By Michael McCarthy

Children exposed to the Zika virus either in pregnancy or early in life should be monitored into adolescence for signs of subtle neurological damage — even if they appeared normal at birth, say researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine and their colleagues in an editorial published today in the scientific journal. Trends in Microbiology.

The scientists, physicians and psychologists said recent studies show that the virus can cause subtle damage to developing brains. The harm may not be immediately evident, but could have serious, long-term effects on learning and cognitive development.

“Evidence is accumulating to support referring these children to a developmental specialist for testing even if they do not show the typical signs of congenital infection,” said co-author Erin Olson, an educational psychologist at the UW who specializes neurodevelopmental disorders.

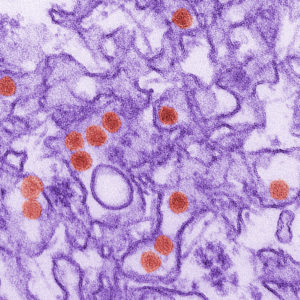

Zika virus is named after the Zika forest in Uganda where it was first identified. It is spread primarily through bites from infected mosquitos but can also be spread through sexual contact and from mother to fetus during pregnancy.

The virus was first detected in the Americas in Brazil in 2015. It rapidly spread through South and Central America, the Caribbean, Mexico and Puerto Rico with hundreds of thousands of cases reported. Local transmission was detected in the continental United States in Texas and Florida, but there have been no recent cases. The travel advisory to these states was lifted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC estimates that more than 2,400 U.S. women and nearly 5,000 women in U.S. territories and Puerto Rico were exposed to Zika during their pregnancies. Tens of thousands of pregnant women are thought to have been exposed in the rest of the Americas.

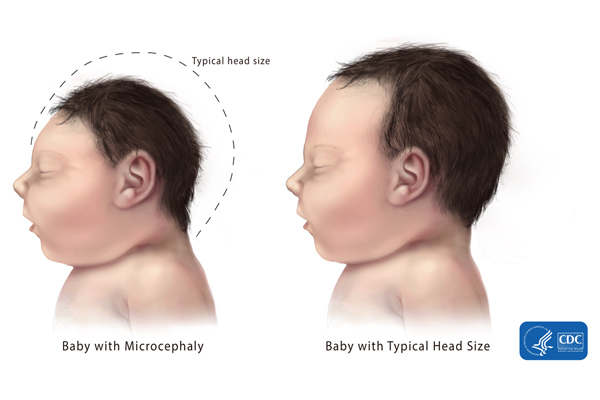

Symptoms of Zika infection include rash, conjunctivitis, headache, and joint and muscle pain. Symptoms are typically mild and last only a few days to a week. Infections of women during pregnancy, however, have resulted in severe neurological damage to the fetus, resulting in children being born with abnormally small heads, a condition called microcephaly, and other abnormalities such as eye defects and limb deformities.

“Although we haven’t heard much about Zika in the last year, the virus is still circulating in the Caribbean, Central and South America, Southeast Asia and Africa – and it remains very dangerous to pregnant women and children,” said Dr. Kristina Adams Waldorf, the commentary’s lead author and a UW professor of obstetrics and gynecology.

Currently the CDC recommends that providers caring for Zika-exposed children who don’t have microcephaly or other signs of the illness should “remain alert” to any indications that the child might have undiagnosed damage.

The authors point to their work and that of others that show Zika can damage cells in areas essential for normal brain development even when the brain appears to be normal.

Co-author Branden Nelson, a neuroscientist at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, said neural stem cells damaged by Zika virus play a key role in learning and memory.

“Normally in the late fetal brain, all the way through childhood and into adulthood, these stem cells should be actively dividing producing new brain cells, Nelson said. “In the Zika-infected brains that we studied, these cells are not making many new neurons and the neurons they make are not normal.”

Nelson and colleagues published those findings in February in the journal Nature Medicine. That project was led by Adams Waldorf and co-author Dr. Lakshmi Rajagopal, a UW associate professor of pediatrics and an expert on newborn infectious diseases at Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

Zika-related brain damage can have profound effects on a child’s development, affecting their ability to acquire crucial motor, memory and learning skills, said psychologist Olson. Subtle damage whose effects are seen later in life can be more difficult to detect, she said. They could involve neurological disorders such as seizures, epilepsy and fine motor control, and behavioral problems.

“All these children should be considered at risk and assessed regularly during the first 24 months of life. That way we can start interventions early when we know they are most effective,” she said. “And monitoring should continue into adolescence to identify higher-order neurocognitive functions, including abstract reasoning, language and mental health.”