Karen Dwyer, Deakin University and Jaquelyne Hughes, Menzies School of Health Research

Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common genetic kidney disorder, and the fourth most common cause of kidney failure in Australian adults. It affects about one in 1,000 Australians.

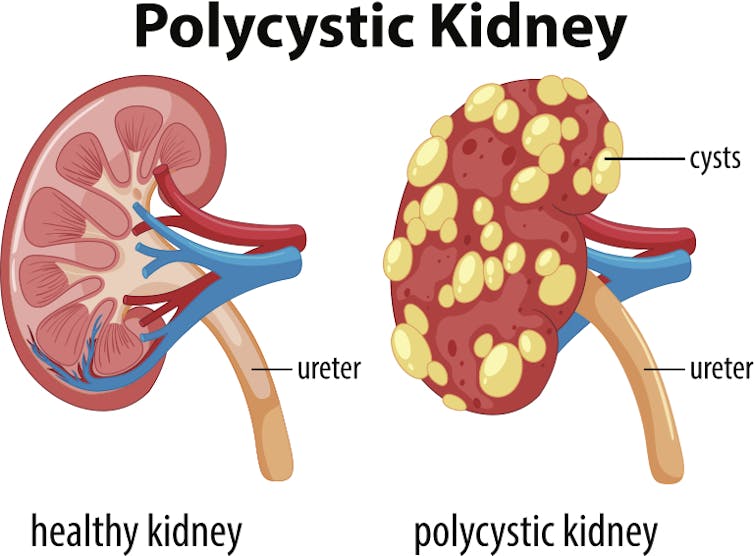

In people with ADPKD, a mutation in one or two genes leads to the development and progressive growth of cysts in the kidneys, causing a decline in kidney function.

Labor senator Malarndirri McCarthy, a Yanyuwa woman, recently spoke publicly about having ADPKD after she became unwell with a kidney infection and had to leave the Senate.

But a newly available treatment for ADPKD shows promise for people with the disease.

Read more: Explainer: what is chronic kidney disease and why are one in three at risk of this silent killer?

What is ADPKD?

If one parent has ADPKD, the children have a 50% chance of inheriting the gene (though up to 10% of patients don’t have a family history).

Where it is inherited, the age of diagnosis and rate of progression to kidney failure in the parent gives some indication of how the disease will develop in affected children.

The cysts are like balloons filled with water, which start small in childhood and increase in size over time.

Typically, the cysts don’t start to cause problems until later in life. The average age at diagnosis is 27 years.

As the cysts grow, normal working tissue in the kidney is replaced with enlarging cysts. So with time, the kidneys don’t work as well.

For about half of people with ADPKD, their condition will eventually progress to kidney failure, which may be treated with dialysis or a transplant.

While the loss of kidney function is paramount, the cysts may cause other symptoms and complications too.

Symptoms can include high blood pressure and chronic pain or heaviness in the back, sides and abdomen. The growth of cysts means the kidneys can grow to as large as 5-6kg in size.

Blood in the urine, urinary tract infections, kidney stones and infections in the cysts are not uncommon in people with ADKPD, and can all impact quality of life.

Other organs may also be affected. People with ADPKD can develop cysts in the liver, pancreas and bowel, and about 10% will experience balloon dilations of the blood vessels in the brain, called aneurysms.

Treatment

Until recently, treatment of ADPKD was directed towards early detection, control of blood pressure, lifestyle measures such as quitting smoking, weight control and diet, antibiotics for infections, analgesics for pain and the management of progressive kidney dysfunction via dialysis and transplantation. None of these therapies however directly slowed the growth of cysts.

But on January 1, 2019, tolvaptan was listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Australia now joins the United States, the European Union, and several other countries where this drug was already available.

Read more: Kidney disease in Aboriginal Australians perpetuates poverty

Tolvaptan, which is taken in tablet form, slows the growth of cysts by blocking a hormone called vasopressin. Vasopressin is critical in triggering the formation of cysts. In this way, tolvaptan prolongs the time to kidney failure.

In one study, three years of treatment with tolvaptan reduced the rate of cyst growth by around 50% in comparison to a placebo treatment. The authors suggested tolvaptan may delay dialysis or the need for a transplant for six to nine years for patients with ADPKD, particularly if started early.

People who took tolvaptan in this study also had lower incidence of ADPKD-related complications including urinary tract infections and kidney pain.

Kidney disease and Indigenous Australians

ADPKD is not actually more common in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, as other causes of chronic kidney disease are. This may be because ADPKD is inherited.

The majority of chronic kidney disease develops as a complication of diabetes, which affects Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations more commonly and typically at a younger age than the overall Australian population.

Kidney disease, whatever the cause, remains a significant issue for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. People in remote Indigenous communities in particular face challenges around accessing treatments in large urban centres, and have poorer access to organ transplants.

Read more: Why simple school sores often lead to heart and kidney disease in Indigenous children

There are several nationally targeted activities and proposals aimed at reducing the burden of chronic kidney disease in Indigenous Australians.

The Renal Health RoadMap is designed to support health systems in early detection and management of diabetes and chronic kidney disease. It also seeks to address the social determinants of poor health in Indigenous communities, including housing quality and availability, and health infrastructure.

In 2018, Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt commissioned a report detailing how access to and outcomes of kidney transplants could be improved among Indigenous Australians. He also established a National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce to implement the recommendations from this report.

Some key recommendations include improving the communication between health-care teams, patients and their families, addressing cultural bias in the delivery of health care, and improving the quality of data around transplant access and outcomes.

Addressing transplant and treatment inequities will benefit Indigenous Australians with kidney failure sustained from ADPKD and chronic kidney disease more broadly.

Read more: To close the health gap, we need programs that work. Here are three of them

Karen Dwyer, Deputy Head, School of Medicine, Deakin University and Jaquelyne Hughes, Senior Research Fellow, Menzies School of Health Research

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.