Experts: Mainstream Addiction Treatment Act Removes a Roadblock to Recovery

By Taylor Sisk, The Daily Yonder

August 16, 2023

When it was announced in January that restrictions were being lifted on health care providers’ ability to prescribe buprenorphine – considered the gold standard of treatment for opioid use disorder – the nation’s drug czar, Dr. Rahul Gupta, said the consequences “will be felt for years to come.”

“It is a true historic change that, frankly, I could only dream of being possible,” Gupta said.

Certainly, the announcement of the passage of the Mainstream Addiction Treatment, or MAT, Act, removing what was known as the X-waiver requirement, was good news for the three million people in this country with opioid use disorder.

Previously, providers were required to complete training and apply for a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to prescribe buprenorphine. Now, those with a current DEA registration that includes Schedule III authority can prescribe it.

“We want more people to be able to get prescriptions for buprenorphine; we know that it reduces overdose deaths,” said Dr. Bayla Ostrach. Ostrach is a medical anthropologist with Fruit of Labor Action Research & Technical Assistance, a harm reduction and rural health contracting company based in Western North Carolina. “We know that it’s evidence-based; we know that it’s more important than ever with fentanyl and xylazine in the drug supply. We want more buprenorphine prescriptions.”

Dr. Blake Fagan, director of opioid treatment services for the Mountain Area Health Education Center’s family health centers, fully agrees that the passage of the MAT Act comes as great news. A longtime advocate for the lifting of the X-waiver, he was invited to the White House for the signing of the act.

Fagan said that while there have been some 130,000 providers across the country authorized to write a prescription for buprenorphine, there will now be more than 1.8 million.

But the extent to which the MAT Act will make a difference in practice in rural communities remains to be seen. Ostrach, Fagan, and others who know rural health care and addiction treatment well stress that a lot of education will be required.

The Mountain Area Health Education Center, or MAHEC, trains residents in rural medicine in hopes they’ll choose to launch their careers in the remote communities of Western North Carolina. Fagan’s ambition is that this new generation of rural practitioners will consider a full range of treatment for substance use disorder, in office and through referrals, as being integral to their practice.

In North Carolina, an investment has been made in training medical residents and other advanced-practice providers in medication for opioid use disorder, and the results have been encouraging.

Crucial Cooperation

Equally critical to the success of the MAT Act are pharmacists.

In a recent paper for the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, Ostrach and their colleagues write that, “If prescribing increases but is not matched by increased dispensing, bottlenecks may worsen. Any worsening of buprenorphine bottlenecks could have a disproportionate impact in rural areas where residents may rely on fewer pharmacies to fill prescriptions.”

“More supports should be offered to community pharmacies by state pharmacy boards and associations,” the researchers write, “including continuing pharmacy education and technical assistance for advocating with wholesalers to increase buprenorphine order sizes, and to more effectively communicate with prescribers.”

Education and support for all parties involved, experts say, must be a grassroots effort.

‘Knock Down the Stigma’

Among the young practitioners who are advancing the use of medication for opioid use disorder in rural communities is Dr. Travis Williams. Williams trained with MAHEC and is now entering practice with Chatuge Family Practice in remote Clay County, North Carolina, two hours west of Asheville. He hopes to help foster an “ecosystem” of addiction treatment.

It took one visit to sell Williams and his wife, Liz Doyle, an emergency room nurse, on Clay County. On that first drive through Hayesville, the county seat, “We were like, ‘We’ve got to live here. This place is incredible,’” he said. “It looked like Mayberry and all the people were super nice.”

Williams soon learned that treatment options for substance use disorder in Clay County are somewhat limited. But, he said, “I think there’s a heightened sense of urgency and awareness now, not only because of the rise of fentanyl but also the fact that opioid settlement money is coming” and decisions are being made on how to allocate it.

A barrier Williams has encountered is that only one pharmacy in the county has expressed willingness to prescribe buprenorphine.

Resistance among pharmacists is a widespread issue. Research Ostrach and their colleagues conducted found that 62%of community pharmacists surveyed had refused to fill a buprenorphine prescription.

Lifting the X-waiver requirement doesn’t automatically mean a pharmacist is going to be comfortable dispensing to someone they don’t know, Ostrach said, or with filling a prescription from a prescriber they’re unfamiliar with.

“That’s not how it should be,” they said, “but it is the reality.”

Ostrach said North Carolina’s pharmacist association has been proactive in providing guidance on the specifics of the act, and that it does appear recent pharmacy school graduates are more willing than their predecessors to dispense buprenorphine.

Williams recognizes he must also address reluctance among his healthcare practitioner colleagues. Countering that reluctance, Fagan said, requires a hands-on approach.

“You have to give people time to ask their questions,” Fagan said, such as, “Are there going to be people throwing up in our waiting room because they’re withdrawing?” or, “Will there be needles all over the parking lot?”

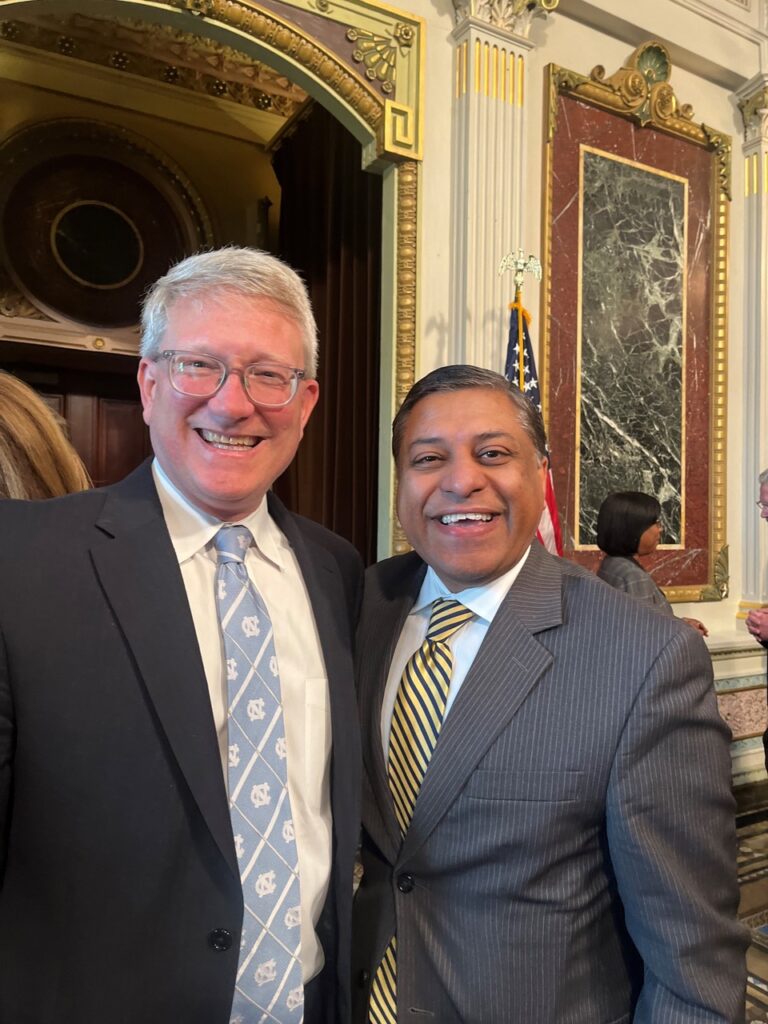

Dr. Blake Fagan, director of opioid treatment services for Asheville-based MAHEC, was invited to the White House for the signing of the MAT Act. He’s pictured here (left) with Dr. Rahul Gupta, the nation’s drug czar. (Photo provided by the Mountain Area Health Education Center)

“All of which isn’t true,” he said. “But you have to let them say all those things and get it out, and then tell them the real deal. Tell them stories about people in rural areas that have actually had their lives stabilized, or they’ve gotten their kids back from foster care.”

“You have to answer all their questions,” Fagan said. “You have to knock down the stigma.”

‘Following Their Lead’

Another concern is for the shortage of behavioral health services in rural areas that ideally complement medication for opioid use disorder.

North Carolina’s Medicaid program previously stipulated that for buprenorphine to be covered, recipients had to be receiving behavioral health care.

“I would never want to go back to a point where somebody has to have a behavioral health appointment in order to get a buprenorphine prescription,” Ostrach said.

“Meeting people where they’re at” – a term commonly used in treatment for addiction – sometimes means “following their lead,” Ostrach said. “When a person says, ‘I’m really interested in buprenorphine,’ or, ‘You mentioned there’s a [medication for opioid disorder] program,’ you’ve got to stay there with them. If you immediately jump in and say, ‘Oh, well, are you also interested in behavioral health?’ that can be a lot for somebody to think about all at once.”

Fagan agrees. While a staunch proponent of therapy to complement the medication, “I’m not one of these folks that says, ‘If you don’t do behavioral health, I’m not going to give you bupe.’ I don’t do that. You need bupe. It’s going to save your life.” Then, in a month or two, “‘You’re looking for a job? Great. Are you ready for behavioral health?’”

Williams intends to model an integrated approach to addiction treatment: “You’re their primary care physician, and you also happen to treat them for a substance use disorder, just like you’re treating them for any other chronic disorder – hypertension, diabetes, etc.”

Meanwhile, he’s building collaborative relationships with a peer recovery support specialist and a prevention specialist. He’s working to bring more pharmacies on board.

MAHEC, he suggests, could send medical students or residents to Clay County to train and provide support. Western Carolina University has a master’s of social work program and the local community college has an addiction-counseling program – all potential allies.

It’s about building an addiction prevention ecosystem, Williams stressed. “If all these things are working together, you then have a stepping stone to say, okay, what do we do about their transportation, what do we do about their housing, how do we get them a job?”

His initial conversations with county officials and other community leaders have gone well. He’s encouraged.

Facilitating medication in treatment is a critical step on the path to building that ecosystem.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.