Jean-Étienne Liotard/Wikimedia Commons

Tom Solomon, University of Liverpool

The remarkable progress with immunisation against COVID-19 has focused the world’s attention on the brilliance of vaccines. Many people know the story of Edward Jenner’s discovery of vaccination against smallpox in Gloucestershire nearly 250 years ago. But far fewer have heard of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.

She was the socialite whose pioneering inoculation experiments laid the groundwork for Jenner’s discovery, but whose contribution is all but forgotten. This year, the 300th anniversary of her extraordinary human experiments, provides a timely occasion to review her amazing contribution to public health.

Born Mary Pierrepont in 1689, she was a vivacious and headstrong woman who wrote poems and letters and held progressive views on women’s role in society. To avoid an arranged marriage, she eloped at the age of 23 and wedded Edward Wortley Montagu, grandson of the first Earl of Sandwich.

In 1716, Edward became England’s ambassador to Istanbul (or Constantinople as it was then), capital of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. From there Wortley Montagu wrote vivid descriptions of oriental life, especially the Turkish women, whose dress, lifestyle and traditions intrigued her. Most notable among these was their method of inoculation against the dreaded smallpox.

It had long been recognised that people could only get this disease once. If they survived, they were immune for the rest of their lives. Rather than take their chances with a natural infection and its high fatality rate, the older Turkish women sought to induce a mild case in children by “ingrafting” as they called it.

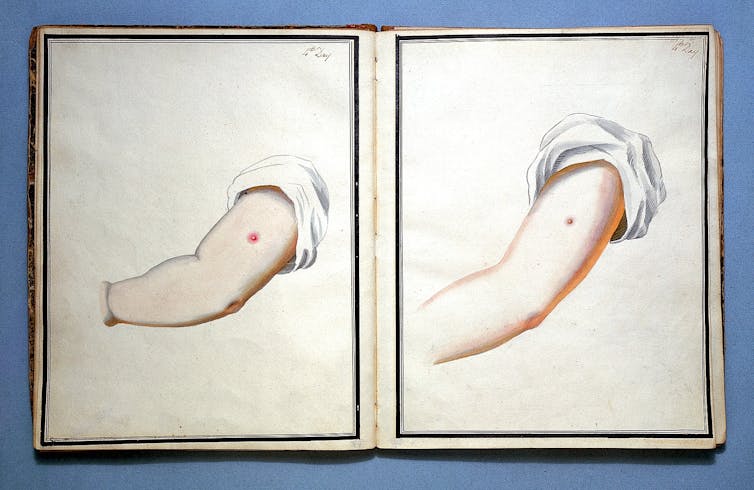

Smallpox causes blisters and scabs on the skin of those afflicted by the disease. The women would take the pus from one patient’s blister and scratch it into a cut they would make on the arm of the person they wanted to protect. This would usually lead to mild symptoms, followed by lifelong protection.

“There is a set of old women [here],” Wortley Montagu wrote, “who make it their business to perform the operation, every autumn … thousands undergo this … [and there] is not one example of anyone that has died in it.”

Wortley Montagu herself had survived smallpox but was left with facial scarring. Her brother had succumbed to the illness. She was keen to protect her young son from the disease and convinced the embassy surgeon to inoculate him.

“The Boy was engrafted last Tuesday,” she wrote in a letter to her husband, “and is at this time singing and playing, and very impatient for his supper.”

Wortley Montagu was determined to “bring this useful invention into fashion in England”.

Within a couple of years, she had returned home. In 1721, there was a smallpox epidemic, and Wortley Montagu asked the embassy doctor, who had come to London with her, to engraft her young daughter who had not been inoculated.

Nervous for his reputation, the doctor asked several medical witnesses to observe the procedure. In April 1721, he inoculated young Mary Alice, the first time the procedure was performed in Britain. Although the observers were impressed, others were sceptical about this dangerous, exotic practice. Wortley Montagu and her daughter visited households affected by smallpox to demonstrate that she was protected. However, many doctors remained cautious. Wasn’t this a risky procedure? What if it caused severe or fatal disease?

Death or inoculation

In August 1721, an extraordinary experiment was performed at London’s Newgate Prison that helped persuade people of the benefit of smallpox inoculation. Several prisoners awaiting execution were offered the chance to have inoculation with smallpox instead – being allowed their freedom if they survived. All took the offer and lived to tell the tale. To prove the immunisation actually protected against disease, one of the female prisoners was sent to nurse a young boy with smallpox, sleeping with him every night for six weeks without becoming unwell.

Although inoculation remained a controversial practice, with some medical and religious opposition, this prison experiment strengthened considerably the campaign for “variolation”, as the procedure is now known. Wortley Montagu’s friend, the Princess of Wales, was convinced and had her own children inoculated. Royalty across Europe followed suit, as did the wealthy of New England, where smallpox was raging.

Wellcome Library/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Even though severe disease occasionally occurred after inoculation, and was sometimes fatal, the procedure saved thousands of lives. Wortley Montagu’s contribution was celebrated by French poet Voltaire among others, and inoculation became a rallying point for the enlightenment.

Seventy-five years later, English physician Dr Edward Jenner, who had been inoculated as a child, took the process one step further. He realised those who had suffered from cowpox, a related disease of cattle that is very mild in humans, were subsequently immune to smallpox. Jenner therefore jabbed people with cowpox material and then proved this was effective against smallpox by injecting them with smallpox using Wortley Montagu’s variolation approach.

Vaccination, as the Jenner procedure became known after the Latin vacca for cow, proved to be safe and was subsequently taken up globally. Jenner received many honours and awards, and the work led to the eventual eradication of smallpox in 1976.

Every medical student around the world now learns about Jenner; his portrait hangs in the Royal College of Physicians of London. Even Blossom, the cow who provided the original cowpox material for Jenner’s experiment, is remembered. Her hide sits in St George’s Hospital Medical School, and her portrait hangs in the Royal College of Pathologists. But Wortley Montagu, whose pioneering efforts laid the groundwork for Jenner’s experiments, is forgotten. Whether her work would be remembered had she been a gentleman physician, rather than a lady socialite, can only be guessed at. Now, 300 years later, the Royal College of Physicians of London is looking into the most appropriate way to recognise her contribution.

Tom Solomon, Director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Protection Research Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections, and Professor of Neurology, University of Liverpool, University of Liverpool

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.