Jennifer Reich, University of Colorado Denver

Whenever I talk about my research on how parents come to decide to reject vaccines for their children, my explanations are met with a range of reactions, but I almost always hear the same questions.

What is wrong with those parents? Are they anti-science? Are they anti-expert? Are they simply ignorant or selfish? Are they crazy?

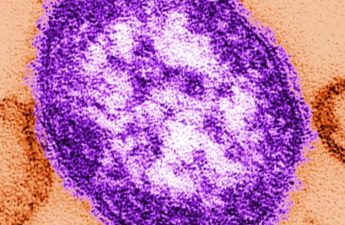

The year is not half over, and the number of measles cases has now exceeded highs not seen since the U.S. was declared measles-free in 2000.

Given the indisputably large role unvaccinated individuals are playing in it, parents who reject vaccines are increasingly vilified.

Some people call to have these parents arrested or punished. Many are asking states to tighten laws that make exemptions to school enrollment without vaccines too easy.

Others dismiss these “Whole Foods moms” as harming others and call for them to be socially ostracized.

As a sociologist, I have spent most of a decade talking to parents, pediatricians, policymakers, lawyers and scientists to understand competing views of vaccines.

In my research, I find that parents who reject vaccines – by which I mean mostly mothers – work hard to make what they see as an informed decision to do what they think is best for their children. They also want to make a decision that best aligns with their belief system.

Experts, at least of their own kids

Many “anti-vax” parents see themselves as experts on their own children, as best able to decide what their children need and whether their child needs a particular vaccine, and better qualified than health experts or public health agencies to decide what is best for their family.

These decisions are inarguably not in the best interests of the community and indisputably increase risk to others who may be the most vulnerable to the worst outcomes of infection.

And although no one can predict how someone will respond to measles infection, children under age five and adults over 20 are most likely to suffer the most serious complications.

The parents who choose to reject vaccines introduce risk to many, including their own children and others. This makes it easy for many people to see them with contempt.

Yet, their decisions also provide an opportunity for all of us to consider how we all may make choices that align with our own goals, but risk the health, and lives, of those in our communities.

Exhibit A: Flu shots

“I totally believe in vaccines. I just don’t get flu shots.”

I hear statements like this all the time from people who consider themselves committed to vaccines and public health. Their statement is not surprising since fewer than 45% of Americans, and fewer than 37% of adults 18-64 without a high-risk health condition, get a flu shot despite recommendations that almost everyone over six months of age should.

Influenza causes more deaths than any other vaccine-preventable disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that in the 2018-2019 season, between 36,400 and 61,200 people died from influenza, of which 109 were children.

The same people who question the motives of parents who reject vaccines often confidently tell me why they didn’t get a flu shot this year, even as they understand that flu can kill. They insist they don’t need it. They contend they are healthy. They have good nutrition. They can handle infection should they become sick. They won’t be one of the 500,000-600,000 people hospitalized this year for influenza-related illness. Some say that the vaccine doesn’t always work anyway, so why bother.

These reasons for rejecting a flu vaccine are the exact same reasons parents offer for why they reject vaccines for their children. After all, they insist, their children won’t be the ones devastated by infection. They are healthy. They eat well. They don’t need those vaccines, either.

Exhibit B: Antibiotics

Beyond vaccines, it turns out many of us are actively contributing to a different kind of public health nightmare: antibiotic resistance. The CDC estimates that each year at least 2 million people are infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and at least 23,000 people die as a result.

One of the major causes is unnecessary antibiotic use. One study suggests that at least 30% and as many as 50% of antibiotics are prescribed unnecessarily.

So why do so many of us jeopardize community health and place others at risk by taking medications that probably won’t help us anyway? Often, those affected by a cold, sore throat, ear infection, cough or bronchitis feel frustrated that their symptoms are interfering with daily life and making them miserable. Surely, there must be some chance an antibiotic will help, the thinking seems to go, so why not try?

As it turns out, people do. Studies show that people frequently store unused antibiotics, borrow them from family and friends, use antibiotics intended for animals and decide without medical advice whether to take them.

From my perspective, this do-it-yourself approach to disease management is not dissimilar to the efforts parents with whom I spoke describe going through to manage risk without vaccines.

Yet, the dangers to others are clear. Research shows that every day of unnecessary antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance, which is increasingly devastating the ability to treat actual bacterial infections.

Room for improvement

There are many ways to support community health and ways we could all do better. For example, monitoring of air quality outside of schools shows elevated levels of benzene, formaldehyde, acetaldehyde and toxins during the hour coinciding with parents picking up their children.

All parents who aim to support children in their community, including those who condemn vaccine hesitance, could protect children’s lungs and reduce children’s risk of developing asthma, respiratory problems and other adverse health effects in one simple way: Turn off your engine in front of schools. Limiting a vehicle’s idling time can dramatically reduce these pollutants and children’s exposure to them. This is an easy way to protect kids, yet some parents insist they need their climate-controlled car or personal convenience, despite the harms it creates.

As the measles continues to spread, we will need to have hard conversations about what we should expect of ourselves and each other.

But as we do, we should take a hard look at how each of us may be undermining community health in myriad ways beyond vaccination. Before embracing calls to publicly sanction or socially shun those who reject vaccines, we could all work to create a stronger culture of public health in which we strive to do better for the most vulnerable among us, even at personal inconvenience.

Jennifer Reich, Professor of Sociology, University of Colorado Denver

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.