Annette Regan, University of San Francisco

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the world’s first vaccine to prevent the respiratory infection RSV, short for respiratory syncytial virus, on May 3, 2023. The new shot represents six decades of starts and stops in the hunt for a vaccine to curb one of the most common winter respiratory viruses. RSV leads to around 14,000 deaths in older adults every year and can cause severe illness in infants and children as well.

The vaccine, called Arexvy, made by the biopharmaceutical company GSK, is approved for use in adults ages 60 and over. Now that it is FDA-approved, it must still be endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a move that’s expected in summer 2023.

The Conversation asked Annette Regan, an epidemiologist and vaccine specialist, to discuss the significance of the first vaccine against RSV and the other RSV vaccine candidates that are in the pipeline.

1. How does the new vaccine protect against the virus?

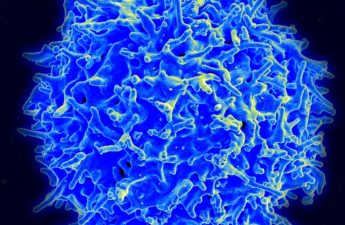

The vaccine targets a protein known as RSV F glycoprotein, which is found on the surface of the virus. The F protein enables the RSV virus to enter host cells.

By stimulating antibodies against this protein, the vaccine should protect against infection. Clinical trial data suggests this is the case, since Arexvy was 80% effective at protecting against RSV-related disease and 94% effective at protecting against severe disease.

The vaccine also includes an adjuvant, a substance that helps amplify the effect of the vaccine by boosting the immune system’s response.

2. When and for whom will it be available?

The RSV vaccine has been developed for and tested in adults age 60 and older. While the FDA has approved the vaccine – which means it has deemed it safe and effective – the shot will not be administered by health care professionals until it is reviewed by an independent expert group coordinated by the CDC called the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice, which makes vaccine recommendations to the CDC.

The committee’s recommendations will cover how the vaccine should be used – including the ages at which the vaccine should be given – the number of doses needed, the time between doses and precautions and contraindications.

The committee is expected to meet in June 2023 to make a recommendation on the new RSV vaccine, after which the CDC would officially endorse it. The vaccine could be rolled out to the public as soon as late summer 2023, well before the typical RSV season, which usually starts in the fall and peaks in winter.

It’s hard to say what the committee’s recommendation will be. It could recommend the vaccine for all adults 60 and older, or a subset of older adults. While the clinical trial showed the vaccine was 81% effective among adults ages 60 to 69 and 94% effective among adults ages 70 to 79, it was only 34% effective among adults 80 and older. Given the lower efficacy for adults ages 80 and older, the committee could place an age cap on the recommendations.

3. Why has the first RSV vaccine been so long in coming?

A vaccine against RSV has been in the works for decades. One problem that has plagued vaccine manufacturers is the difficulty of identifying an antigen – the piece of the virus that the vaccine targets – that doesn’t change, or shape-shift. The F protein of the RSV virus is notorious for changing its shape once it fuses with a host’s cell.

In 2013 and 2014, the National Institutes of Health worked out how to “freeze” the F protein into a fixed shape before fusing with a cell so that a vaccine could target it well. This was a game-changer that allowed the development of effective vaccines using this target.

In addition to challenges in identifying a good antigen, there were earlier setbacks. Early attempts to create an inactivated RSV vaccine in the 1960s were stalled after they caused an enhanced form of RSV disease. Children who had never had RSV before and received the vaccine experienced very severe illness when they encountered the virus in the community, and two children died. This tragic outcome sidetracked vaccine development for decades, as researchers needed to investigate the cause and ensure that the problem wouldn’t occur again for future vaccines.

4. What other RSV vaccine candidates are coming down the line?

In addition to Arexvy, many other promising RSV candidates are under development, some of which are likely to become available later this year or in early 2024.

The next RSV vaccine under review with the FDA is Pfizer’s RSV vaccine. It is similar to the recently approved vaccine except that it has no adjuvant and is bivalent, meaning that it targets both RSV A and RSV B – the two strains of RSV. This vaccine is meant not only for adults ages 60 and older, but also for pregnant people – with the aim of protecting young infants through maternal antibodies.

Data from a phase 3 clinical trial – the last stage of clinical trials before a company would apply for a license – shows that when given during pregnancy, the Pfizer vaccine was 82% effective in protecting infants less than 3 months old against severe RSV infection. The FDA will be making a determination on the Pfizer vaccine for older adults later in May 2023 and for pregnant people in August 2023. The CDC advisory committee is scheduled to discuss vaccine recommendations in October 2023, making this the likely next possible vaccine available.

A few other biopharmaceutical companies have developed alternative RSV vaccines, some of which are in phase 3 clinical trials. For example, Moderna has an mRNA vaccine against RSV with promising preliminary results. Regardless of which companies make it to the finish line next, it is clear that in the near future there will be a variety of new tools to help protect against RSV infection.

Annette Regan, Associate Professor of Epidemiology, University of San Francisco

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.