By Michael Ollove, Stateline

A young man who had just turned 18 showed up at the Virginia office of Drs. Sterling and Karen Ransone earlier this month and asked for the vaccines for meningitis and human papillomavirus.

It was his first opportunity to be vaccinated. As a minor, he needed permission from his parents, and they wouldn’t grant it because they didn’t think the vaccines were medically necessary. Now, as a legal adult, he could get the shots on his own.

This year there have been at least 1,044 measles cases in 28 states — the largest outbreak since 1992. Public health officials blame parents who have refused to have their kids vaccinated. One way to boost immunization rates is to narrow school vaccination exemptions, which four states have done this year. Another is to take the decision out of parents’ hands and let their kids choose for themselves.

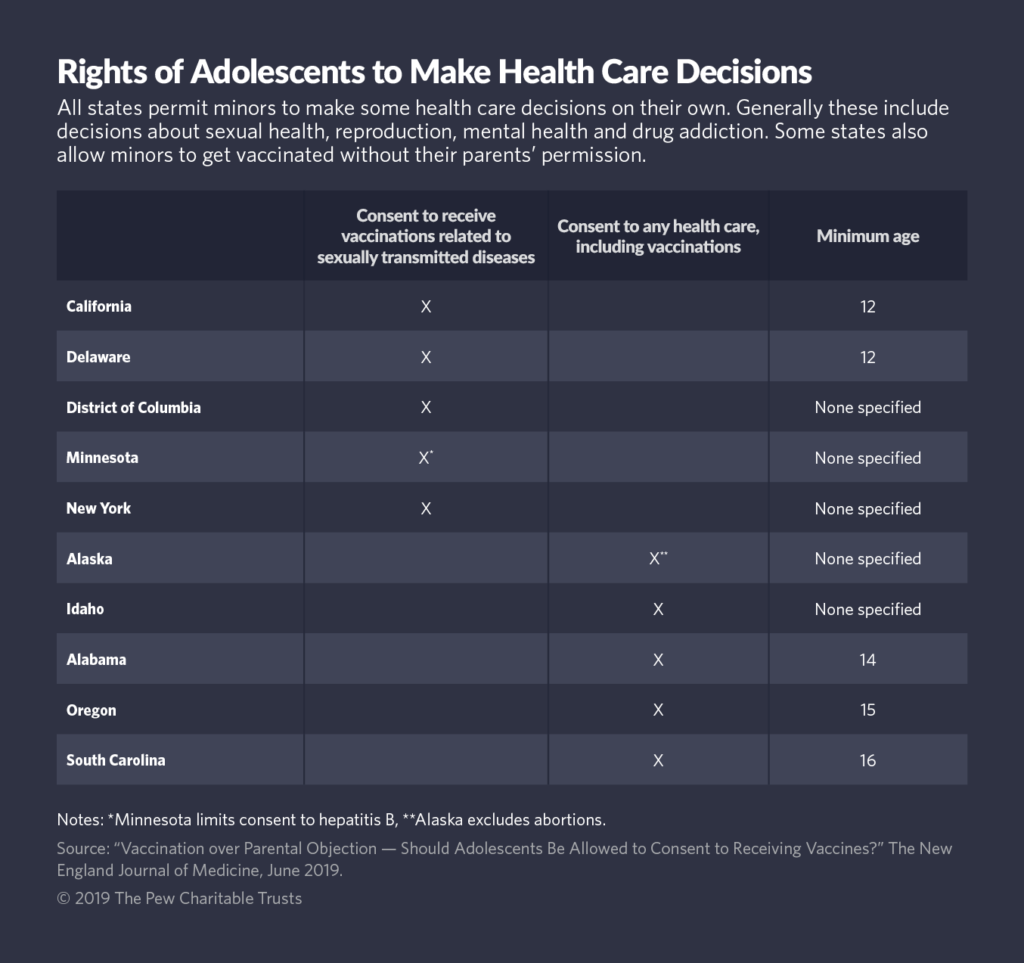

A handful of states already have given teens some vaccination rights. California, Delaware, Minnesota, New York and Washington, D.C., enacted laws years before the current measles outbreak giving minors the right to choose to get vaccinated against sexually transmitted diseases, such as human papillomavirus and hepatitis B.

Alabama, Alaska, Idaho, Oregon and South Carolina have gone further by giving minors the right to make all health care decisions. Some of their laws date to the 1970s, said Ross Silverman, a professor of health policy management at Indiana University Medical School.

The New Jersey General Assembly is debating a bill that would allow 14-year-olds to get vaccinated without their parents’ permission. City leaders in D.C. are considering a measure that would allow adolescents to be vaccinated without permission, as long as a doctor determines they are mature enough to make the decision. A similar bill died in the New York legislature, although its sponsor said she is considering bringing it up again next year.

More states may follow suit if this year’s outbreak is repeated and vaccination rates continue to decline.

“From a public health standpoint, I think all the states are going to have to look at [adolescent] consent for vaccination,” said Sterling Ransone, who practices family medicine alongside his pediatrician wife in a rural area near the Chesapeake Bay.

But David DeLugas, executive director of the National Association of Parents, which promotes the idea that parents should be able to raise their children as they see fit, said empowering children to make health care decisions over the parents’ objections may “introduce discord” into families.

“If we’re going to empower a child of 12 or 14 or 16 to decide something this significant, why wouldn’t they say, ‘If I can make that decision then why can’t I also make any other decision that affects my life?’” he said.

DeLugas is not a vaccine skeptic, and he doesn’t object to some state vaccination requirements, but he doesn’t think states should disrupt the parent-child relationship by taking power from one and bestowing it on the other.

Stateswith minor-consent laws either set a minimum age, which varies from 12-16, or leave it up to a physician to determine if the child has the intellectual capacity to understand the risks and benefits relayed by the doctor. Either way, kids whose parents object to vaccinations can’t get them when they are babies or toddlers, which is when some vaccines, such as the one for measles, are most effective.

Democratic Assemblywoman Patricia Fahy, sponsor of the failed bill in New York, said that while she is leery of doing anything to diminish the authority of parents, the ongoing measles outbreak — nearly 20 years after the United States declared itself measles-free — convinced her that she had to act.

“I respect parental rights and am sensitive to this issue,” she said, “but you have to make public health your first and foremost priority.”

She said the bruising fight in the New York legislature this spring to eliminate religious exemptions left lawmakers with little appetite to take on her measure this year. New York has the highest number of measles cases in the current outbreak. The measure had the support of the New York chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Tetanus in a 6-Year-Old

Parents have broad discretion when it comes to the health care of their children — but there are limits.

“Obviously, in most circumstances parents are the right ones to make decisions that are in the best interests of children,” said Kathleen Bachynski, a postdoctoral fellow in the division of ethics at New York University’s School of Medicine, “but it isn’t an absolute right. Where the child is at risk, the state steps in to limit absolute parent decision-making.”

But states don’t always have the authority to intervene. In 2017, a 6-year-old boy in Oregon whose parents didn’t believe in vaccinations nearly died from tetanus, an almost unheard of disease in the United States thanks to immunizations, after he cut his forehead while playing on a farm.

He spent 57 days in agony in a hospital room and racked up medical bills exceeding $800,000.

He recovered, but his parents still refused to have him immunized for tetanus or anything else, the New York Times reported. There appears to be nothing authorities can do, because Oregon’s law applies only to teenagers 15 and up.

Ohio teen Ethan Lindenberger shined a spotlight on the issue in March when he testified before a U.S. Senate committee. Lindenberger was vaccinated when he turned 18 last year, but he would have done it sooner if his “anti-vaxxer” mother hadn’t forbidden it.

“I went my entire life without vaccinations against diseases such as measles, chicken pox or even polio,” he told the Senate committee.

He didn’t blame his mother but rather the misinformation she encountered online.

“The information leading people to fear for their children, for themselves and for their families is causing outbreaks of preventable diseases,” he concluded.

Private Discussions

Sterling Ransone, the Virginia doctor, said that after his young patients reach a certain age, he excuses parents from the examination room to give the child a chance to talk to him privately. He encourages minors to involve their parents in health care decisions, but there are exceptions.

“We feel strongly that folks in the adolescent range, from 12 to 15, should be able to speak to physicians about concerns of theirs,” he said.

Frequently, those conversations pertain to sexual activity, mental illness and substance abuse, and they are strictly confidential. Kids may not seek the care they need — for STDs, for example — if they know their parents will find out about it.

After a child reaches around 12 years old, the doctor said he doesn’t even permit parents to have access to the electronic health records of their child without the child’s permission. But because minors are on their parents’ health plans, it’s often impossible for their children to keep sensitive information from their parents.

To some degree, all states recognize that older children should have some autonomy in making health care decisions.

Silverman, who co-authored an article in this month’s New England Journal of Medicine on adolescent rights in health care, said all states permit minors to make some health care decisions, especially in “sensitive or stigmatized” areas such as sexual health and drug addiction.

Kids also can consent to emergency care when their parents aren’t present.

The measure under consideration in D.C. would allow minors to consent to all vaccinations the city requires to attend school.

Mary Cheh, the Democratic author of the measure, said she wanted to act before a measles outbreak came to the capital. She said she was mindful of not only unvaccinated children contracting the disease, but the danger posed to Washington residents by exposure to tourists who haven’t been immunized.

“We have the additional problem of all these millions of people who come to the District of Columbia and interact with our people,” she said. “We want to get ahead of the situation.”