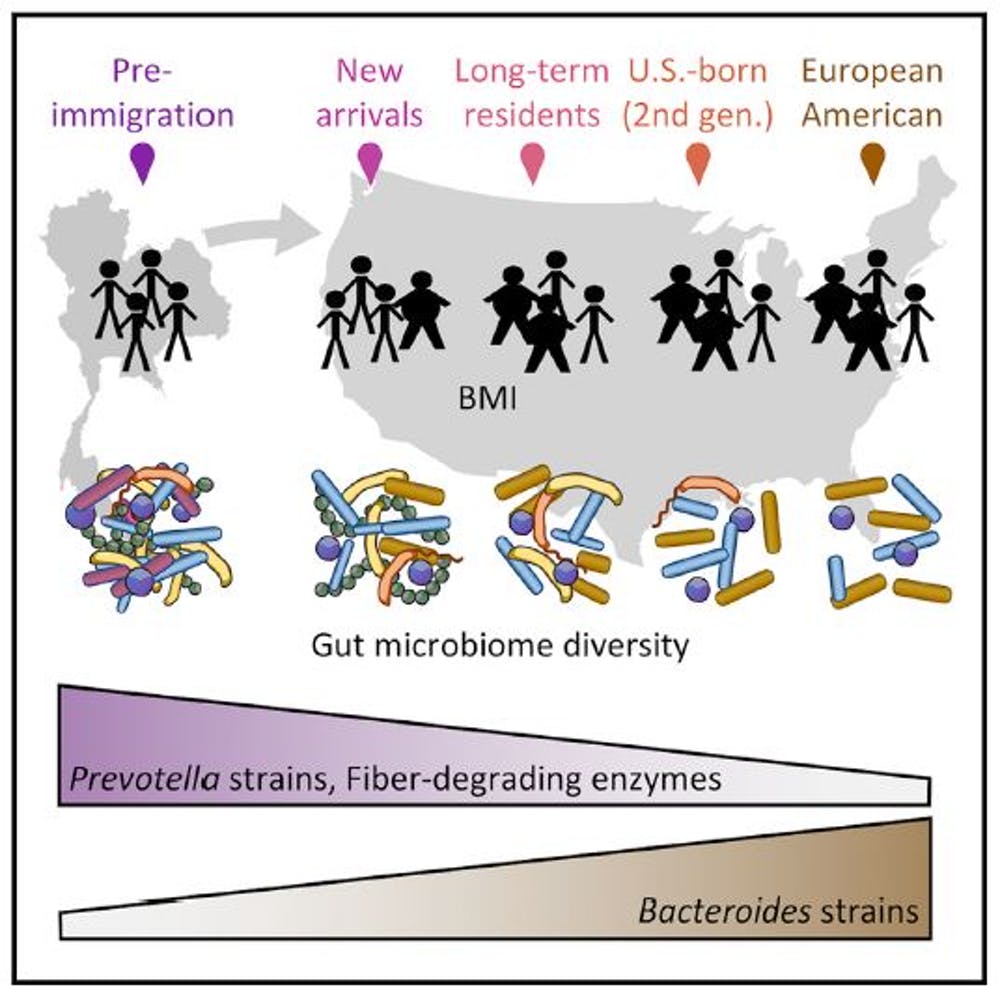

We know immigrants to the US are more susceptible to developing obesity and metabolic diseases such as diabetes than either people from the same countries who don’t migrate or native-born US citizens, but we don’t really understand why. To try to understand this phenomenon from a health perspective, researchers from the University of Minnesota conducted a large, in-depth study of Chinese and Thai immigrants moving to the US. The authors looked at the diet, gut microbes and body mass index of the immigrants before and after they moved. The evidence showed that the longer immigrants spent in the US, the less diverse their bacteria became, and that this was linked to rising obesity.

The human gut is home to hundreds of different species of bacteria known collectively as the “gut microbiome”. As well as breaking down food, this community of microorganisms helps our bodies fight and prevent disease. There is even tantalising evidence that the gut microbiome can influence our mental health.

A more diverse gut microbiome is associated with a healthier digestive system. And things that reduce this diversity, such as antibiotics, stress or changes in diet, can help make us more susceptible to conditions like obesity or irritable bowel disease.

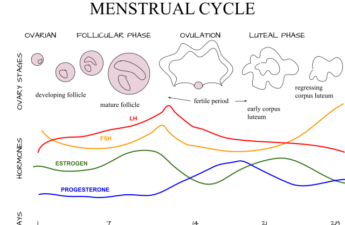

The study compared a total of 514 healthy women, split into those born and living in Thailand, those born in Southeast Asia who later moved to the US, and those born in the US to immigrant parents originally from Southeast Asia. It found that changes to the gut microbiome began as soon as the immigrants arrived in the US and continued to change over decades. The longer they spent living there, the more their microbiomes began to resemble those of native-born Americans of European ethnic origin. The majority of participants, living in the US, also gained weight during the course of the study.

The combination of species that make up our gut microbiomes is strongly influenced by our diets, and so people from different parts of the world tend to have different bacteria. Western guts commonly contain lots of Bacteroides species, which are good at digesting animal fats and proteins. The guts of people with non-Western diets rich in plants tend to be dominated by Prevotella species, which are good at digesting plant fibre. The new study revealed that strains of bacteria from the immigrants’ native countries, particularly Prevotella species, were completely lost, as were relevant enzymes for digesting important plant fibres.

Cause or effect?

Studies that suggest that the microbiome can influence human health or disease are often challenged because it is hard to distinguish between cause and effect. In this case, it’s unclear whether changes in the microbiome are directly contributing to the high incidence of obesity in US immigrants. It may be some time before we fully understand whether a less diverse microbiome leads to obesity, or if obesity leads to a less diverse microbiome.

Most of our knowledge in this area comes from studying laboratory mice. Ground-breaking studies from the lab of US biologist Jeff Gordon first found a link between obesity and the gut microbiome in 2006, when they showed mice gained weight when they were given gut bacteria from obese humans. But, we also know high-fat diets drive obesity regardless of what’s in the gut microbime. So it would be premature to suggest that the microbiome alone is responsible for obesity.

With immigration increasing and eating habits evolving, it is important we better understand how changes in populations, cultures and diets can impact human microbiomes so that we can spot potential health problems. For example, we know that refugees, particularly children, are more prone to developing obesity so we need to develop novel strategies to combat this.

Education is one aspect and another is tackling poverty, which tends to be higher among immigrants than native-born citizens. But if the gut microbiome really is central to health and disease then finding ways to treat it directly by prescribing things like probiotics or even faecal transplants could help. One day we might even have microbial “pills” that could help migrants combat the changes to their gut microbiomes and settle more healthily in their new homes.![]()

Chloe James, Senior Lecturer in Medical Microbiology, University of Salford and Ian Goodhead, Lecturer in Infectious Diseases, University of Salford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.