Victoria Knight, KHN

President Donald Trump told the American people this week that convalescent plasma is a potential new treatment for COVID-19. His announcement followed the Food and Drug Administration’s decision Sunday to grant fast-track authorization for its emergency use as a treatment for hospitalized COVID patients.

This “emergency use authorization” triggered an outcry from scientists and doctors, who said the decision was not supported by adequate clinical evidence and criticized the FDA for what many perceived as bowing to political pressure.

With all the news swirling around convalescent plasma, we thought we’d break it down for you.

1. Convalescent plasma contains antibodies against disease. Donations are being promoted as a potential COVID-19 treatment.

“Convalescent” refers to recovery from a disease. And plasma is the yellowish, liquid part of blood in which blood cells are suspended.

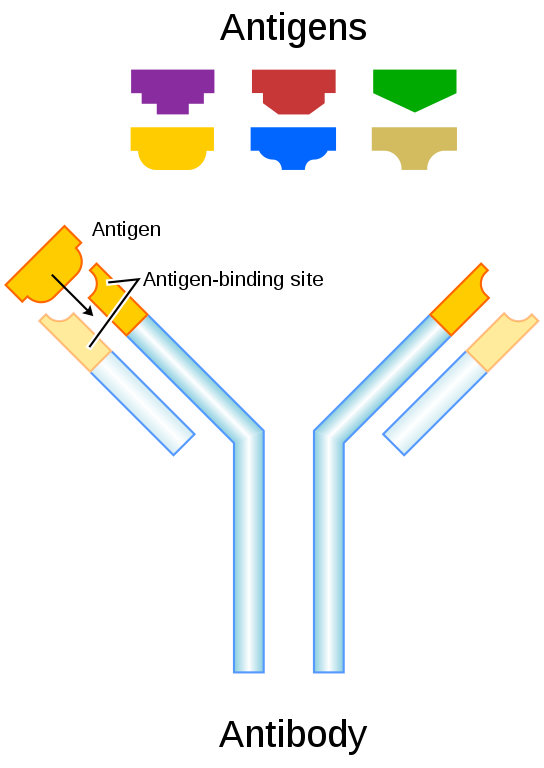

When someone is infected with a virus, the body generates antibodies to fight off the viral particles. Enter COVID-19. If an individual who has recovered from this virus donates their plasma, scientists can isolate the antibodies from the plasma and give it to patients who are still in the early stages of their COVID-19 infection. This infusion, in theory, should help people fight off the virus while their own body catches up and makes its own supply of antibodies.

It’s not a new concept. An infusion of antibodies via plasma has been used as a treatment for other types of diseases, such as rabies.

2. Some experts took issue with the data presented to approve the treatment and thought the FDA action crossed a political line.

An FDA emergency use authorization allows companies and medical providers to deploy unapproved treatments or medical products in a crisis. The FDA said health care providers would be authorized to distribute COVID convalescent plasma to treat suspected or confirmed patients with COVID-19 while in the hospital.

Before the authorization, some top researchers and clinicians at the National Institutes of Health felt there was not sufficient scientific evidence to support pushing the treatment forward.

“A randomized placebo control trial is the gold standard,” said Dr. Howard Koh, who was an assistant secretary at the Department of Health and Human Services from 2009 to 2014 under President Barack Obama. “If you don’t have that standard and don’t have some evidence from a high-quality study or [a randomized controlled trial], you are left with suboptimal science and treatments in the long run that may not prove to work.”

Koh also said that for other COVID-19 treatments including the medication remdesivir, a randomized clinical trial had been done before the FDA OK’d it for emergency use.

When the emergency authorization for convalescent plasma was announced, HHS officials pointed to findings from a Mayo Clinic preliminary analysis as the rationale. The analysis has not been reviewed by other scientists and doctors.

Suspicions of a political motive behind the decision were heightened because the authorization came one day before the start of the Republican National Convention.

“The timing raises so many questions,” said Koh, also a professor of the practice of public health leadership at Harvard University. “I think this announcement shakes the confidence of the medical community in the rigor of the FDA decision-making process.”

Trump tweeted just a day before the FDA’s action, “The deep state, or whoever, over at the FDA is making it very difficult for drug companies to get people in order to test the vaccines and therapeutics. Obviously, they are hoping to delay the answer until after November 3rd. Must focus on speed, and saving lives!”

Scott Gottlieb, a former Trump administration FDA commissioner, offered his take in a tweet the day after the announcement: “Plasma may provide a benefit, and it could be meaningful for certain patients, but we need more evidence to prove it. The data FDA had supports an authorization for emergency use, where the standard is ‘may be effective’ but we need better studies to confirm preliminary findings.”

3. Dr. Stephen Hahn, the current FDA commissioner, misrepresented the data on the treatment’s effectiveness during Sunday’s press conference. Hahn later corrected himself.

The Mayo Clinic analyzed outcomes of patients who were given a low dose of plasma and those given a high dose. Those who got the high dose had a lower seven-day mortality rate (8.9%) compared with the seven-day mortality rate of those given a low dose (13.7%).

Dr. Adam Gaffney, a critical care doctor and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, said these two variables were used to calculate what is known as a “relative risk reduction,” or the percent difference between the risk of two different treatment outcomes. In this case, the risk reduction between the high dose and low dose of plasma is 35%.

That’s the number Hahn misrepresented.

“Many of you know I was a cancer doctor before I became FDA commissioner, and a 35% improvement in survival is a pretty substantial clinical benefit,” said Hahn. “What that means is — and if the data continue to pan out — 100 people who are sick with COVID-19, 35 would have been saved because of the administration of plasma.”

But, that was an incorrect statement. Hahn had confused relative risk with absolute risk, as many members of the medical community later pointed out. Absolute risk reduction refers to the number of people who experienced reduced mortality from a treatment compared with the rest of the entire population who didn’t get the treatment. The absolute risk reduction in this situation is probably closer to 3-5 cases out of 100.

On Monday night, Hahn issued a tweet to set the record straight: “I have been criticized for remarks I made Sunday night about the benefits of convalescent plasma. The criticism is entirely justified. What I should have said better is that the data show a relative risk reduction not an absolute risk reduction.”

Hahn also noted in the Twitter thread that the agency’s decision was not political, but “made by FDA career scientists based on data submitted a few weeks ago.” He also said the approval was not final and the FDA could revoke authorization if needed.

4. President Trump referred to the use of blood plasma during the RNC, and is likely to do so throughout the remainder of his presidential campaign.

During the first night of the Republican National Convention, in a meeting with a group of first responders, Trump told a police officer who had recovered from COVID-19 that her blood was “valuable.”

“Once you’re recovered, we have the whole thing with plasma happening. That means your blood is very valuable, you know that, right?” Trump said. Vice President Mike Pence also mentioned it in his Wednesday night speech.

5. Critics of the convalescent plasma treatment say there must be randomized clinical trials to prove its effectiveness.

Koh said receiving convalescent plasma doesn’t appear to be dangerous, but a recent study in China did report that 2 in about 100 people experienced adverse events associated with the treatment.

And multiple experts said a randomized clinical trial is necessary to ensure that the mortality outcomes shown in the Mayo Clinic analysis weren’t confounded by other factors.

A randomized clinical trial would involve one group receiving a placebo and another group receiving the treatment. Who is assigned to each group would be completely random to eliminate bias.

Gaffney said he noticed that patients in the low-dose plasma group seemed to be sicker than those in the high-dose plasma group — which could have affected the Mayo Clinic’s findings.

“To ensure that the effect we see is the effect of the intervention, and not a manifestation of differences in how sick the two groups are,” the trial has to be randomized, said Gaffney.

The Mayo Clinic analysis also reported that some patients who received plasma also took remdesivir or steroids, which could have influenced their mortality outcomes.

Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, said, at best, he sees the outcomes of this analysis as a hypothesis that needs to be tested in a randomized clinical trial. “No survival benefit has been proven,” he wrote in an email.