By Michael Ollove, Stateline

One-year-old Abel Zhang cries earlier this year as he receives the last of three inoculations, including a vaccine for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR), at International Community Health Services in Seattle.

Washington, which recently experienced a serious measles outbreak, has the only state legislature this year that passed tighter vaccination rules, which was signed by the governor May 10.

Despite the worst measles outbreak in decades, few state legislatures this year have reconsidered the exemptions that families use to avoid inoculating their children.

As many legislative sessions wind down, only Washington state, which has had one of the highest numbers of measles cases, has sent a measure to the governor’s desk.

As of last week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported 764 cases of measles in 23 states, the worst outbreak in the United States since 1994.

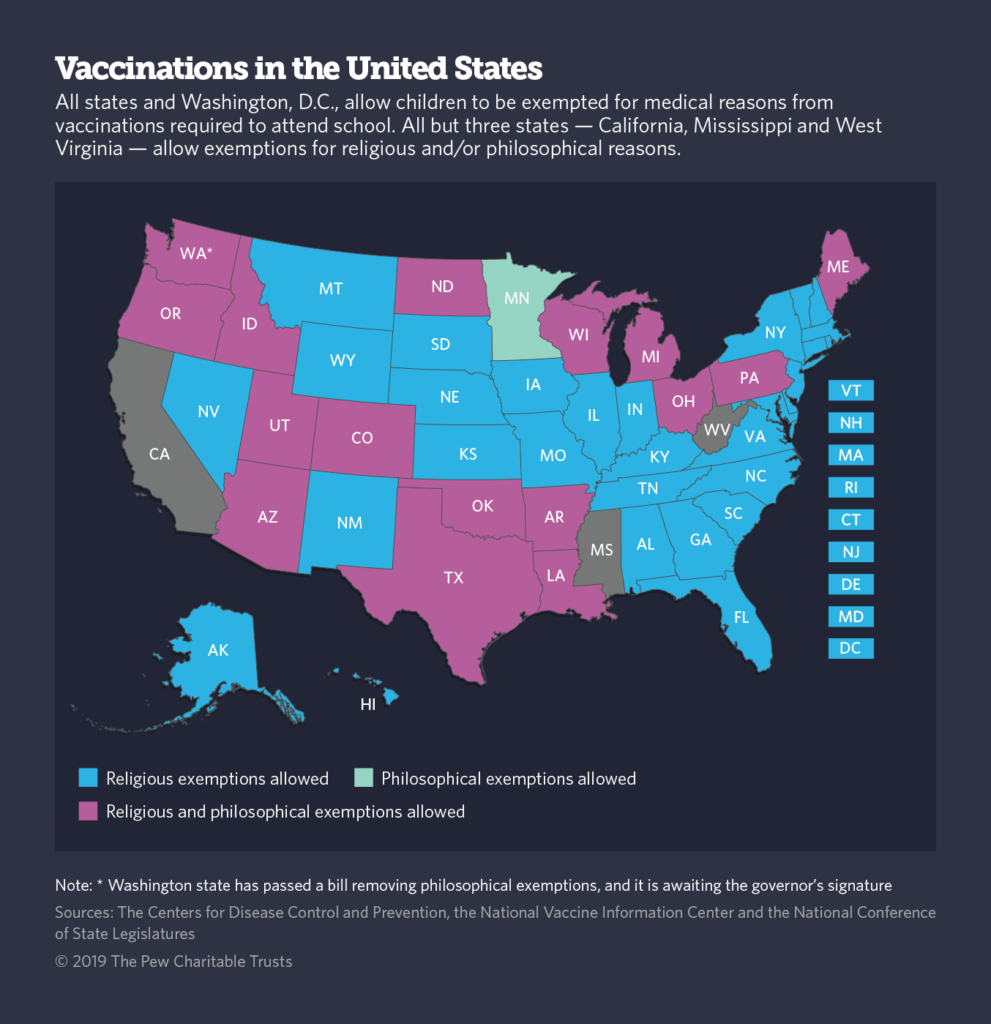

Every state allows schoolchildren to skip inoculations for medical reasons, such as a compromised immune system or an allergy to a vaccine’s components. And all but three states — California, Mississippi and West Virginia — also give passes to families who claim personal or religious objections to vaccinations.

In many states, that number has been growing. For example, the Houston Chronicle reported this week that nonmedical exemptions granted in Texas rose 14% in 2018-2019, continuing a 15-year upward trajectory.

Major medical associations, including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, oppose nonmedical exemptions.

To be sure, the current outbreak began after most state legislative sessions were underway. But proposals to scale back exemptions that did emerge faced vehement opposition from “anti-vaxxer” groups, which scuttled them in several states.

Dr. Sean O’Leary, a Colorado pediatrician who serves on the infectious diseases committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics, blamed such groups for the failure of a bill in his state.

“The anti-vax groups are loud and pretty organized and have worked for years,” he said.

The distinction between exemptions for religious versus personal beliefs can be blurry. Few, if any, organized religious groups oppose vaccinations, and personal belief exemptions are far more common. Immunization experts say legislators often feel more squeamish about being accused of interfering with people’s religious beliefs.

Earlier this week, the Oregon House passed a bill eliminating religious and personal beliefs exemptions. Democratic Gov. Kate Brown indicated her support last month.

In Maine, the two chambers disagree about whether to eliminate all nonmedical exemptions or just the one based on personal beliefs, as opposed to religious objections.

In other states, including Arizona, Hawaii, Iowa and New York, bills have stalled in committee or have otherwise failed to advance.

The Washington bill would eliminate the personal beliefs exemption for the MMR vaccine, while preserving the religious exemption. The MMR vaccine provides protection from measles, mumps and rubella and is given to children in two doses, usually between the ages of 9 and 15 months and again between 4 and 6 years.

Despite medical evidence to the contrary, many anti-vax advocates repeat the myth that vaccines are related to autism.

The Washington state bill did not attract much GOP support, but Republican state Rep. Paul Harris of Clark County, the epicenter of the outbreak, was its author and champion. Clark County had reported 71 measles cases, all among schoolchildren, as of late April, according to the Washington State Department of Health.

State Rep. Monica Stonier, a Democrat who cosponsored the bill, said she would have preferred to eliminate all nonmedical exemptions for all vaccines required for school entrance. She reluctantly accepted the more limited bill, she said, in part because of the current crisis.

“The MMR vaccine is incredibly effective,” Stonier said. “The argument for people who opt out might have been stronger if it wasn’t as effective as it is.”

She also noted that families in Washington who opt out use the personal beliefs exemption more often than the religious one.

In response to an inquiry from Stateline, the state Department of Health reported that in 46 of the cases in Clark County, the child “may” have received an exemption.

The state was able to verify the existence of 22 exemptions. Seventeen of those were based on personal beliefs and four were for religious reasons.

Overall, studies have shown an increase in the number of nonmedical exemptions across the country. The spike has coincided with the rise of an anti-vaccination movement fueled largely by the erroneous claim that the MMR vaccine causes autism. That view gained credence based on a 1998 study in the Lancet, which the British medical journal retracted in 2010.

A 2014 article in the American Journal of Public Health that reviewed 42 studies on the subject found a 19% increase in the rates of nonmedical exemptions granted by the states from 2009 to 2013.

Studies also have shown correlations between the granting of exemptions and vaccination rates and disease outbreaks.

The biggest measles outbreak this year — 690 cases — has occurred in New York state, chiefly among unvaccinated or under-vaccinated ultra-Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn, Queens and Rockland County.

Judaism does not prohibit vaccination, but New York City officials say anti-vaccine activists have targeted the community with misinformation about the debunked link between the MMR vaccination and autism.

Outbreak at Disneyland

James Colgrove, a professor of public health at Columbia University and an expert in immunization policy, said most states began requiring vaccinations for school attendance in the 1960s and ’70s. As those laws spread, so did nonmedical exemptions.

The 2014 measles outbreak at Disneyland in California, which ultimately infected at least 145 people, sparked a debate over such exemptions.

Public health officials blamed the outbreak on the state’s relatively poor vaccination rates, prompting the California State Assembly to eliminate exemptions for both religious and personal beliefs in 2015. Vermont scrapped its personal beliefs exemption the same year.

After California got rid of the nonmedical exemptions, medical exemptions nearly tripled over the next three years.

Colgrove said the California case highlighted the complexity of the issue.

“States differ not just whether they have exemptions, but they differ procedurally too,” he said. In California, parents just needed to sign a form to get an exemption.

Other states, he said, have higher hurdles, requiring notarized forms, affidavits from clergy, meetings with health counselors on the risks of failure to inoculate, or annual reapplication rules. Some require parents to submit statements explaining their moral or philosophical objections.

Mississippi, one of the three states without any nonmedical exemptions, is usually a laggard on health measures. But in the 2017-2018 school year, it had the highest MMR immunization rate for kindergarten-age children in the country.

“We are very proud to have one of the nation’s strictest immunization laws for school-age children,” said Liz Sharlot, a spokeswoman for the state’s health department.

Stateline is an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy. Since its founding in 1998, Stateline has maintained a commitment to the highest standards of non-partisanship, objectivity, and integrity. Its team of veteran journalists combines original reporting with a roundup of the latest news from sources around the country. Stateline focuses on four topics that are key to state policy: fiscal and economic issues, health care, demographics, and the business of government.