Connor Bamford, Queen’s University Belfast

Since December 2019, there has been a cluster of 59 cases of pneumonia in Wuhan, eastern China. The pneumonia is associated with a previously unidentified coronavirus related to the deadly SARS virus.

Seven of those cases are thought to be serious, and one person – with serious pre-existing health problems – has died. The WHO has also just announced the first case outside China. A traveller from Wuhan, now in Thailand, has been confirmed by the WHO to have contracted the virus.

The World Health Organisation has urged countries around the world to enhance their surveillance of severe acute respiratory infections, although no travel restrictions have been advised. There is no licensed vaccine or specific treatments for the new virus.

The new coronavirus outbreak is linked to a market in Wuhan, which sold meat and live animals. Following the outbreak, the market was closed. There is no clear evidence of the virus spreading between humans, and it is thought that it originated in animals.

Scientists investigating the outbreak – including those from China – have reported complete virus genome sequences found in patients. The virus is not closely related to any human virus currently in circulation. So far, scientists have found evidence of the virus in 41 samples from patients with the disease.

Spectre of SARS coronavirus

The Wuhan coronavirus outbreak bears similarity to the 2002-03 epidemic of SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) coronavirus (SARS-CoV). The SARS-CoV outbreak, which started in south China, lasted for over nine months. It spread to 37 countries, causing 8,098 people to become ill and 774 to die.

Nearly 10% of those confirmed to be infected went on to die. The deadly nature of the disease, the frequent human-to-human spread, and infection of front-line clinical staff, contributed to the seriousness of the outbreak.

SARS-CoV was traced to several animals, including civet cats and raccoon dogs, being sold as food in markets. The infected animals had no symptoms. Closure of the markets with animal culling alongside treatment and containment of patients led to the outbreak being halted.

Further investigations traced SARS-like viruses to horseshoe bats found in a cave in China. It is thought that civet cats could have picked up the infection from bats and then spread it to humans in city markets.

SARS has not been seen since 2003 and it is thought that the virus is now extinct. The new Wuhan coronavirus is not the SARS-CoV, but it is similar to viruses thought to be precursors of SARS in bats.

Coronaviruses frequent species jumps

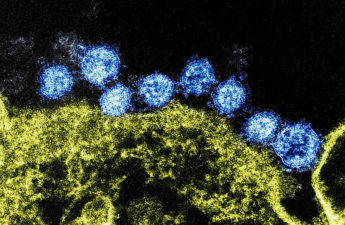

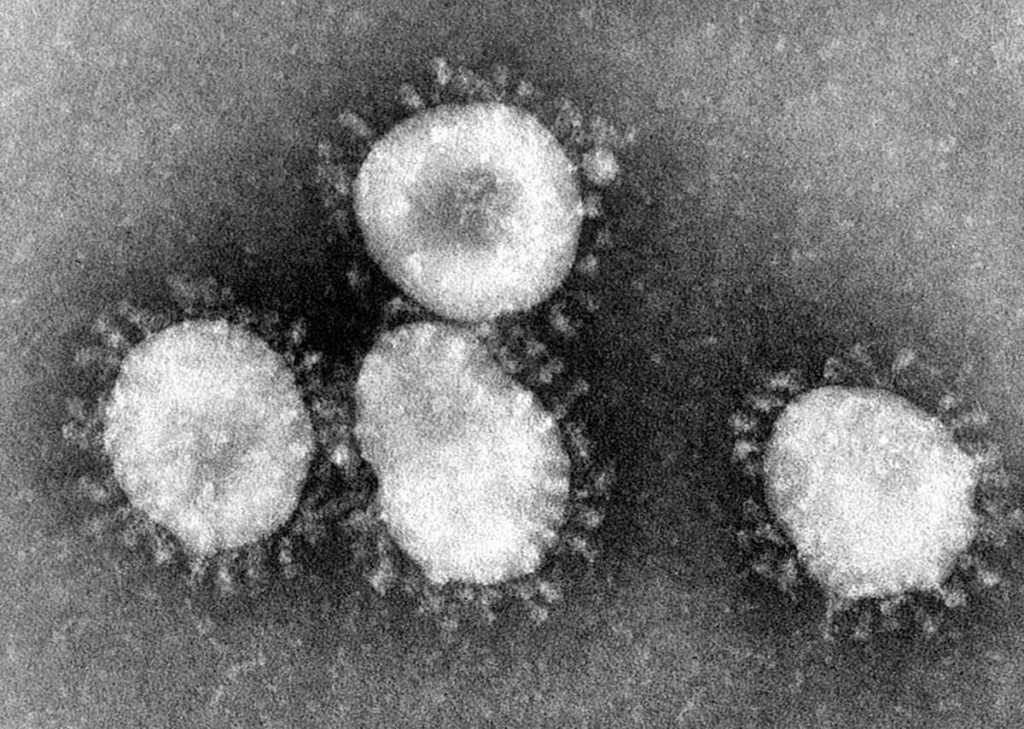

Coronaviruses are so named because of the crown-like appearance of their virus particles when seen under an electron microscope (corona, meaning crown). Coronaviruses are a diverse group of viruses that infect and cause disease in humans and other animals, including pigs and chickens.

There are seven coronaviruses known to infect people, including the novel Wuhan coronavirus and SARS-CoV already mentioned. Other human coronaviruses are those that cause the common cold like 229E, NL63, OC43 and HKU1 viruses, as well as the deadly zoonotic MERS virus.

MERS-CoV is a camel common cold virus that often jumps to humans in the Middle East. MERS-CoV can cause severe pneumonia in people and spread from person to person. MERS-CoV was only identified in 2012 and continues to be a significant problem in the Middle East. Nearly 2,500 cases of MERS have been identified, causing 858 deaths.

Coronaviruses appear to jump easily between species, and the Wuhan virus could be the third incidence in humans in the last 20 years. In 2016, another coronavirus was responsible for 24,000 pig deaths in southern China. Later named swine acute diarrhoea syndrome or SADS-CoV, it jumped from bats to pigs but did not spread to humans before it was contained.

Looking further back, close animal counterparts have been found for three of the common cold coronaviruses, suggesting zoonotic origins. Also, for SARS and MERS-CoVs it appears that an intermediate host was needed – either civet cats or camels, respectively – for this jump to be successful. The reasons why aren’t exactly clear.

Virus hunting and mass genome sequencing efforts across the world have associated much of the known coronavirus diversity to bat species. Many of these CoV-infected bats are found in south-east Asia, but other hotspots include South America, central Europe and Africa.

What we still need to know

How the new Wuhan coronavirus came to be in humans, and how closely it will resemble the SARS outbreak, will be a focus of ongoing research, such as:

1) Sequencing more virus strains to better understand their diversity and evolution. This will allow scientists to develop much needed tests and track virus spread, assessing whether human-to-human transmission is occurring.

2) Provide robust evidence that the new coronavirus is associated with pneumonia either through detailed clinical investigation or experimental assessment of causation in lab animal.

3) Find the origin of the outbreak, determining the role of bats and intermediate animal hosts in the spread of infection.

Outbreaks of new viruses, such as the Wuhan coronavirus, are a constant reminder of the need to invest in research in emerging virus biology and evolution, how they infect and interact with human cells, and ultimately, to identify safe and effective drugs to treat – or vaccines to prevent – serious disease.

Connor Bamford, Research Fellow, Virology, Queen’s University Belfast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.