By Christine Vestal, Stateline

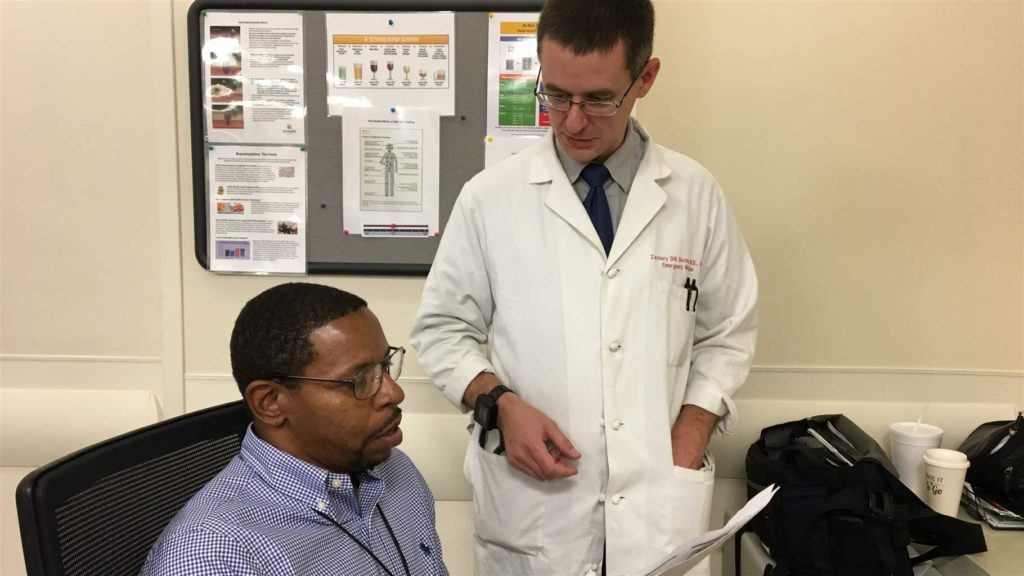

BALTIMORE — For Dr. Zachary Dezman, an emergency physician in this heroin-plagued city, there’s no question that offering addiction medicine to emergency room patients is the right thing to do.

People with a drug addiction are generally in poorer health than the rest of the population, he explained. “These patients are marginalized from the health care system. We see people every day who have nowhere else to go.

“If they need addiction medicine — and many do — why wouldn’t we give it to them in the ER? We give them medicine for every other life-threatening disease.”

But elsewhere in the country, all but a few emergency doctors and hospital administrators see things differently. They worry that offering addiction services could attract even more drug-seeking patients than they already see, taking up valuable staff time and beds, said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, co-director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University.

Instead of providing anti-addiction medication, most hospitals typically give ER patients with drug-related conditions the telephone numbers of local treatment clinics, he said.

Despite a raging drug overdose epidemic that is killing nearly 200 Americans every day and sending thousands more to emergency rooms, the vast majority of the nation’s more than 5,500 hospitals have so far avoided offering any form of addiction medicine to emergency patients.

That’s starting to change.

In Dezman’s ER at the University of Maryland Medical Center Midtown Campus in West Baltimore — and in 10 other Maryland hospitals — addiction services, including starting patients on the highly effective anti-addiction medication buprenorphine, is a new and growing emergency service.

Similar services are planned for emergency departments in 18 more Maryland hospitals, according to Marla Oros, president of Mosaic Group, a management consulting firm that is providing technical assistance to the state’s hospitals.

Approved by the FDA in 2002 for the treatment of opioid addiction, buprenorphine has been shown to be more than twice as effective as non-medication therapies at helping opioid users quit. Taken daily by mouth, the narcotic medication eliminates withdrawal symptoms and drug cravings, allowing users to feel normal without producing a high.

“We’ve learned that certain places are conducive to engaging patients in treatment. One of them is the ER. The other is the criminal justice system. We need to grab those opportunities and offer patients effective treatment when they’re ready.” — Dr. Eric Weintraub, professor of psychiatry University of Maryland School of Medicine

A 2017 study by researchers at Yale School of Medicine found that opioid-addicted patients who were given an initial dose of buprenorphine in an emergency room were twice as likely to be engaged in treatment a month later compared with those who were given only referrals to addiction treatment specialists. Lead author Gail D’Onofrio wrote in an email to Stateline that the practice is spreading.

Still, a 2017 survey by the American College of Emergency Physicians showed that only 5 percent of emergency doctors work in hospitals offering the anti-addiction medications buprenorphine or methadone, and 57 percent said that detox and addiction treatment facilities outside of the hospital were “rare or never accessible.”

Dr. Eric Weintraub, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, was an early adopter of buprenorphine in the ER and is now helping spread the concept to other hospitals.

Starting in 2003, he initiated patients on buprenorphine in the psychiatric ER at the University of Maryland Medical Center in downtown Baltimore, and said he found it very effective at allowing patients to feel normal again and start thinking about treatment.

In general, Weintraub said in an interview, “We’ve learned that certain places are conducive to engaging patients in treatment. One of them is the ER. The other is the criminal justice system. We need to grab those opportunities and offer patients effective treatment when they’re ready.”

Waiting for Patients

On a stormy Monday morning in September, the emergency room at Midtown Campus is quiet. Curtained-off patient rooms sit mostly empty and a police officer leans on a counter at the nurses’ station chatting with a doctor.

Standing nearby, Dezman glances at the automatic glass doors at the entrance and says a wave of overdose victims could start rolling in at any time.

“That’s the way it typically happens,” he said. “We’ll hear from EMS that four people were found within a two-block radius and two more were found dead nearby. It’s almost always because of a bad batch of fentanyl.

“If someone were to come in right now or at any time before 4 p.m. and need treatment, ER personnel would screen them and probably send them across the street to the hospital’s Center for Addiction Medicine.”

But outside of regular business hours when treatment facilities are typically closed, the ER staff would give willing patients their first oral dose of buprenorphine here, hold them an hour or two for observation, and make an appointment for them with a treatment center for the next morning, he explained.

Once patients take buprenorphine their mood changes almost immediately, Dezman said, and they typically are much more open to talking with a coach about follow-up treatment.

On average, about 70 people come to Midtown Campus’ ER every day, and two or more of them are here because of an overdose.

But in West Baltimore, drug use is so prevalent that the emergency department’s standard protocol is to screen everyone for drug and alcohol abuse, whether they come in for a persistent cough, a broken limb or abdominal pain.

First, a triage nurse asks questions about substances patients are using. When patients are suspected of having an addiction, caregivers take urine toxicology screens and a peer recovery coach on staff in the ER talks to patients to see if they are ready to accept treatment.

In the meantime, attending physicians and nurses take care of patients’ urgent medical needs.

Dezman has a special Drug Enforcement Administration license that allows him to prescribe buprenorphine, which is a narcotic.

Most emergency physicians don’t have a buprenorphine prescribing license, and Oros said they aren’t willing to complete the eight hours of clinical training required to get it. But under what is known as the three-day rule, doctors without a DEA license can administer a single dose of the medication to a patient within a 72-hour period.

As a result, any of the doctors on duty in the ER at Midtown Campus can begin dispensing the potentially life-saving drug and work with a recovery coach to motivate patients to go to a treatment center to get their second and subsequent daily doses. Once patients are stabilized, they can get a monthly prescription for the addiction medication from any primary care doctor who has a DEA license.

Open Windows

The success of addiction assessment and treatment in the ER depends largely on the phase of drug use or withdrawal the patient is in, and whether she is mentally ready to quit.

In overdose cases, patients typically feel physically horrible because they’ve woken up in heavy withdrawal and want to get a fix as soon as possible. “But some are ready to think about whether they want to keep doing this for the rest of their lives,” Dezman said.

Occasionally, patients will come in on their own and say they want help with their addiction, and they mean it. But it’s not usually that straightforward, explained a Midtown Campus recovery coach, Dwayne Dean. “I might suspect they’re just here for a sandwich and a nap, or to get medications to relieve their withdrawal symptoms. But it’s not for me to judge. I’ve got to catch them in that small window of time.”

Since the buprenorphine initiation program began, in July 2017, recovery coaches on duty here at Midtown Campus from 6 a.m. to 2:30 a.m. have screened and interviewed 87 percent of the patients who visit each day.

In most cases, the patients they miss are those who are critically ill and need surgery or are immediately transferred to intensive care. To ensure even more patients are screened, the hospital is hiring additional recovery coaches to follow up with critically ill patients once they are stabilized.

Breaking Barriers

In Maryland, hospital management consultant Oros says everyone from the executives to the physicians and nurses are enthusiastic about the program.

And dozens of treatment providers in the Baltimore area are participating, taking middle-of-the-night calls from ERs and opening their doors earlier than usual to accommodate patients.

“If you really want to see overdose deaths come down in the United States, getting treatment with buprenorphine has to be easier and cheaper for people with substance use disorders than getting heroin and other opioids on the street.” — Dr. Andrew Kolodny, co-director Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University

In 2016, Maryland’s drug and alcohol overdose deaths shot up two-thirds to more than 2,000. More than half of the fatalities occurred in Baltimore County. And Maryland is second only to Massachusetts in the rate of opioid-related emergency visits, according to federal-state data.

So, for Maryland hospitals, it made financial sense to help as many people as possible with their addictions so they wouldn’t have to keep showing up in their emergency departments, Oros said.

Although the stigma associated with addiction is starting to wane among the general public, Brandeis University’s Kolodny said, emergency doctors and nurses see the worst of the worst when it comes to drug users, and many don’t want anything to do with them. Hospital administrators also consider people with addiction to be poor insurance risks in states that have not expanded Medicaid, he said.

“But if this movement in Maryland and other states is successful and starts to become normalized nationwide, it could change everything,” Kolodny said.

“If you really want to see overdose deaths come down in the United States, getting treatment with buprenorphine has to be easier and cheaper for people with substance use disorders than getting heroin and other opioids on the street. And what could be easier than walking into an ER and getting started on buprenorphine?”

Hospitals That Offer Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine initiation and other addiction services are offered in:

- Baltimore at Bon Secours Hospital, Mercy Hospital, MedStar Harbor Hospital, MedStar Union Memorial, MedStar Good Samaritan, University of Maryland Medical System, University of Maryland Medical Center Midtown, Johns Hopkins Bayview and St. Agnes Hospital

- Baltimore County at MedStar Franklin Square and Greater Baltimore Medical Center

- Boston at Massachusetts General Hospital

- Brunswick, ME, at Mid Coast Hospital

- Camden, NJ, at Cooper University Health Care

- Charleston, SC, at the Medical University of South Carolina University Hospital and two other locations

- Eureka, CA, at St. Joseph Hospital

- Los Angeles at LA County and University of Southern California Medical Center, Harbor UCLA Medical Center and Olive View-UCLA Medical Center

- Marin County, CA, at Marin General Hospital

- New Haven, CT, at Yale-New Haven Hospital

- Oakland, CA at Highland Hospital

- Philadelphia at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

- Placerville, CA, at Marshall Medical Center

- Redding, CA, at Shasta Regional Medical Center

- Sacramento, CA, at UC Davis Medical Center

- San Francisco County at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, St. Mary’s Medical Center and St. Francis Memorial Hospital

- Syracuse, NY, at Upstate University Hospital

- Plus 17 other hospitals in California

Source: Stateline research