By Michael Ollove, Stateline

A series of recent court rulings and settlements, including one last week in Indiana, have found that states cannot withhold potentially life-saving but expensive medications from Medicaid beneficiaries and prison inmates who have chronic hepatitis C.

Hepatitis C kills far more Americans than any other infectious disease. But when new antiviral drugs that for the first time promised a cure for hepatitis C hit the market in 2014, states blanched at their eye-popping prices and took steps to sharply limit the availability of those treatments for Medicaid beneficiaries and inmates. According to one recent survey, only 3 percent of inmates in state penitentiaries with hepatitis C receive the cure.

The antiviral drugs have since become cheaper, but judicial decisions and settlements have consistently found that states cannot deny treatment because of cost in any case.

In the latest ruling, U.S. District Judge Jane Magnus-Stinson, chief judge of the U.S. Southern District of Indiana, said that withholding or delaying treatment from hepatitis C-infected inmates was unconstitutional, amounting to cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment. The U.S. Constitution requires state penitentiaries to provide health care to prisoners.

The ruling follows a similar decision in Florida last year and settlements reached this year in Massachusetts and Colorado that require correctional systems in those states to provide treatment to virtually all infected inmates. Colorado has set aside $41 million over two years to treat all inmates with the virus. Similar lawsuits are pending in Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Missouri and Tennessee.

Likewise, states have been on the losing end of lawsuits involving Medicaid beneficiaries who have been denied hepatitis C treatments in Colorado, Michigan, Missouri and Washington, forcing changes in policies to make the cure more broadly available.

And settlements have been reached elsewhere, including in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Florida, according to the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation at Harvard University. States run Medicaid agencies, which provide health care to the poor, and split the costs with the federal government.

While providing the treatments will cost states tens of millions of dollars, health policy experts insist the spending will provide an overall economic and public health benefit. Attacking hepatitis C in prisoners and in Medicaid patients, they say, will go a long way toward eradicating the disease while also saving money by preventing patients with untreated hepatitis C from progressing to liver failure and cancer.

“The most important thing to remember about cost-effectiveness is that something that is really expensive can still be cost-effective if it is really, really effective,” said Mark Roberts, chairman of the University of Pittsburgh department of health policy and management who has written studies about the new hepatitis C medications. “And these drugs are very, very effective.”

A Cure Arrives

The new antivirals, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration late in 2013 and first sold the following year, represented a giant leap from previous treatments. The treatment period for the old drugs lasted as long as 48 weeks, entailed severe side effects, and delivered a cure rate lower than 50 percent.

By contrast, the new antivirals usually require 12-week treatment periods, carry virtually no side effects and boast an effective rate above 95 percent. For the estimated 3.5 million Americans with hepatitis C, the new drugs promise a pain-free cure. Hepatitis C is particularly prevalent among baby boomers, who were susceptible to the disease at a time when infection controls were less prevalent, and among drug users who share contaminated needles.

When the drugs first hit the market, a single course of treatment cost as much as $84,000.

“States were terrified by their cost exposure,” said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. “And they had no idea how many people would show up on Day One demanding the cure. Would it be 75 percent? Twenty-five percent? One percent? They had no idea what their exposure was.”

The prevalence of hepatitis C is thought to be higher among Medicaid beneficiaries than the general population, Salo said, with estimates ranging from 700,000 to 1 million Medicaid patients infected. And the rate is higher still in prisons because of illicit drug use and do-it-yourself tattooing common in penitentiaries. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1 in 3 prisoners in U.S. jails and prisons has hepatitis C.

In response to the high prices, state Medicaid agencies and prisons decided to essentially ration the new drugs.

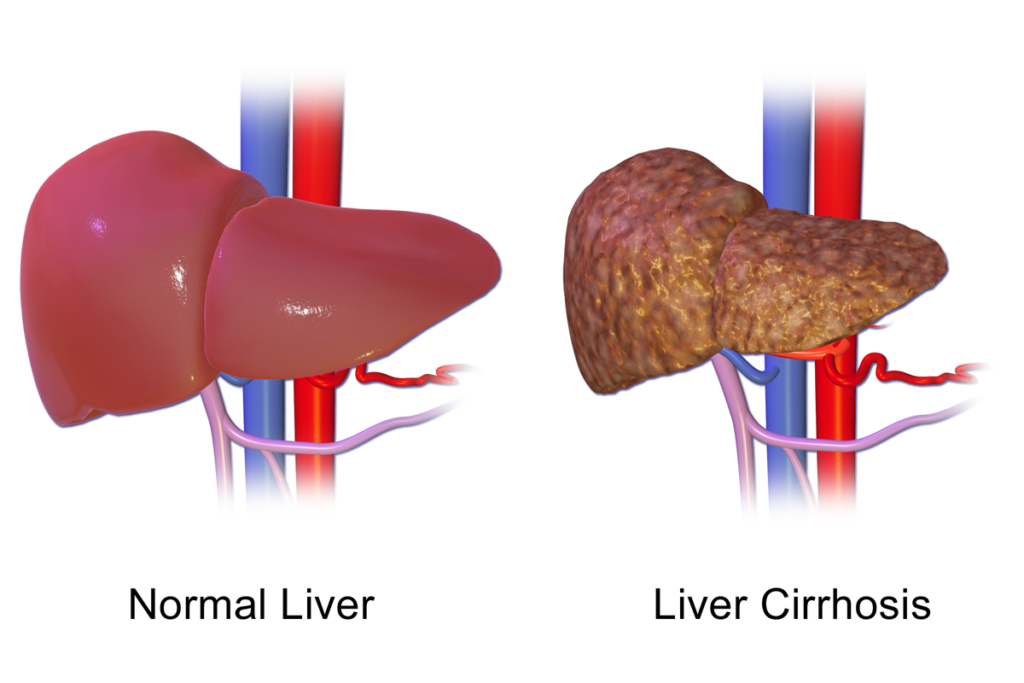

They relied on blood tests to determine the severity of a patient’s disease, measuring the level of fibrosis, or liver scarring. Patients were given scores, from F0 (no fibrosis) to F4 (cirrhosis, or late-stage scarring of the liver).

In the corrections and Medicaid systems, only patients with higher scores were eligible for treatment. Many states also denied treatment to active drug users, and in Medicaid programs, they limited the numbers of doctors who could prescribe the new antivirals.

Nationwide, at least 144,000 inmates at state prisons with hepatitis C (97 percent) aren’t getting the cure, according to a new survey by Siraphob “Randy” Thanthong-Knight at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

In Vermont, according to VTDigger, one state lawmaker called it “appalling” when he learned at a legislative hearing last week that in 2017, of 258 state prisoners with hepatitis C, only one had received the cure.

Stigma

Those restrictions drew a firestorm of criticism, not only from advocates for Medicaid beneficiaries and prisoners, but from human rights and medical organizations, such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the World Health Organization. Many argued that policymakers stigmatized patients with hepatitis C in a way they would never consider with other diseases.

“If there were a cure for breast cancer or Alzheimer’s or diabetes, people would be storming the White House to make sure those medicines were available to everyone, you can be sure of that,” said Robert Greenwald, a professor at Harvard Law School and the faculty director of the school’s Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation. “But we’ve responded completely differently with the cure for hepatitis C because of the stigma associated with that disease.”

Greenwald and others insist that treating prisoners with hepatitis C is an indispensable step toward eradicating the disease in the whole population.

Stateline contacted communication offices for a dozen state Medicaid offices that restrict hepatitis C antivirals to patients with fibrosis scores of F3 or F4. Two states, Kansas and Arkansas, responded. The Kansas Department of Health and Environment said it dropped its disease severity restriction for Medicaid beneficiaries in August. A spokeswoman for the Arkansas Department of Human Services wrote in an email: “We continue to monitor what other states are doing, and how it compares to our current policies, to identify the need for potential changes.”

In 2015, the Obama administration urged state Medicaid agencies to lift restrictions on the drugs. By 2017, at least 17 states lifted restrictions based on severity. Many others retained the restrictions but loosened them to make the drugs available to beneficiaries with less severe liver damage.

The movement in prisons has been slower, nudged along mainly by the lawsuits. “They have been slow to respond,” said Tina Broder, interim executive director of the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable, a coalition working to eradicate hepatitis B and C.

Kellie Wasko, deputy executive director at the Colorado Department of Corrections, said the settlement the state reached with the American Civil Liberties Union last month only formalized what the state had decided to do on its own, which was to treat all the estimated 2,200 Colorado prisoners with hepatitis C.

“As a health care professional, I do believe it is right to treat everybody,” said Wasko, who is a nurse.

She acknowledged that the drugs’ lower costs made the decision easier for the prison administrators and the legislators who appropriated the $41 million for treatment.

Originally, she said, the price for a single course of treatment was $56,000. Because of contract requirements, she said she couldn’t reveal the price Colorado pays now, but “it is significantly less.”

Other experts say that with discounts, Medicaid and corrections systems can now pay as little as $10,000 for a course of treatment.

“Even at those prices,” Harvard’s Greenwald said, “states are waiting for us to litigate before they’ll remove these restrictions. And the only explanation for that is the stigma.”