By Michael Ollove, Stateline

By Michael Ollove, StatelineThe hope is that new ways of collecting and analyzing data identified during the project eventually will spread to all states.

The $880,000, three-year U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention effort in Colorado, Hawaii, Kentucky, Montana and New Mexico faces numerous obstacles, including privacy and technological issues.

But public health officials are optimistic that immunization registries, which are already operational to various extents in all states except New Hampshire — which is in the process of launching one — can help reduce the disparities in vaccination rates based on income, geography and race or ethnicity.

Officials would like to not only identify patients who are due for vaccinations, but also to reveal population groups whose immunization rates could be improved using targeted campaigns.

The project aims to do that with children and pregnant women in Medicaid. And the techniques it reveals may enable registries to be used as a tool to ensure that all Americans are up to date in their vaccinations.

To achieve that, however, states need to develop a network of digital systems capable of better communicating with each other so that a state immunization information system can receive immunization data from anyone who administers vaccines — clinicians, retail health clinics, hospitals, pharmacies, even schools — and across multiple payers, such as insurance carriers and Medicaid.

“There’s so much opportunity for information to be in too many different places and never aggregated,” said Jill Rosenthal, a senior program director at the National Academy for State Health Policy, which is providing technical and policy support to the project.

A child, for instance, could receive a vaccination at school or a retail clinic, and the child’s doctor would have no way of knowing. The result, Rosenthal said, is that medical providers are left with gaps in information about which vaccinations patients have received.

Twenty percent of children have been to more than one health care provider by the age of 2, federal data shows, resulting in scattered medical records.

Immunization Disparities

U.S. immunization rates for recommended vaccines remain high, but statistics show that disparities persist between rates of young children on Medicaid and kids with private insurance. The rates are lower still among children without insurance.

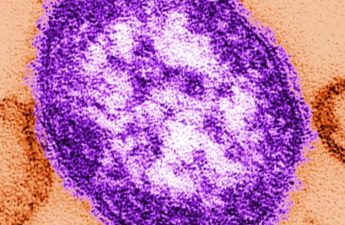

The disparities exist across different types of recommended vaccinations, including those for polio; diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis (known as DTaP); measles, mumps and rubella (MMR); and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV).

For example, among children 19 to 35 months old, the immunization rate for rotavirus — a leading cause of diarrhea in infants and children that can lead to hospitalization and even death — is 69 percent for kids in Medicaid programs compared with 81 percent for those covered by private insurance.

The disparity is also large for pregnant women. In the 2016 to 2017 flu season, 48 percent of expectant mothers on public insurance (almost always Medicaid) got the flu vaccine compared with 59 percent for private and military insurance.

The five-state project is focused on improving immunization rates for children and pregnant women in Medicaid.

The project aims to connect Medicaid information systems with their state’s immunization registries in a way that will ultimately lead to increases in immunization rates among the target population. The hope is to reveal methods that will be useful beyond these populations.

The federal funding goes not directly to the states but to the consultants — the National Academy for State Health Policy and Academy Health, a health services resource center — working with them to increase immunization rates in the targeted populations.

Rosenthal, with the health policy group, said each state will set its own priorities but that the funds will generally be used to align Medicaid and immunization information system to identify immunization gaps and to improve vaccination rates.

Officials also hope to eventually identify systemic reasons for immunization gaps: Are providers in an area not up to date on current immunization recommendations? Is there insufficient access to vaccines in certain geographic areas? Are there opportunities for targeted educational campaigns?

The exchange of information between the data systems is particularly important for reaching pregnant women. “If a woman were pregnant, we wouldn’t know it” through our system, said Bekki Wehner, Montana’s immunization program manager. “With a partnership with Medicaid, we will be able to identify that population and create an immunization strategy for them.”

Reporting Gaps

States first started immunization registries in the late 1980s, although in the early days they were localized to cities or counties. California, for example, had at least nine different registries covering different parts of the state, according to Robert Schechter, a medical officer with the California Department of Public Health.

The registries, which are confidential, then were mainly intended to track immunizations among children. Only in the last decade or so have the registries broadened to include everyone.

They have faced myriad challenges along the way. Although many providers keep electronic records, not all do, said Jan Hicks-Thomson, a public health analyst with the CDC’s immunization information system support branch. And not all have systems capable of transferring records to registries.

A bigger obstacle is that few states require providers to report immunizations. Twenty-two states do not have mandatory reporting requirements, a 2015 study in the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice found. Some states, including Montana, require parental permission before practitioners can share immunization information on children. Nevertheless, Wehner said Montana’s registry has immunization records on 97 percent of toddlers in the state.

Another complication is a federal education confidentiality law that prevents many school-based health clinics from sharing immunization records with outside agencies. (A public health exemption from HIPAA, the federal health privacy protection act, allows other medical providers to share vaccination information with registries.)

CDC guidelines for immunization registries recommend that the information collected be kept confidential. State laws establishing registries lay out information-sharing and privacy requirements.

Getting providers to collect sufficient information also can be problematic. Registries can be used for demographic analysis, such as, for example, studying immunization by race and ethnicity. But, to do so, officials need clinicians to collect and submit that information. “Often, providers don’t capture that information,” Hicks-Thomson said.

Despite the gaps, however, supporters tout the registries for contributing to the generally high immunization rates in the country. Many of the systems include a “remind and recall” function that alerts providers about patients who are due to receive immunizations, so their offices can contact those patients.

Systems also often can provide data to practitioners so they can evaluate their compliance on vaccinations. Officials can also make projections to assure that their state has sufficient dosages on hand.

While the project is geared toward a subset of Medicaid beneficiaries, Rebecca Coyle, executive director of the American Immunization Registry Association, which is also providing technical support to the project, will identify policies and data manipulation that will help immunization registries across the country maximize the systems to achieve even higher immunization rates for all.

“What we’re going to be able to do, the sky’s the limit,” she said.

Stateline is a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of the Pew Center on the States that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.