Pierre Chandon, INSEAD and Romain Cadario, Boston University

Here are the seven most effective “nudges” that restaurants and grocery stores can use to help tackle the obesity crisis while remaining in business and preserving our right as consumers to splurge if we want to.

A nudge gently pushes us towards making better choices without resorting to economic incentives or restricting our freedom of choice. Reorganising a menu or a grocery shelf is a nudge. Taxing sodas or banning energy drinks is not.

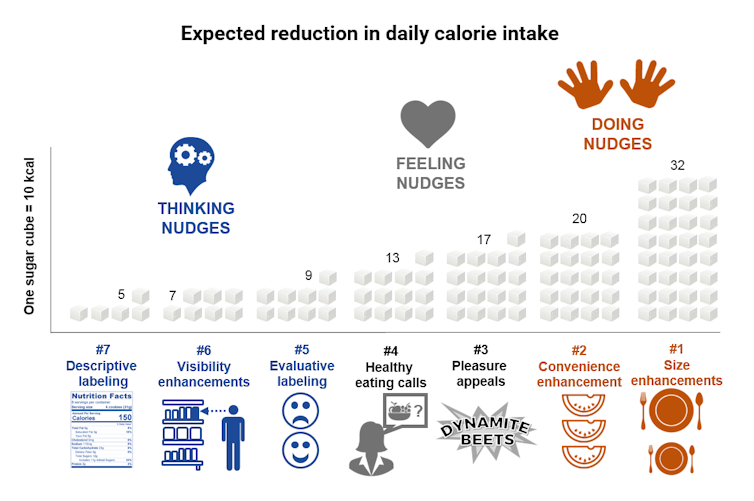

In our study of 96 field experiments, published in Marketing Science, we classified nudges into seven types and measured their effectiveness, after controlling for the characteristics of the respondents, setting and study. We then converted the expected daily decrease in energy intake into sugar cube equivalents. For example, if a nudge can reduce consumption by 100 calories a day, it’s the equivalent of ten sugar cubes.

Here are the healthy eating nudges that work best, in reverse order.

7. Descriptive labelling

The facts alone don’t seem to move the dial very much in terms of making healthy choices. This is nutritional information with no colour-coding or symbols to help people interpret the numbers, and we don’t see any real change with this nudge. Expected calorie reduction = five sugar cubes.

6. Visibility enhancements

Another nudge that speaks to our brains is one that puts the healthiest product in the most visible place – at eye level on a shelf or on the best place in the middle of a menu. Still, it didn’t have a significant impact on making better choices. Expected calorie reduction = seven sugar cubes.

5. Evaluative labelling

When we know how healthy something is in relation to something else, in the form of a smiley face or traffic light food labelling, the information has some impact on our choices. We understand that a red light means “stop”, even in the grocery store. Expected calorie reduction = nine sugar cubes.

4. Healthy eating calls

This is when the cashier asks us if we want a salad with that burger or when there are signs up to encourage us to “make a fresh choice”. In experiments, people start to respond to this type of nudge – something that does more than just inform. Expected calorie reduction = nearly 13 sugar cubes.

3. Pleasure appeals

This nudge emphasises the taste of food. Instead of telling us that carrots are rich in antioxidants, the packaging describes them as “twisted citrus-glazed carrots” to draw attention to how it might taste or feel. Expected calorie reduction = 17 sugar cubes.

2. Convenience enhancements

These nudges make selecting or consuming healthier foods the easy option, such as arranging indulgent foods at the end of the cafeteria line when our tray is already full of healthier foods. Another convenience is pre-cut fruit or vegetables. After all, it’s much easier to eat peeled and chopped pineapple than a whole one. Expected calorie reduction = nearly 20 sugar cubes.

1. Size enhancements

The most effective nudges directly change how much food is put on plates or make the plate or glass smaller to reduce how much we eat or drink. Expected calorie reduction = 32 sugar cubes.

Thinking, feeling, doing

What are the characteristics of the most effective nudges? To answer this question, it is useful to look at what these nudges are trying to influence: our brain, our heart or our hands.

The first three nudges (7, 6, and 5) are trying to inform us about the healthiness of the food options, either by displaying nutrition information or traffic light symbols or by placing the healthiest food right where we will see them. Clearly, they are not ideal. Nudges that inform only have a small impact on our food decisions, reducing our intake by the equivalent of five to nine sugar cubes per day.

The second two nudges (4 and 3) are not just informing us about health, they are trying to make us feel like eating better through an interaction with another person or emotional appeals to our senses. These are more useful, reducing our intake by the equivalent of 13 to 17 sugar cubes.

The last two nudges (2 and 1) try to influence what we do directly, without changing what we know or what we want. They are by far the most effective as they can save us up to 32 sugar cubes worth of calories.

The most effective interventions are not the ones that we think about. Most policy debates are about how to best inform people, for example, with nutrition labels. At least when it comes to eating, feelings beat information and behaviours beat feelings. If shops and restaurants want to help us eat better, they should focus on our hands.

Pierre Chandon, The L’Oréal Chaired Professor of Marketing—Innovation and Creativity and Director of INSEAD-Sorbonne Université Behavioural Lab, INSEAD and Romain Cadario, Assistant Professor at IESEG School of Management & Visiting Assistant Professor, Boston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.