Aspergillus at Seattle Children’s and Public Health’s role in healthcare-associated infection (HAI) response

From Public Health – Seattle & King County

Cases of Aspergillus surgical site infections acquired at Seattle Children’s are concerning to public health authorities.

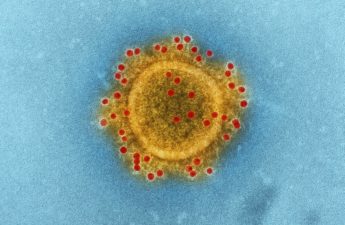

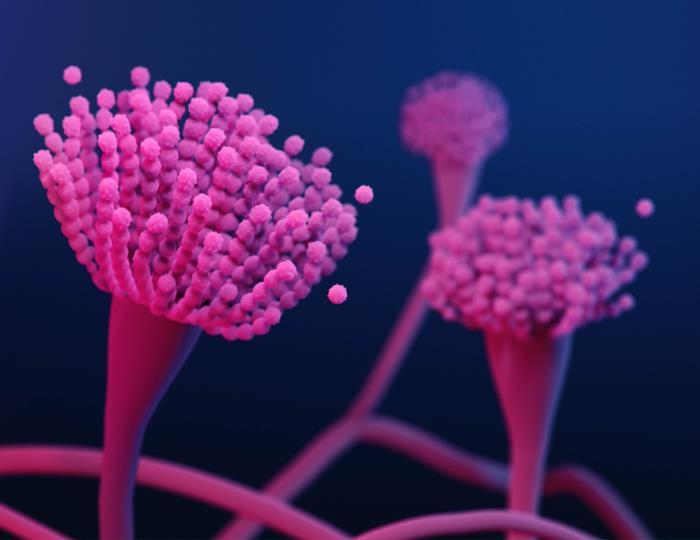

Aspergillus is a microscopic mold that is common in the environment with little impact on healthy people, but when vulnerable patients are exposed to it in the operating room setting, there is increased risk for serious infections.

Public Prevention of Aspergillus in health care environments where certain patients at high-risk of serious infection may be treated is important, yet the knowledge base of how to best address Aspergillus in air handling systems is limited.

Public Health – Seattle & King County continues to work with the Washington State Department of Health (DOH) and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) experts to understand the issue at Seattle Children’s and provide consultation on steps to address the current outbreak.

Requirements for hospitals and public health responsibilities

The Aspergillus outbreak at Children’s has prompted questions on when and how hospitals are required to notify and involve public health authorities in the response to healthcare-associated infections at their facilities.

In Washington state, health care facilities are required to report individual cases of certain notifiable diseases as well as outbreaks of healthcare-associated infections to local health departments.

Individual (sometimes called sporadic) cases of Aspergillus are not reportable in Washington state (or any other state to our knowledge). Outbreaks, which are defined as two or more cases suspected to be healthcare-associated, are reportable.

We are responsible for working with King County healthcare facilities to investigate and respond to reportable cases and outbreaks. Where appropriate, our role is to:

- Monitor for and investigate additional cases and suspected cases that are reported

- Attempt to determine whether the cases are healthcare-associated versus community-acquired

- Facilitate specialized testing through the public health laboratory system

- Identify strategies to decrease risk for further cases and support the facilities in implementing corrective actions

- Consult with authorities at DOH, CDC, and other relevant agencies and technical experts to assist in disease investigation and/or response activities as necessary

- Review data and findings of investigations and facility response plans

- Provide recommendations based on standardized guidance where available and provide additional guidance as appropriate.

- Conduct on-site infection control assessments for management of multidrug-resistant organism at long-term care facilities and provide feedback to improve infection control practices (CDC-funded project)

Public health outbreak investigations are carried out in collaboration with healthcare facilities and, at times, other agencies as noted above. Healthcare facilities are obligated by state administrative code to cooperate with public health investigations.

Regulating hospitals

Washington State Department of Health’s Health Systems Quality Assurance (HSQA) unit regulates hospitals and is responsible for ensuring overall patient safety. It is the responsibility of health care facilities to report HAI-associated hospital cases and outbreaks to HSQA, and we notify them as well.

At the local level, public health agencies do not have a regulatory or enforcement role with respect to health care facility responses to hospital-associated infections. If we have concerns that a healthcare facility is not responding appropriately to an outbreak to prevent additional cases, we communicate that to DOH HSQA and the healthcare system leadership.

Public Health involvement in Children’s response

Since Public Health – Seattle & King County was notified of new Aspergilluscases in June 2018, we have been working with Children’s on their response, in collaboration with other public health partners.

We initially connected Children’s to experts from the CDC, which has specialized knowledge in this area, and DOH to review and advise on steps that Children’s was taking to address the issue.

After the recurrence of Aspergillus cases in 2019, we again worked with CDC and DOH to review new findings, conducted a site visit and provided feedback on their mitigation strategy and any potential risk factors that might not have already been addressed. We also requested and confirmed that Children’s has an effective monitoring system to identify and report new cases rapidly.

Children’s reported the newest recurrence to us on November 10th, and we again convened experts to review the newest findings and their latest plan. Children’s decision to close 10 operating rooms to improve air systems that are the likely source of the infections is supported by Public Health – Seattle & King County.

When Public Health notifies the public:

Our priority is to ensure that ongoing risk is identified and mitigated and that Children’s notify affected patients and their health care providers, which they did.

When we think there is ongoing risk for the general public or patients and/or if affected patients can’t otherwise be identified and notified, and there is something they can do to protect their health, we will work with the hospital to ensure that the public is notified as well.

At the time Children’s had reported the new cases to us in June 2018, they had temporarily closed operating rooms where the problem was identified to investigate and address any issues that were identified, so no new patients would be exposed, and they were rapidly developing a response to prevent additional cases with input from local, state and national public health authorities.

Regarding the cases prior to 2018, individual (sporadic) Aspergillus cases are not reportable to local health departments: We were made aware in 2018 that Children’s did have previous sporadic cases and a cluster of three cases in 2004/5, which the hospital looked into.

In a publication describing their 2005 investigation, they identified contaminated dust as a potential source of the infections. In earlier discussions with Children’s and experts at CDC, we did not think that the prior cases were related to the current problem.

Only now, as we’ve continued to learn more, do we believe that the earlier cases were possibly an indicator of an ongoing problem with their air handling system.